Jharkhand, Sohrai festival "Painting aripan to welcome the cattle" — part 5

When the liquid rice paste is ready for use, the women trace a graphic path from outside the house to the stable. If the latter is in the inner courtyard of the house, the line runs across the courtyard to the entrance of the stable.

Early in the morning, we set off again for Oriya, the first village I had visited. Today, several tribal communities celebrate Sohrai, the festival of crops and livestock, like its Tamil equivalent, Pongal. Justin, my guide, explains that the word Sohrai, refers to the gathering of animals in a fenced shelter or the action of whipping cattle. The word “soh” is used to drive cattle with a short stick or to chase birds or animals. So, perhaps the name of the festival itself traces the history of animal domestication and the beginnings of agriculture among the Adivasi (indigenous) communities of this region. We arrive at the village just as the men are taking the animals to bathe in the local pond. Later in the morning, on the way back, the cattle will return to the cowshed along a path decorated by the women.

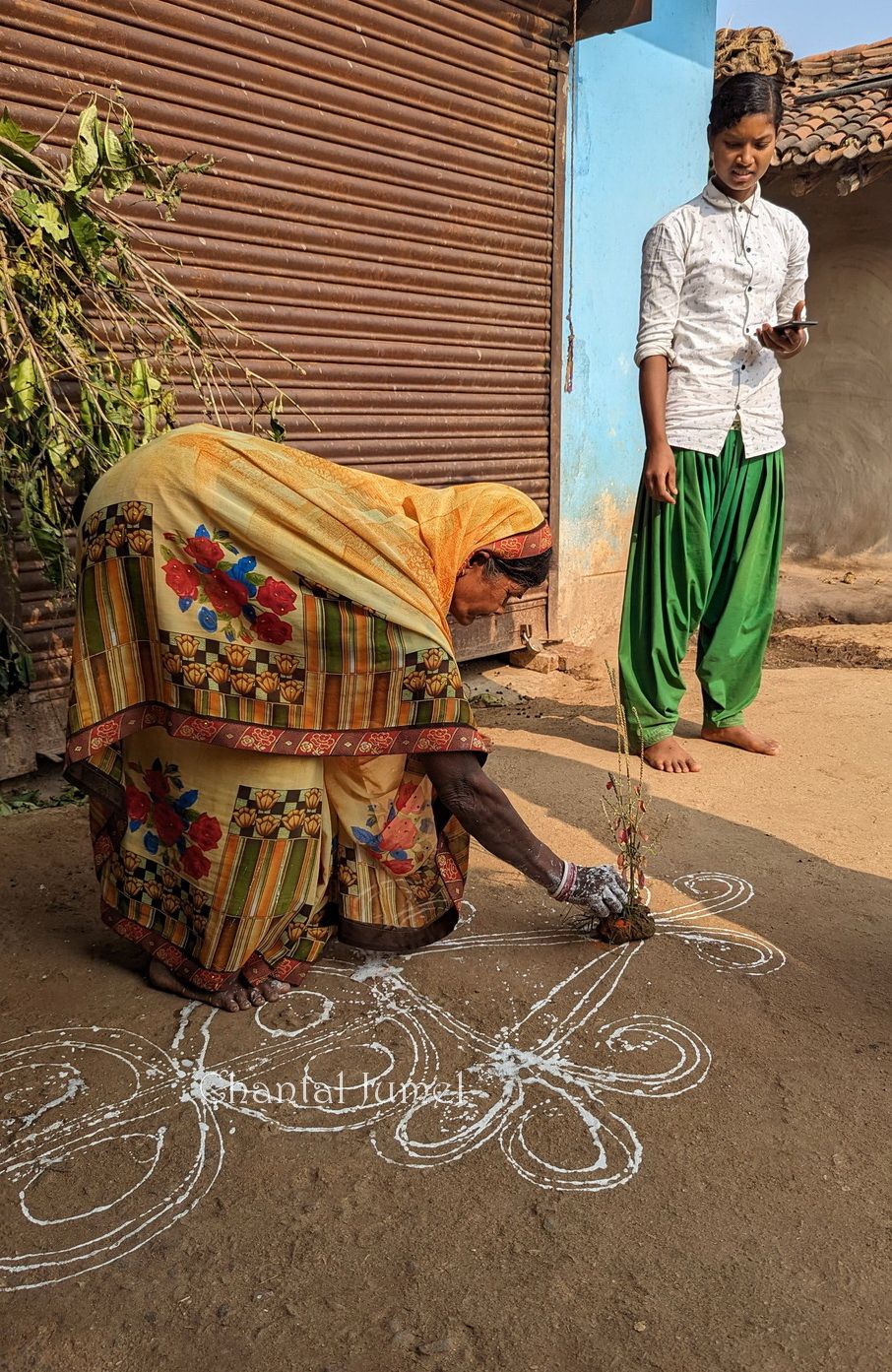

I waited years before I was able to observe this unique way of painting on the floor. Always on the lookout for filmed testimony, I came across an amateur video, shot in a region of Bengal called Purulia, of women painting on the floor in a unique way, that intrigued me. Dipping her whole hand in what appeared to be rice milk, a woman was drawing, letting the liquid run down her five fingers as she formed figures on the ground. I tried to understand the context in which she was painting in this way, until I saw a photo of a similar floor drawing posted on the blog of my guide, Justin Imam. After some discussion, it turned out that tribal women in the Hazaribagh region also paint for the Sohrai festival, which takes place just after Diwali, in the month of Kartik (mid-October to mid-November).

The daily ritual begins with sweeping the courtyard and applying a primer made from cow dung. Liquefied rice flour is then prepared and used to draw on the ground. The rhythmic pounding of the dekhi (rice pestle) can be heard in the surrounding houses as the husk is removed from the rice.

The resulting rice flour is mixed with water and a vegetable binder extracted from a wide range of plants, including okra (Abelmoschus esculentus), known for its sticky texture due to its high mucilage content. The lightly crushed vegetables are immersed in a bucket of water. After a while, the water becomes sticky, and its degree of viscosity is tested several times until the expert is satisfied with the result. After filtering, the sticky substance obtained is mixed with the liquefied rice paste. During mixing, the solution is frequently checked by dipping the hand and lifting it several times to test the flow along the outstretched fingers. However, the mixture must be applied immediately after preparation, otherwise it will coagulate.

When the liquid rice paste is ready for use, the women trace a graphic path from outside the house to the stable. If the latter is in the inner courtyard of the house, the line runs across the courtyard to the entrance of the stable. The rice milk is poured into a dish that is wide enough for the hand to brush the surface of the liquid and what sticks to the palm of the hand is guided by the thumb along the four fingers, falling back in diffuse lines. The linear design, comparable to a climbing or creeping plant, consists of a straight line and circular patterns on either side of the line, ending in a triangular or rectangular pattern.

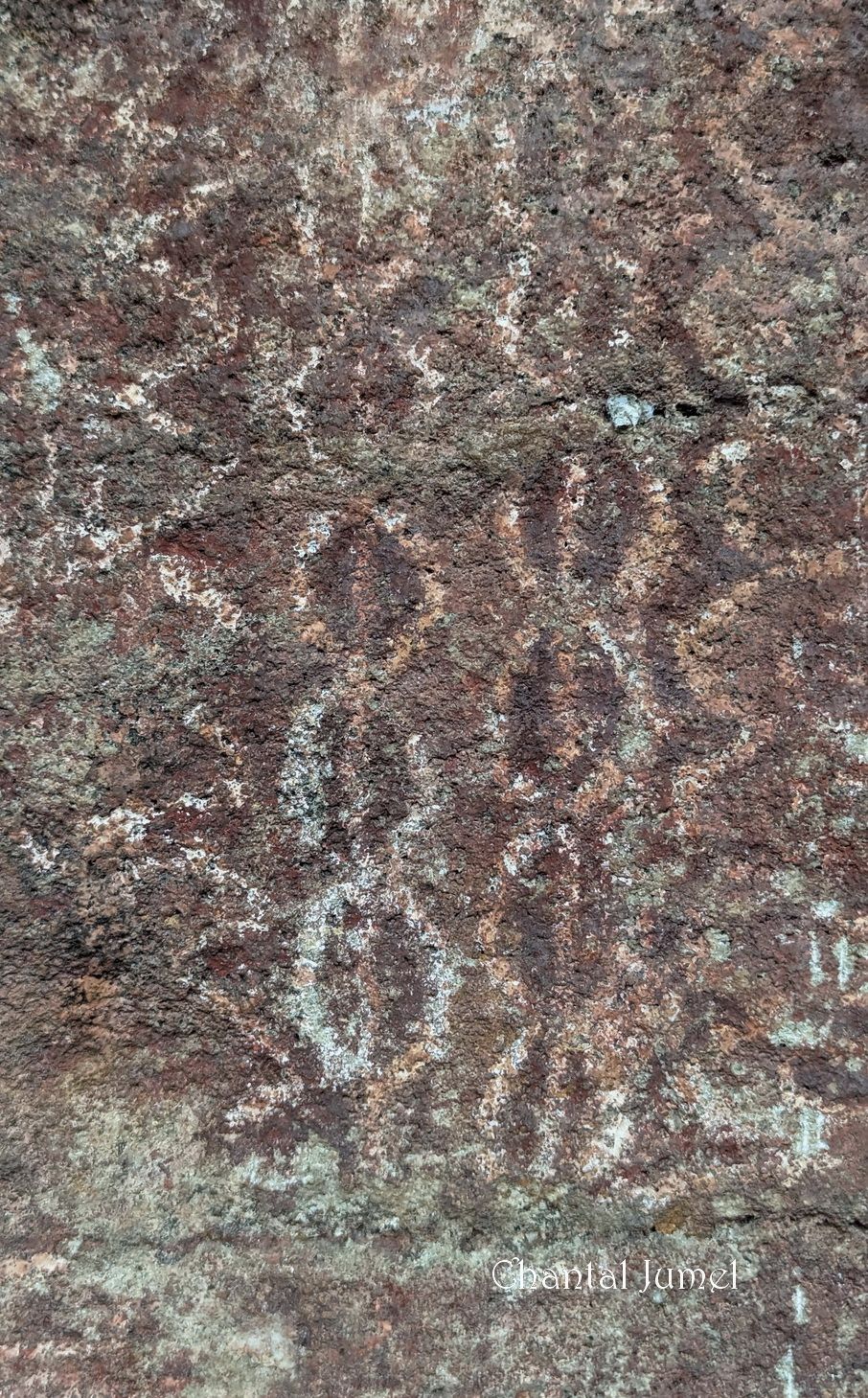

Bulu Imam, who took an interest in the rock paintings at the archaeological site of Isco, not far from Hazaribagh, pointed out the similarity between a motif adorning the wall and the aesthetics of the aripan paintings. Having also visited the site during my stay, I noted the similarity with the aripan painted for the Sohrai festival. According to Bulu Imam, the circular motifs framing the central line are cow or buffalo hooves. This suggestion is supported by similar images found elsewhere in India in floor drawings in honour of cattle.

Once the painting is complete, vermilion powder is applied at regular intervals along the central edge of the motif. Finally, the women make clods of cow dung into which they press a plant known locally as latlatiya, which is said to cling to clothes, and durva grass (Cynodon dactylon) which is used in Hindu rituals. Stories vary about the symbolism of these herbs. Some say they are used to ward off the evil eye, others to attract wealth.

Finally, when the cattle return to the cowshed, the men wash the horns and anoint them with mustard oil and vermilion powder. The coats of the cows, bulls and buffaloes are marked with circles using clay lamps dipped in colour or rice milk. Others dip the palm of their hand in white or coloured liquefied rice paste and place it on the animal's body to protect it from the evil eye.

Women do the same for stable lintels, ploughshares, hoes, and tractors. The tribal world also has a vast and varied repertoire of songs about the activities of daily life, festivals, nature and so on. Here is an Oraon harvest song by Rosalia Tirkey, mother of Philomina, the companion of Bulu Imam:

“For twelve months bullocks, we beat you and drove you; but today we will praise you and give you affection. Hario! On which horn will you take the tassel of rice sheaves? On which horn will you take the oil and vermilion? Come we will feed you rice.”

" Oraon songs and stories" by Philomina Tirkey, Bulu Imam, Lambert Academic Publishing, 2015

An invitation to a festive meal concludes the morning.

Story to be continued...

Previous articles:

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "An endangered heritage" — part 1

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Painting the walls for Sohrai" — part 2

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Painting the walls for Sohrai" — part 3

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Diwali at the Sanskriti Center" — part 4