Colourful carpets to celebrate Corpus Christi in France

At dawn, the men, women and children and members of the association join to set up the station altars and mark the 1.6-kilometre procession route through the village streets with sawdust and flower decorations.

Corpus Christi, also known as Feast of the Blessed Sacrament, is a Catholic (and sometimes Anglican) festival to honour the real presence of Christ in the consecrated wafer and wine during the communion. It is said that in 1208, a nun from the city of Liege in Belgium, named Julienne de Cornillon, had a vision of a moon in splendour with a tear in it. This recurring vision confused her because she did not understand its meaning, until Christ explained to her that the moon symbolised the Church and the tear, the absence of a Blessed Sacrament feast in the Christian calendar. Thus, in 1246, the bishop of Liège established the celebration in his diocese, but it remained a regional peculiarity for a long time until the beginning of the 14th century when Pope John XXII introduced it throughout the Church. According to the papal bull, Corpus Christi was to be a joyful and reverential celebration of the Eucharist accompanied by a procession and songs. The body of Christ was materialised in the form of a wafer placed in a glass lunula and set in a piece of silverware called a monstrance.

The love of Christ who gives himself as food remains at the heart of the worship even if the solar character of Corpus Christi probably comes from earlier cults. Celebrated sixty days after Easter, Corpus Christi is prepared well in advance. Until a few years ago, towns and villages were transformed on Corpus Christi. Strewn flowers and leaves or coloured sawdust marked the path of the procession or the station altars.

Several days in advance, families would collect flower petals from the fields, picked flowers from the garden to make the bouquets for the station altars and the floral carpets, and saved coffee grounds to outline the images.

Simone Morgenthaler gives us a colourful description of the Corpus Christi of her childhood, called "Liewerherrgottsdaa" in Alsatian: "As a child, I remember that my village was decorated with flowers and garlands on this day. Temporary altars were set up in various places and the hammer blows resounded into the night before. We went to the meadows to gather scabiosa, knapweed, lady's smock, Rhinanthus and other meadow flowers to make bouquets to be placed at the procession stops. Mother collected peonies, seringa, roses, and Virginia mayflies and arranged them in azure glass vases on the windowsills. She added an ethereal effect with Spärigelkrüt, a vaporous bush that grows from unharvested asparagus and rises like a misty mass of dotted green berries that later turn red."

Corpus Christi in Burnhaupt-le-Haut village

This religious festival during which the holy spirit is carried around to be worshipped by devotees has almost disappeared in France since the 1970s and 1980s. However, this tradition continues in a minimal form in some regions and with particular fervour in Burnhaupt-le-Haut, a village in the Upper Rhine region in France. A group of volunteers, under the guidance of Christophe Schulz, the president of the association called "Renouons avec les Traditions" (Let us renew with the Traditions) has been celebrating Corpus Christi with great enthusiasm for more than twenty years. After a two-year interruption due to the pandemic-imposed restrictions, the culmination of several months of preparation to welcome God among his devotees was seen on Sunday June 19. On Saturday, a day before the event, the flowers donated by garden centres, had been distributed to the families for the planned decorations. The plants had to be sorted and kept under a cool atmosphere as the frequent heat waves had taken a toll on field and garden flowers.

At dawn, the men, women and children and members of the association joined to set up the station altars and mark the 1.6-kilometre procession route through the village streets with sawdust.

Year after year, the volunteers have improved the decoration techniques using large stencils or a machine to spread the sawdust evenly thanks to the talent of an engineer. Rulers and sticks are used to centre the path, while a quad bike with a trailer distributes coloured sawdust, freshly mown grass, and coffee grounds at regular intervals.

Flowers emerge from the darkness of the barns and are transformed by the women into bouquets that embellish the walls around houses or enhance the altars of the four-themed stations. Religious designs made with stencils or freehand punctuate the procession route.

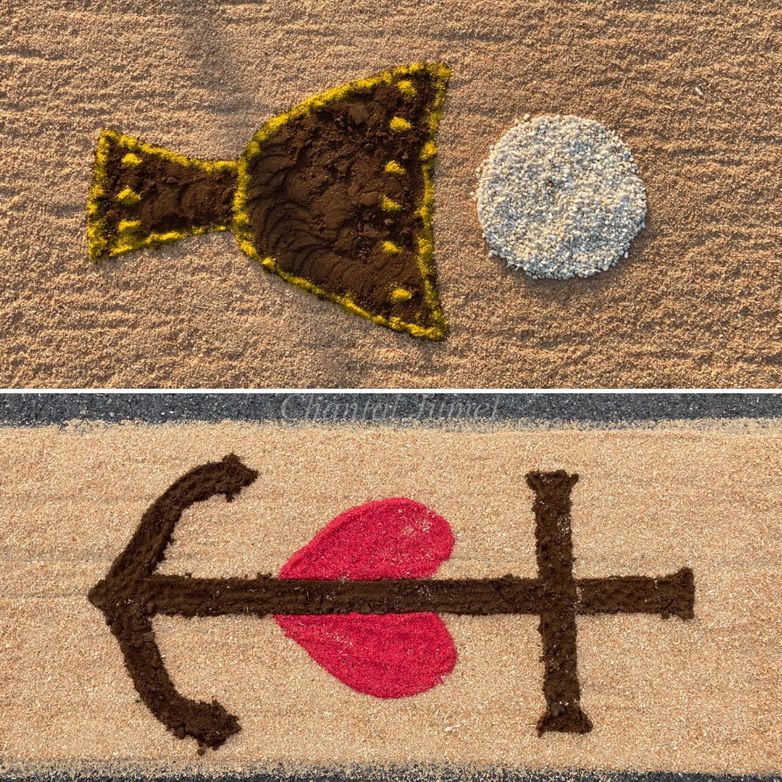

They include symbols of Christianity: a ciborium, a chalice, a dove, grapes as an image of spiritual rebirth and salvation in Christ, an anchor, the cross and a heart in one design. This spiritual dimension of the drawings made on the floor is reminiscent of certain South Indian traditions where the painted prayers reflect a subtle combination between decoration and statement of faith.

Walking with the Lord

Early in the morning, a mischievous wind scattered the sawdust here and there, but all the eyes were on the procession crossing the church porch by then. Preceded by the banner bearers, the musicians of the Soultzmatt instrumental band, the parish choir, and the children who scattered flowers along the route, the canopy appeared like another heaven, sheltering the priest in a golden mantle, and carrying the monstrance like a sun. The procession gradually reached the first altar called "O Christ, Fountain of Life". At the crossroads of two streets, the place has been transformed into a pond created from scratch with blue-coloured sawdust and various plants around a temporary altar. It was a moment of prayer, song and meditation before the procession moved on to the next altar and completed a loop, symbolising a sublimated Earth, adorned with flowers and scents that speak to the soul.