Kerala Kalam, "Ayyappan, the hunter and the householder"— part 2

Ayyappan Tiyattu ritual is performed in the regions of northern and central Kerala. The paintings of the Nambiar community exhibit a perfect mastery of line. The three-dimensional effects add a sculptural dimension to the paintings and a liveness to the image of Ayyappan and the other characters.

India is sometimes confusing for a Westerner who is fond of rules and logic, of systems and classifications. He who strives to specify, delimit, and select thoughts, actions, and objects, he finds himself faced with a culture that has always favoured circulation, assimilation, non-resistance, flexibility, movement, plurality, and fluidity, resulting in contrasts, imbrications, crossovers, and tensions. In the world of kalam, depending on the community and local myths narrations, the deities take on different appearances. To me, and according to the Kuruppu painters, Ayyappan is depicted as an ascetic young prince or as the Lord of Sabarimala until I met the Tiyattu Nambiar, who portray Ayyappan as a bearded hunter or surrounded by his wife Prabha and son Sathyakan. The Tiyattu Nambiar of central and northern Kerala are ritual painters and belong to the Ambalavasi community as the Kuruppu. They are eight families attached to specific temples and their art is solely in praise of Ayyappan. The whole ritual performed with the aim of solving problems of the devotees and the entire community is a combination of floor painting, singing, narrative performance that resembles the oldest living Sanskrit drama Kutiyattam, and oracle dance.

The myth according to the Tiyattu Nambiar

A lesser-known interpretation of the myth about Ayyappan originated from the Tiyattu Nambiar community. To summarize this version, the story goes that a young and chaste Ayyappan mastered the sacred texts of the Vedas so well that he wanted to sit on the "all-encompassing knowledge throne" of God Indra. A furious Indra replied that Ayyappan being a brahmachari (celibate), he did not know the Kamasutra (treatise on the art of love). Therefore the young ascetic prince married Prabha and gave birth to a son named Sathyakan. Having fulfilled the ultimate condition stipulated by Indra, Ayyappan was able to outwit him and ascend the throne. After some time, Shiva sent his son to earth. Saturn gifted him his horse and thus he arrived in Kerala accompanied by eight families of Tiyattu Nambiar who settled down and built temples to worship Ayyappan.

Drawing the kalam

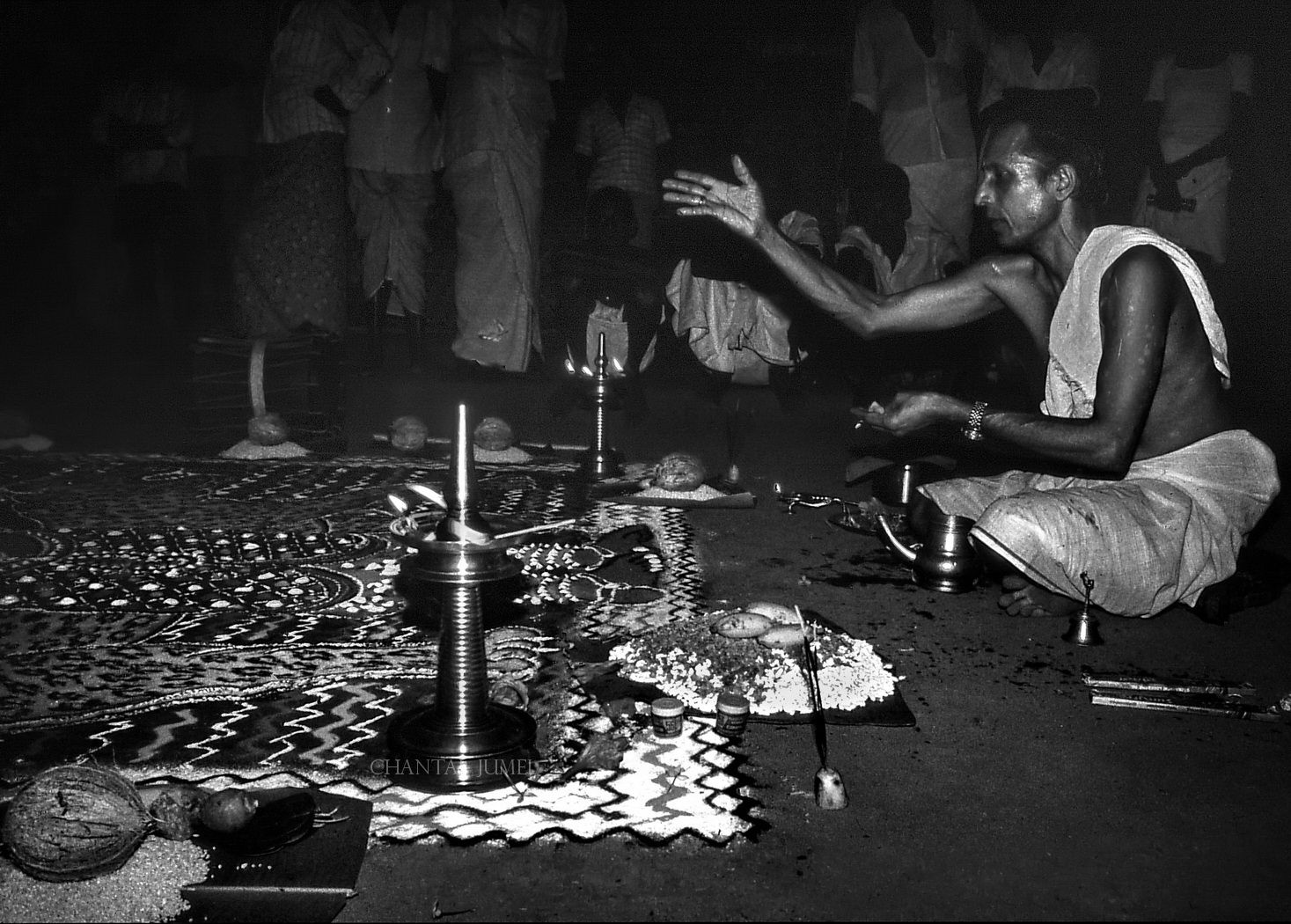

During my research, I saw two performances that took place in different families. The ceremony of drawing the kalam always begins with the preparation of a selected area, within the precincts of a household or in a temple mandapam (pavilion for the rituals). Above the enclosure, a canopy is erected over four logs wrapped up in unwashed cloth and forming the boundaries of the painting. The ceiling is then decorated with garlands of flowers, and kurutola or hanging fringes cut in the leaves of a coconut tree. A black cloth called a kura, spread over a network of ropes, completes the set-up, and announces the beginning of the ritual. There must be a consecrated area to invite the invisible world, and once the limits have been set, one takes off the slippers out of respect, and the painters' bodies bow out of humility, for the earth is preparing to host the painting that will be offered to the sight of the gods until the invoked deity descends to meet its devotees. The ritual always starts with prayers addressed to Ayyappan, Goddess Sarasvati, and God Ganesha, and is immediately followed by the creation of the kalam. There are many distinct images, each of which depicting a particular version of the myth. The basic representation is Ayyappan in standing posture, accompanied by a horse or a cheetah (usually mentioned as a tigress).

There is another floor painting much more elaborate called munnu-rupam kalam literally "three forms kalam". In this image Ayyappan is flanked by his wife Prabha on the left and Sathyakan on the right. I saw this grand performance in the temple of Thayankavu Sastha, in the district of Thrissur. It is one of the few temples where Ayyappan is seated along with his wife and son.

The drawing begins like many kalam, by tracing an east-west vertical line called brahmasutra or brahmakila. Then, the various parts of the body are drawn on both sides of the line. Five colours are used and will be combined both in their pure state and in shaded layers to create variations in hues.

To be effective, the paintings of the deities must be spectacular. The layered skirts of Ayyappan and his wife bear a likeness to some Teyyam costums (a ritual dance form in northern Kerala).

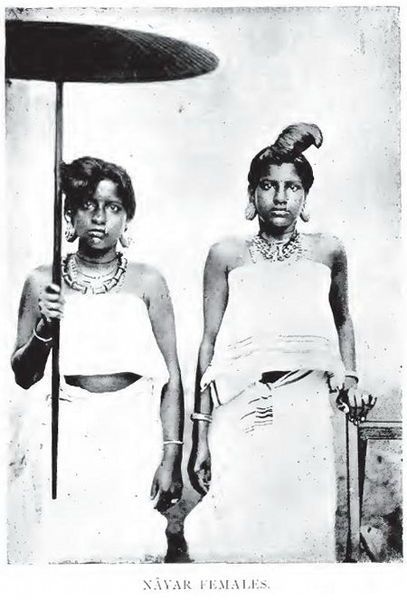

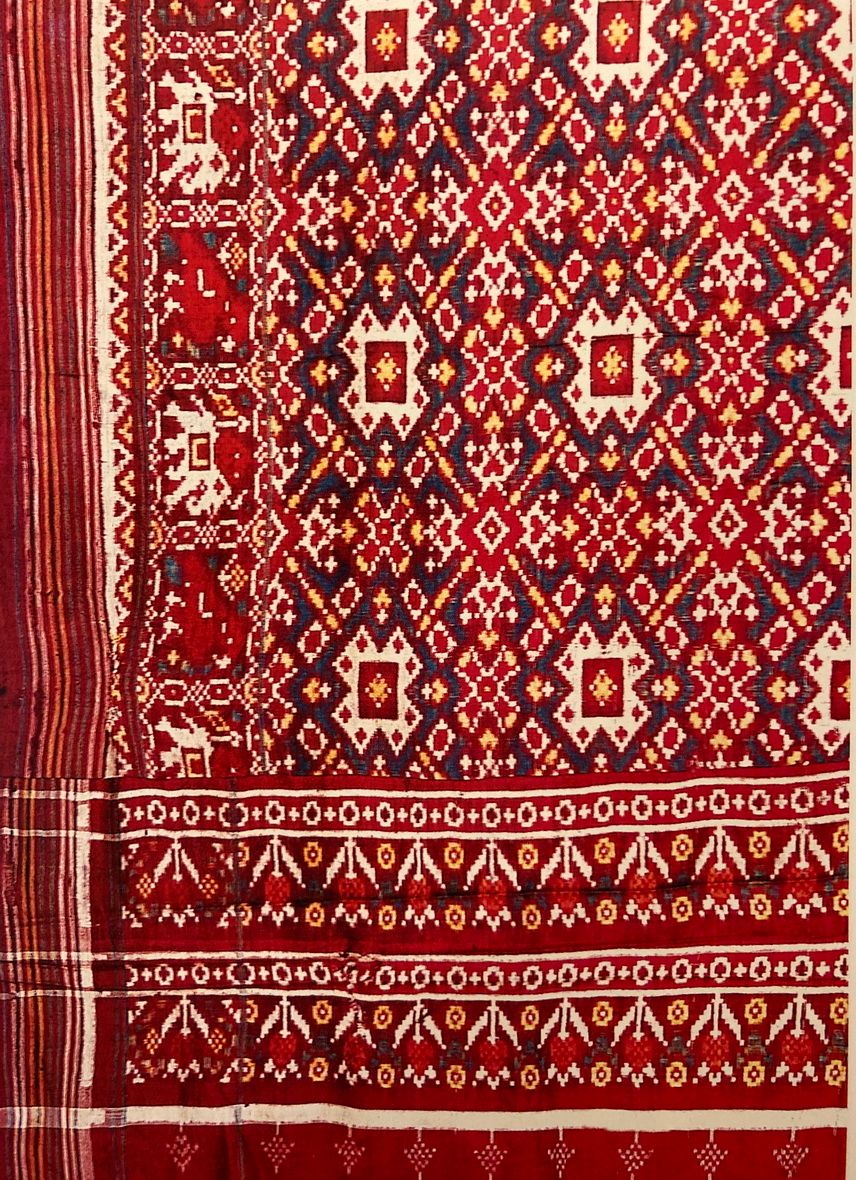

Ayyappan and his son Sathyakan wear a geometrical patterned cloth around the waist called virali patta ; an antique prestigious silk fabric greatly used in temple rituals, seen in Kerala murals, and traceable to the much priced pathola from Gujarat. They were most probably imported in Kerala in the seventeenth century up to eighteenth.

The paintings of the Nambiar community exhibit a perfect mastery of line. The three-dimensional effects created by numerous graphical techniques add a sculptural dimension to the paintings and a liveness to the image of Ayyappan and the other characters.

Narrating the myth of Ayyappan through hand gestures

Once the painting and the customary offerings are completed, a Nambiar performer comes forward and sits, facing the painting. Dressed in a red jacket, wearing a golden breastplate, wrists and ear ornaments, the performer becomes Nandikesvara, the faithful servant of Shiva who narrates through hand gestures called mudra the stories related to Ayyappan. It includes the birth of Ayyappan, out of the divine union of Shiva and Vishnu, in the form of Mohini. This narrative process is called Kuttu and, unlike in Kudiyattam or Kathakali, the facial expressions remain imperceptible ; the silent enactment being a liturgical drama and not an entertainment.

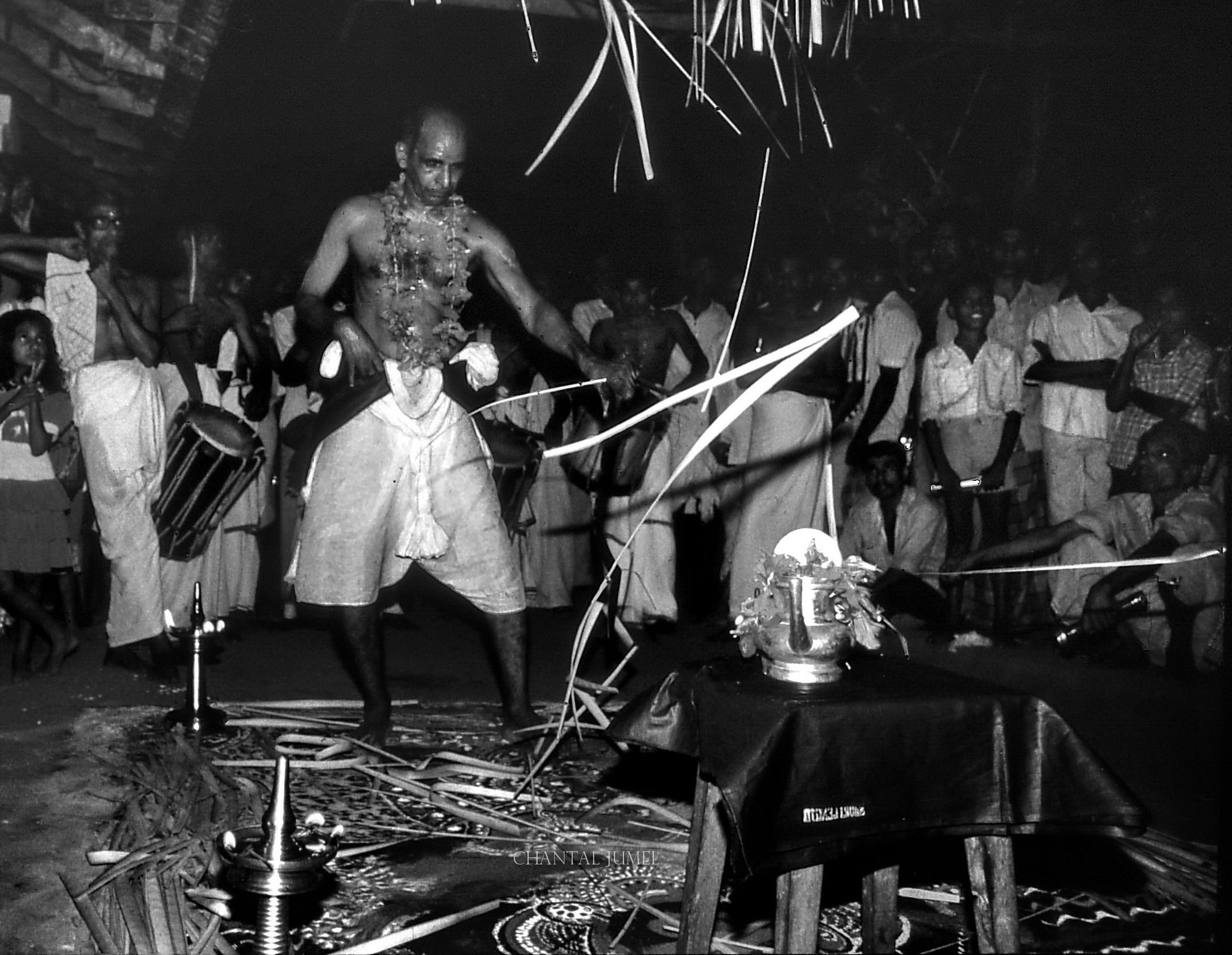

Kalathilattam, the dance in the kalam

After the silent narration of Ayyappan stories, the performer removes the costume and ornaments and wears a simple dhoti (a rectangular cloth draped around the lower body), then wraps a black scarf around the waist, and place a garland of hibiscus flowers around the neck. The whole family and some villagers are present. With a straight sword in the hand, the Nambiar or the temple oracle (depending if the ritual takes place in a private home or in an Ayyappan sanctuary) start to circumambulate the painting using slow and fast paced steps and various footwork accompanied by several chenda drums whose rhythm builds to a crescendo. At the precise moment when the music reaches its climax, he jumps into the kalam, chops one by one the vegetal fringes adorning the ceiling and wipe off with his feet the painting, except for the face of Ayyappan which is erased by hand with great reverence. The ceremony ends in silence. The kalam powders and cereal offerings mixed with flowers are distributed to the family members and participants.

Previous article :