Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Painting the walls for Sohrai" — part 3

In Hazaribagh, this art of scratching is the hallmark of the Kurmi tribal farming community to which Rudhan Devi belongs. I watch as she prepares a new section of a wall to be coated with manganese oxide, or “kali-mati,” mixed with water. This deep black pigment was used in cave paintings.

This year, Sunday, 12, November 2023, is a public holiday in India. Among the dates on the religious calendar, Diwali is an important Hindu festival that takes place every autumn at the time of the new moon between late October and early November. Symbolising the triumph of good over evil and light over darkness, Diwali celebrates the return of Prince Rama after many years in exile.

The Ramayana, one of the founding texts of Hinduism, tells the story of Rama's journey to Sri Lanka to rescue his wife Sita, who was being held captive by the demon Ravana. On his return, he is welcomed to the kingdom of Ayodhya by his people, who light the way with oil lamps. While the majority of Indians celebrate this festival, the tribal world attaches little importance to it, as tomorrow they will be celebrating Sohrai, the festival of cattle and harvest.

At dawn I hear voices and singing from the side of the main house. I met the two women from the day before, who have finished whitewashing the adobe house that Justin, my guide, and his brother Jason had built to house artists. The thickness of the walls, made entirely from their own excavated soil, protects them from the heat, and their surfaces are devoted entirely to murals.

It was in front of the long surrounding wall that I met Rudhan Devi, an artist whose immense talent I was about to discover. As I approached, I noticed a four-pronged comb between her fingers, with which she was scratching the kaolin plaster she had just spread on a low wall.

This graphic technique is similar to the art of sgraffito, from the Italian graffiare (to scratch), which consists of creating ornaments, symbols, or figurative scenes by hatching, scratching, or incising a white layer on a black or coloured background to reveal the underlying colour.

Sgraffito was mainly used to decorate houses and palaces and was very popular during the Renaissance and Art Nouveau periods. For those who live in Paris, there is the magnificent "sgraffito" facade on rue Mouffetard, depicting pigs, deer, goats, and poultry, originally intended for a delicatessen.

In Hazaribagh, this art of scratching is the hallmark of the Kurmi tribal farming community to which Rudhan Devi belongs. I watch as she prepares a new section of a wall to be coated with manganese oxide, or "kali-mati" mixed with water. This deep black pigment was used in cave paintings.

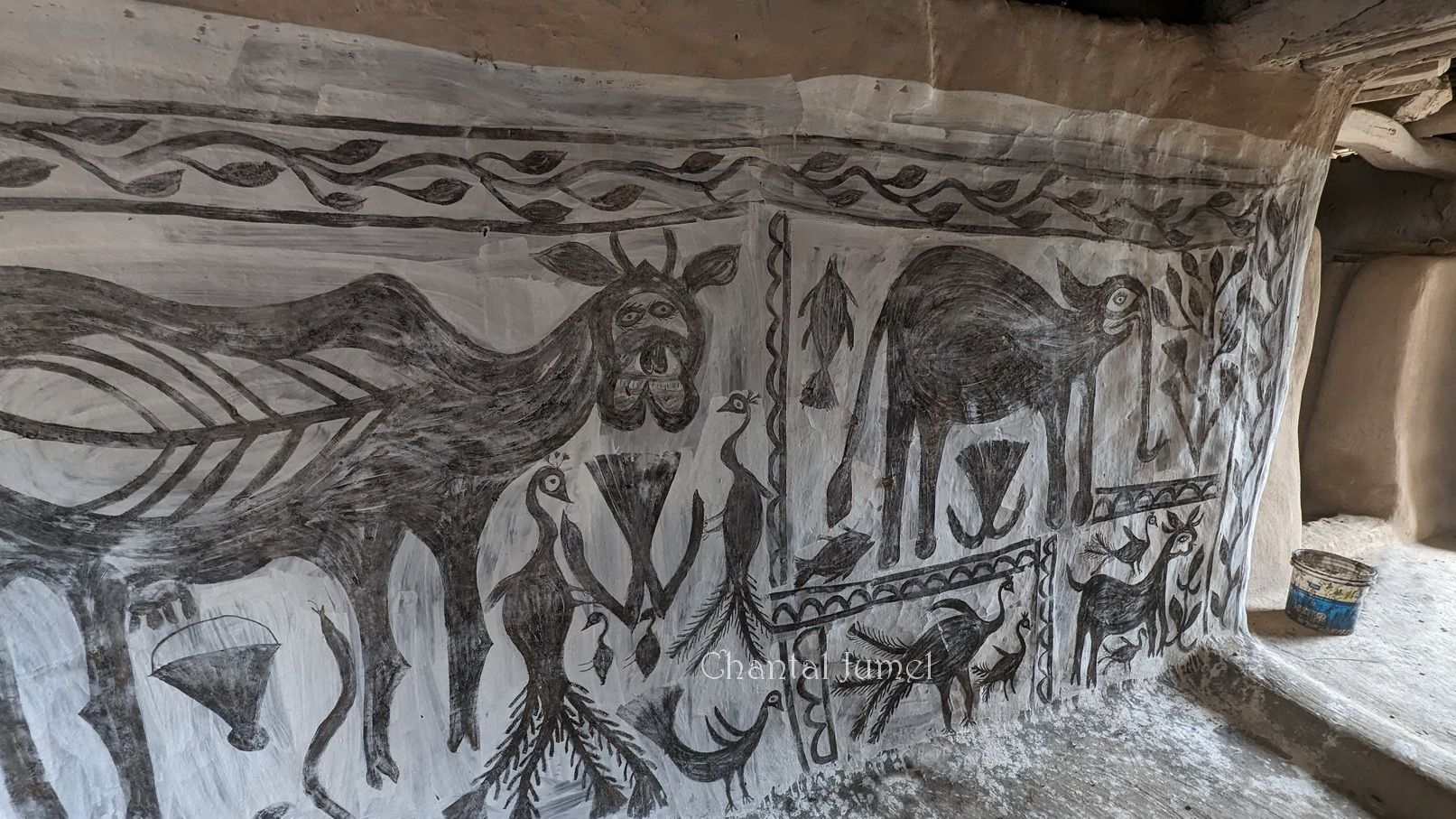

Before the black coating is completely dry, Rudhan Devi covers it with a layer of kaolin called "dhud-mati", literally "milk of the earth". Then, using the few teeth of a comb, she cuts and scratches the surface, taking us back to the forests of her childhood, where elephants, tigers, leopards, deer, and wild birds such as peacocks, moorhens and herons could still be seen.

But not far, just a few kilometres away, grey fumaroles float above the dwellings, enveloping the landscape in an ominous dust that bears witness to a devastated land, devoid of colour, animals, and greenery, populated by machines that swallow up bucolic villages day after day to extract coal, sacred groves where the spirits of the ancestors reside, tribal council sites, divinised hills, and springs inhabited by spirits. After returning from this trip, I read in the press that the Indian government is planning the ninth auction of commercial coal mines to boost national production. For the moment, far from this supposed progress, Rudhan Devi is drawing the outline of an elephant holding a lotus.

Behind him, a peacock has stretched its tail across the bottom of the wall, and some puzzled deer are chewing leaves while another peacock seems to be peering into the mouth of an animal. In the final panel, a fawn faces a wildcat, frozen in a position of attack.

It is breakfast time and, like the day before, we are on our way to a village called Jorakath, inhabited mainly by the Hinduised Kurmi community. After an hour's drive, at a crossroads, we take a side road. As soon as we enter it, we are plunged into a world of darkness and the roar of lorries loaded with coal. We also meet "black faces" who, instead of pedalling, are struggling to push their bicycles, on which dozens of sacks of coal are ingeniously stacked to supply towns and villages.

But this activity is forbidden by the penal code and coalfield laws, and these thousands of outlaws are part of a vast network that produces thousands of tonnes a year. I am outraged by this Dantesque atmosphere, worthy of a futuristic film. Elsewhere in Jharkhand, the town of Jharia is infamous for a coal mine fire that has been burning underground for almost a century, digging chasms in the ground that collapse and swallow everything in their path. On the road, too, hanging coal bins criss-cross the landscape like a fairground attraction.

Then the nightmare finally ended, nature gradually regained its colours, and the road literally became a path of light as mica flakes detached from the layered blocks on the sides of the forest road were embedded in the tarmac. The Hazaribagh region in the state of Jharkhand produces around 50 per cent of the country's total mica output.

When I was studying Kathakali in Kerala, I remember that once the make-up had been completed and the character's costume was put on, we would pass around a cloth bag of mica flakes, to sprinkle on the face to illuminate the make-up. The coveted mica, the geographical origin of which I did not know, was a rare and expensive commodity in South India, so it was distributed sparingly.

After an hour's chaotic drive, we reached the village of Jorakath, surrounded by gardens full of life and freshness. They contrast with the facades of the houses, most of which have no murals, except for the exterior and interior walls of Mainwa Etwaria Devi's farmhouse. I was struck by both the simplicity of the drawing tool and the richness of the mural motifs on the façade. The jungle and its inhabitants occupy a central place, and the distribution of animals, birds and plants is left entirely to the artist's discretion, although certain iconographic formulae seem to be repeated. The long corridor leading from the entrance to the courtyard is also populated by forest animals, fish, and plants.

As we enter the courtyard, followed by a swarm of children, Mainwa Etwaria Devi is coating a wall with manganese oxide mixed with water, followed immediately by a layer of kaolin.

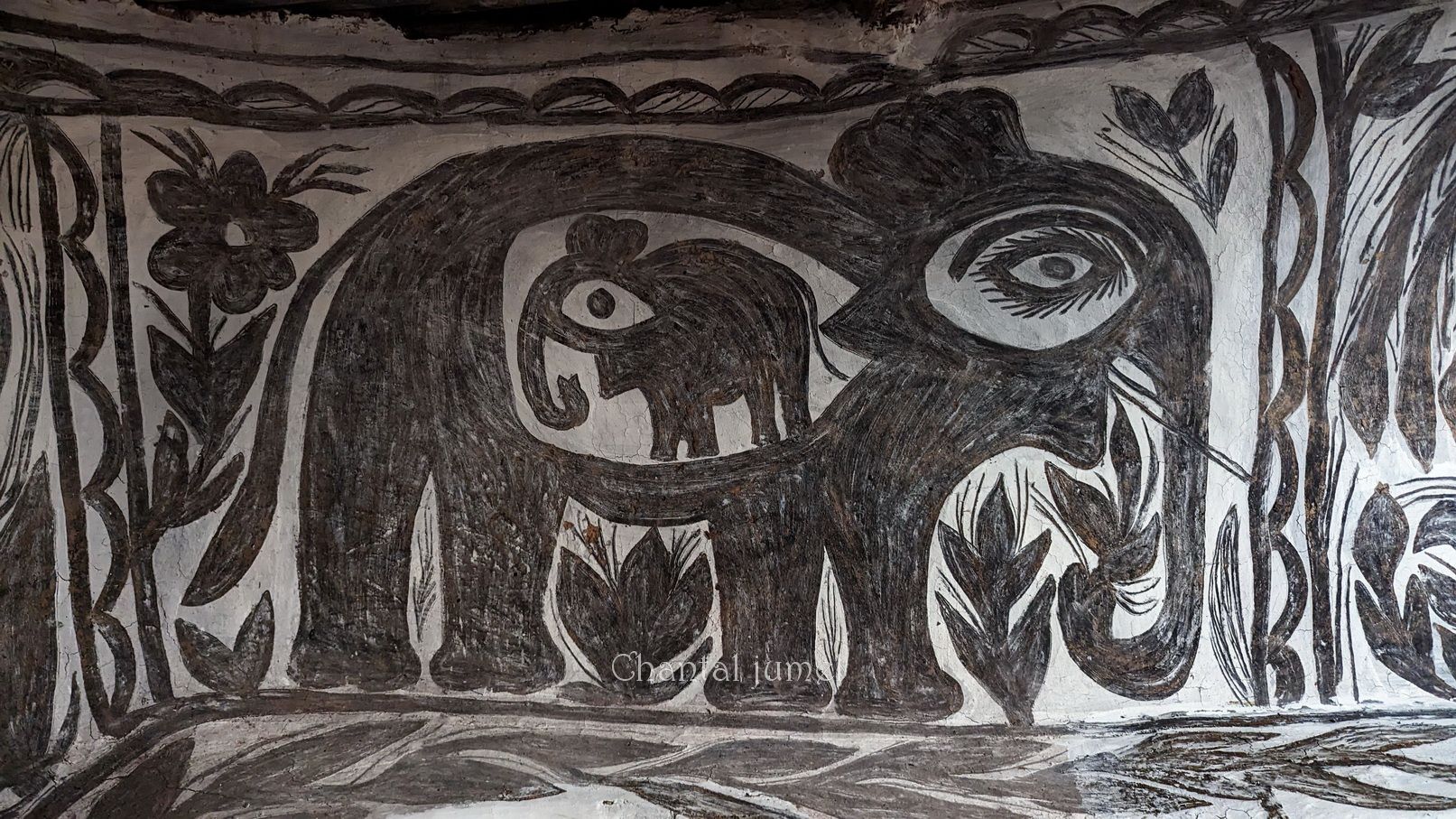

Then, with a piece of comb in her hand, she brings out an elephant, a peacock, and some plants, which she surrounds with a simple frieze. I notice that the elephant is swallowing a leaf that is partly in its mouth and partly in its stomach, in the form of a food bowl, as in the so-called radiographic paintings of the Aborigines of Arnhem Land in Australia. It is a peculiarity of this style of sgraffito painting for which I find it difficult to find an explanation.

Elsewhere, in Phulaso Devi's house, two elephants face each other. Above them, a frieze shows peacocks pecking seeds from a bowl.

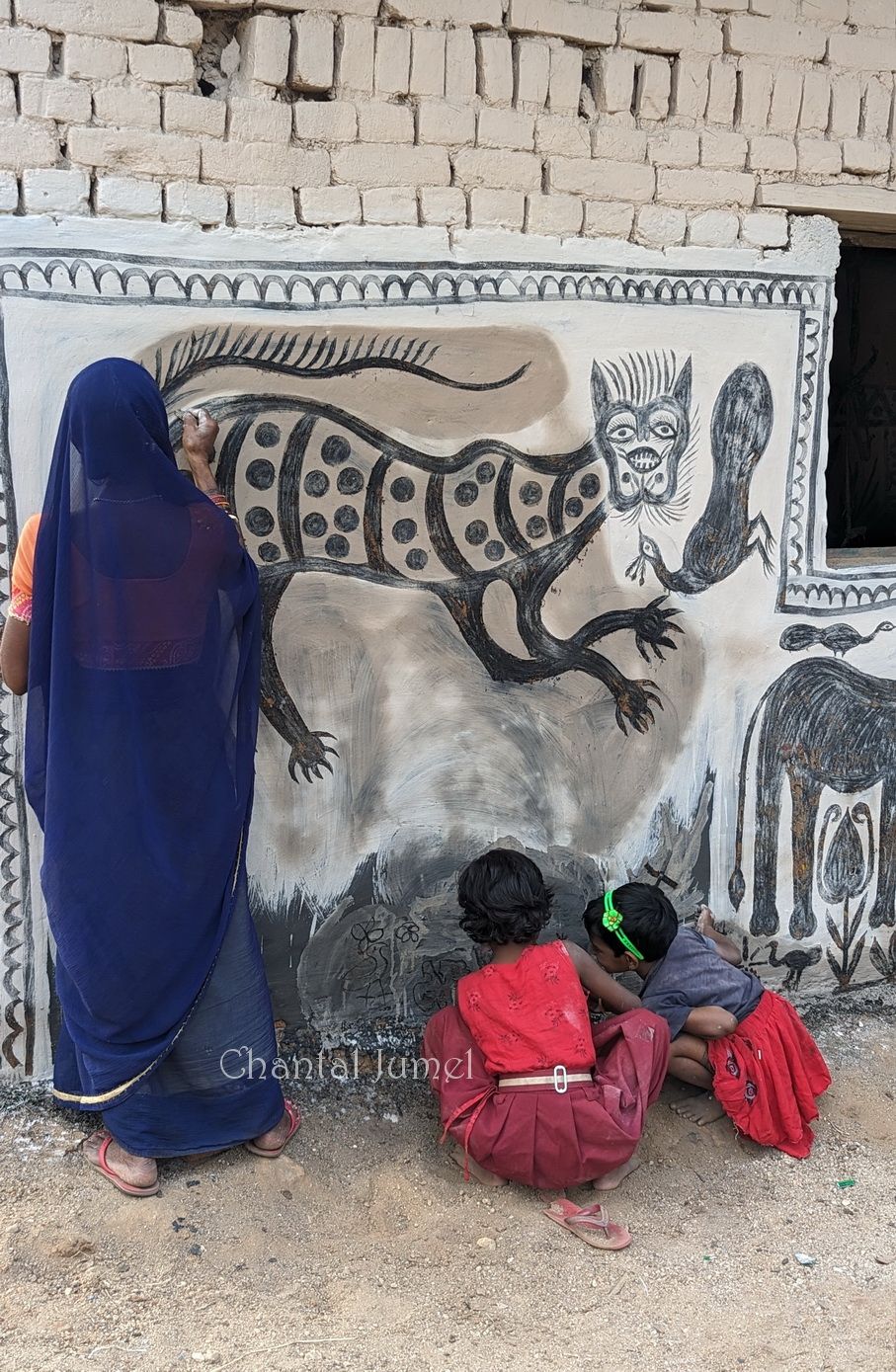

The last house we visit is that of Malo Devi. Standing in front of the outer wall of her house, she greets us, surrounded by her two young granddaughters, who gaze longingly at the pieces of a comb used for drawing. Little by little, the artist reveals a very friendly feline with stripes and rosettes.

Whether it is a tiger or a leopard, the artist's hand fascinates with its dexterity and the little girls, whom we encourage, end up taking over the lower part of the wall and a narrow vertical surface. Watching them, it is easy to see how difficult the technique is. If the black paint underneath is too wet, the comb will struggle to create a pattern on the layer of kaolin. After many attempts, miniature peacocks or cranes emerge from the wall.

Another day comes to an end, and we return to Sanskriti Centre to celebrate Diwali.

Story to be continued...

Previous articles:

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "An endangered heritage" — part 1

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Painting the walls for Sohrai" — part 2