Kerala Kalam,"Measuring and sketching the body"— part 3

Kalam paintings are not born of the priest's or ritual painter's own imagination; they are drawn according to precise rules, which include specifications about shapes and colours. A kalam begins, in most cases, by tracing an east-west vertical line called brahmasutra.

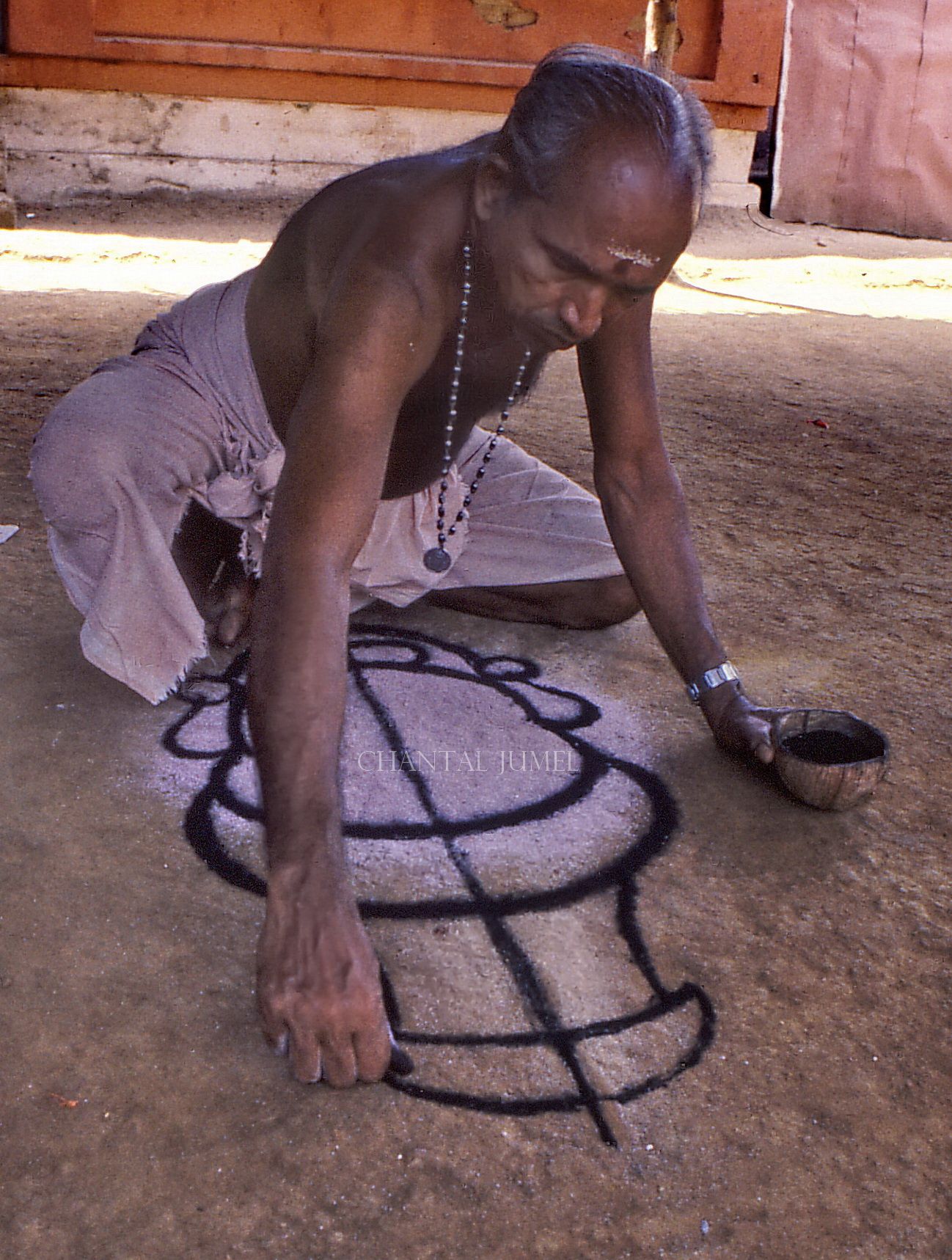

Early in the morning, the ritual painters prepare themselves to receive the divine presence. It is with a tactile memory, which they possess at their fingertips, that they dash a line from east to west; the axis mundi —the axis connecting heaven and earth — is traced through the divinity’s body. Sometimes, it is a skeleton of straight lines, circles and dots that they arrange until the hand becomes smoother and silently weaves all around the body, the glorious, earthly and material appearance of the invisible, heavenly, immaterial reality. These officiating men remain silent; their fingers run actively and their hands manifest what they have internalised through the practice of dhyana shloka, or meditation verses.

Measuring and drawing

Ephemeral paintings are not born of the priest's or ritual painter's own imagination; they are drawn according to precise rules, which include specifications about shapes and colours. Although the Shilpa Shastra mention several types of mathematical divisions to draw figures or idols, almost all of the ritual painters in Kerala define the dimensions of the entire body by using a unit of measure applied as a standard. This unit, known as the siras pada, is the height between the middle of the forehead and the chin of the drawn deity, and is used as a basic unit for the rest of the drawing. To enlarge or condense a painting, one therefore begins by lengthening or shortening the height of the face. Sometimes, the painter might use a unit of measure called musti, which starts from the elbow and extends to the clenched fist. He leans over until his forearm touches the ground, which he marks with black where his clenched fist reaches. He then repeats the process several times. As a result of these acrobatic gestures, the painter calculates the distance between the different body parts. A kalam begins, in most cases, by tracing an east-west vertical line called brahmasutra or brahmakila. Then, the various parts of the body are drawn on both sides of the line. The brahmakila has been explained thus by previous writers:

The middle-line (brahmakila) is the support, and the field (panel) should be divided by this middle line. They divide the field (panel) in two parts by the brahmakila which is the vertical middle line, like the post of mount Meru (merukila) on the earth, like the backbone in the animal, like the marrow of the tree, like the soul of the living being. Thus the line is verily a fundamental reality (satyam). It is the origin of form. (Boner, Sarma and Bäumer 1986: 69)

Brahmasutra or line of Brahma is the symbol of mount Meru, the axis mundi, similar to the center channel (axis passing through the body) in the human microcosm. (Tucci 1974: 89)

Although the descriptions above in general apply to many practices of drawing the kalam, the kalam drawn by the Parayan community does not start with the tracing of the brahmasutra but is instead built around a square divided into four equal parts. These components are similar to the panjara or a diagram of straight lines, circles and dots. The panjara is associated with a skeleton or the bones of a living organism.

The kalam of the Pulluvan, on the other hand, is similar to knotwork and develops using simple or complex graphs arranged in a specific pattern.

Kalam images show the divinities facing forward, standing or sitting, with or without mounts. The anatomy of these figures complies with standards usually recorded in canonical treatises. A perfect human being is not believed to exist, so such standards are not based on any ideal human model. This is the reason why the masters searched for models among animal and vegetal species, to describe each part of the human body and they thus created a composite ideal, as it were.

Such standards are transmitted orally from master to pupil and in general, from father to son by means of dhyana slokam, or meditation verses, most often in Sanskrit. Some of them provide basic guidelines about how to represent divinities; others are more philosophical but are of no material use as regards methods of drawing. It is mostly through the living practice of manual skills and immemorial knowledge that the beginner becomes fully familiar with the body’s postures and the proportion of the final image.

The article is a translated excerpt from my book : "Kolam et Kalam, peintures rituelles éphémères de l'Inde du Sud", Editions Geuthner, Paris 2010.

Previous articles :

- kerala-kalam-draw-and-sing-the-paintings-part-1/

- kerala-kalam-singing-and-dancing-the-paintings-part-2/

To watch the elaborate knotwork of the Pulluvan community using simple or complex graphs arranged in a specific pattern click on the links : Pulluvan 1 _ Pulluvan 2 _ Pulluvan 3

- The Shilpa Shastra, the Narada Shilpa Shastra, and the Vishnudharmottara Purana all dedicate chapters to painting. These ancient Sanskrit treatises discuss various aspects of a painting: measurement, proportion, the viewer’s perspective, mudra, emotions and rasa.