Kerala Kolam, "The Women artists of Nurani"

The doors of the sanctuary open and the priest pays homage to the divine image. In the soft glow of the oil lamps, as the devotees melt into prayer, the kolam, like visual hymns, captivate hearts in silence.

After spending four days in the village of my hosts, I am on my way to the temple of Sree Sastha, in the Nurani area of Palghat (Palakkad). Today, I have an appointment with Kavitha Girish, a valuable contact with whom I have been in constant touch throughout the pandemic. Her availability and expertise have undoubtedly enriched our discussions. Furthermore, I am also very much looking forward to meeting the women in her circle who draw kolam every day, a tradition that is devoutly observed in this temple for 41 days every year. Kavitha and her family reside in an agraharam, a traditional neighbourhood typical of villages in southern India.

Agraharam are characterised by houses lined up along straight streets, often with a temple dedicated to a local deity in the centre or nearby. In these neighbourhoods, traditions and rituals have been carefully maintained for centuries by Tamil Brahmins, a priestly class that includes priests, scholars, grammarians, lawyers, and temple cooks.

Most of Nurani’s inhabitants of are Iyer Brahmins, followers of the Advaita Vedanta philosophy initiated by the spiritual master and religious reformer Adi Shankara in the eighth century. The migration of Tamil Brahmins from Tanjore (Thanjavur) in Tamil Nadu to Palakkad dates back dates back to the eight century AD, during the reign of the Chera and Pandya kings. According to some accounts, King Rajashekhara Varman brought ten families of Tamil Brahmins to oversee religious rituals in the temples, giving rise to numerous agraharam in the Kerala region.

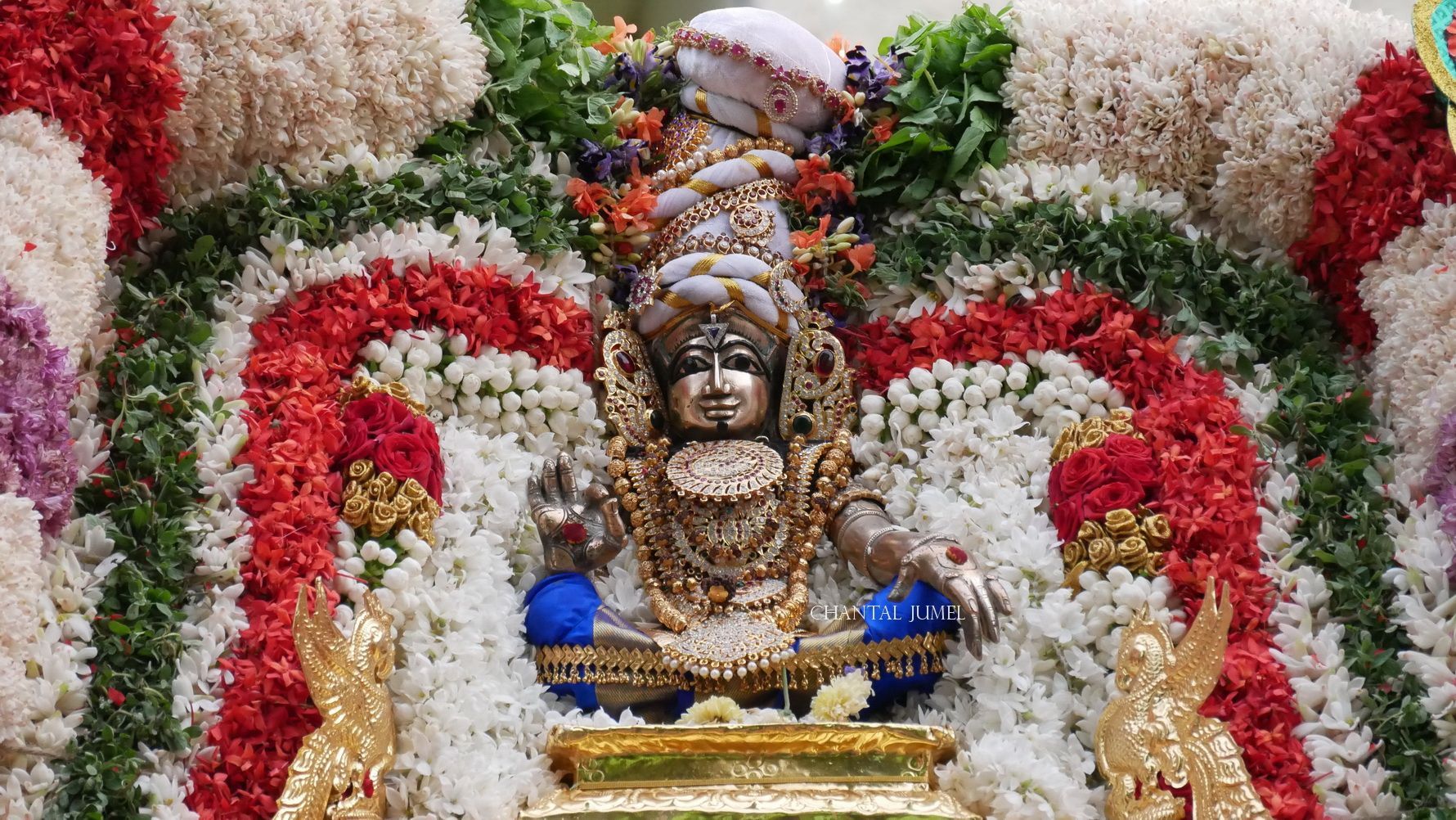

This is the story of the village of Nurani. As the families settled in and planned to clear the western part of the village, residents of the neighbouring colony reported hearing bells ringing and sensing a delightful fragrance in the air. Informed of these observations, the villagers began meticulous excavations at the site. Their perseverance was rewarded with the discovery of three cylindrical stones, a small granite elephant and a flat stone. After consulting astrologers, it was declared that the three cylindrical stones represented the deities Dharma Sastha and his wives, Purna and Pushkala. The flat stone was associated with the goddess Bhagavathi. Later, it was revealed that a Brahmin had once lived on this spot before the agraharam was built. He was a fervent devotee of Lord Sastha, and every year, he used to journey to the Aryankavu shrine, but with age he could no longer walk. One day, the Lord appeared to him in a dream and told him to keep the three idols in front of his house. The villagers believe that these statues are the same as those once worshipped by the Brahmin. Since then, the idols of Sastha and his wives have been placed in the agraharam of Nurani.

Though the present generation of Tamil Brahmins speaks Malayalam, they still maintain the traditions inherited from Tamil Nadu, especially the practice of kolam. When I studied in Kerala, I was surprised to find that there was less kolam than in Tamil Nadu. I did not understand the reason for this until I realised that this art was mainly practised by Tamil women, and that the woman who taught me was herself a Tamil whose family had been in Kerala for several generations.

In the Nurani neighbourhood, culture and spirituality are deeply intertwined, especially during the Sasthapreethi festival, dedicated to the Hindu deity Shasta/Sastha/Ayyappan. This year, in 2023, the festival takes place from 17 November to 30 December and corresponds to a specific calendar cycle known as "mandalakalam". This cycle begins on the first day of the month of Vrikshikam (mid-November to mid-December) and concludes on the 11th day of the month of Dhanu, which corresponds to the end of December. This is a period of intense austerity, especially observed in Ayyappan temples.

My visit was scheduled for the weekend in mid-December, and I arrived with my hosts at the temple entrance with undisguised joy. Once inside, I spotted a group of women and young girls happily chatting away. Having seen photos from previous years, I knew they will be painting the path leading to the shrine of Shasta/Ayyappan. The conversations were lively, and it is mainly young girls who were discussing the kolam that would adorn the floor today. To my surprise, they unanimously agreed to paint Warli motifs, a far cry from the traditional aesthetic of the kolam.

The Warli tribal community, largely settled in the state of Maharashtra, is renowned for its ritualistic pictorial art, a practice traditionally carried out by women. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, this art underwent a radical transformation as a result of a government development plan aimed at increasing the income of many tribal communities by providing them with paper sheets. It was during this period that Jivya Soma Mashe, inspired by the ritual paintings of the women of his village, began to paint and explore new forms of personal expression.

His fame quickly spread across borders, and he was invited to exhibit in some of the world's greatest museums, inspiring many young talents in his wake. Among them was Shantaram Tumbada, who had the opportunity to see one of his works displayed on one of the walls of the Musée Urbain Tony Garnier in Lyon, France. Warli art motifs are characterised by their simplicity, combining geometric shapes such as circles, triangles, and squares. The human body is represented by inverted triangles.

Thanks to social networks, these motifs of human representation have been widely shared and reproduced in a variety of media. The young girls have also embraced the trend for these streamlined figures and have appropriated the repertoire to create a painting. To achieve this, the corridor has to be divided into equal sections to integrate the patterns. The intergenerational team of women is inspiring, and their laughter brightens every moment spent in their company.

It is an exceptional opportunity to explore and participate in this tradition, which lies somewhere between performance art, religious asceticism, and a meditative path. Indian artistic traditions offer a particularly rich perspective on the relationship between man and the divine, and the role of women in these practices is of paramount importance. Through their art, they are able to transmit ancestral knowledge, preserve a cultural heritage and express their spirituality in a unique way.

The floor of the corridor is now prepared, and the nimble-fingered women draw the Warli musicians with liquefied rice paste, bringing them to life. It is as if the wind instrument tarpa, and the percussion resonate in harmony in this ephemeral painting where music and art converge. The longevity of the kolam is enhanced by using the wet painting technique.

As the evening puja approaches, the group rushes to finish the borders that will enhance the floor paintings. The doors of the sanctuary open and the priest pays homage to the divine image. In the soft glow of the oil lamps, as the devotees melt into prayer, the kolam, like visual hymns, captivate hearts in silence. Then, seated on either side of the paintings, men recite the Yajur Veda, a liturgical hymn and one of the four main Vedas of Hinduism. In the days to come, the women will return to the sacred enclosure to paint kolam as a graphic expression of reverence.

The next day I meet an enlarged group, with unfamiliar faces joining us. This time the paintings are of birds. Once again, the space is measured and divided, with each bird depicted within an ornated circle.

A majestic peacock leads the procession, followed by two pairs of parakeets and pigeons in an affectionate face-to-face encounter. At the end of the pathway, facing the sanctuary, a flamboyant eagle stands tall like a heavenly messenger, its feathers displayed in reverence.

Each day, in an unchanging cycle, the evening rituals unfold, and until the end of December, the women will make their way to the temple, faithful to their purpose, creating ever-new graphic offerings.

Follow the links...

To find out more about the worship of Shasta/Sastha/Ayyappan

To find out more about the worship of Shasta/Sastha/Ayyappan as a householder