Kapaleeswarar temple, the chariot festival

Processional chariots (ratha in Sanskrit, ter in Tamil) are an integral part of temples and public life in South-India. It is therefore normal to find in the kolam repertoire a rich collection of chariot designs dedicated to the gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon.

Sheltered in the heart of Mylapore in Chennai, the Kapaleeswarar temple is one of the most popular shrines dedicated to God Shiva. What is surprising in Tamil Nadu are the monumental temple entrances called gopuram, built in all cardinal directions. When I look at these stupendous towers decorated with multi-coloured stucco figures, I get an idea of what the polychrome statuary of Greek and Roman temples might have looked like. The image of classical Antiquity draped in pristine and gleaming white marble is so ingrained in the Western imagination that it is difficult to imagine a past as vibrant as these South Indian statues of gods, goddesses, and heroes. The colourful figures are an invitation to plunge into mythical India and decipher the stories they display on each level of the tower. Besides the temple, this multicultural area of Chennai is also a favourite place to shop for silver and gold jewellery, puja items, handicraft, and Bharata Natyam dance accessories. The whole neighbourhood is the place to be for dancers and Carnatic music aficionados who meet at various sabha (organization involved in the promotion of fine arts) during "December season".

Between the sacred pond and the temple, I like walking through the crowded East Tank square lane where fortune tellers and their green parrots invite the walkers. The gentle bird steps out of its cage and picks out one by one the cards of your destiny. The cards represent deities from the Hindu pantheon, not to forget Jesus and Allah. A little further, palm readers carefully examine the lines and mounts in your hand. Chanting incantatory mantras, they reveal your future and advise remedies and pilgrimages to counter evil eye and adversity.

At one end of this narrow street, women from the "Nari Kuravar" community, dressed in a skirt and half-sari, sell glass bead necklaces to tourists and women who have come to the temple to worship.

As I walk along, I am overwhelmed by a whirlwind of colourful and fragrant sensations that guide me through the alleyway leading to the main entrance of the temple. It is in this realm that, from morning to night, skilled hands weave garlands of jasmine, marigolds, tuberoses, or roses intertwined with the trifoliate leaves of the Bilva tree (Aegle marmelos). Three leaves to suggest the third eye of God Shiva, the Lord of this temple and husband of Parvati, known here as Karpagambal.

Panguni festival, when the deities come out to bless

Of all the documentaries on India, I remember an excerpt from Phantom India shot in 1969 by the French filmmaker Louis Malle in 1969. The second episode called "Things seen in Madras" (currently known as Chennai) focuses on various cultural and religious aspects of the city. The moment that caught my attention was a huge multi-storey chariot that moves forward by the sheer force of the arms of a frenzied crowd of devotees. Little did I know that one day, I would also be in Mylapore during Panguni festival, watching the same flamboyant chariot swathed in colourful panels and cylindrical cloth hangers (thombai) with appliqué designs. The Panguni festival (which takes place in the month of Panguni, mid-March, mid-April) is a ten-day festival celebrated at Kapaleeshwarar temple. Every year, I join the throng of devotees who hail from Mylapore and from other parts of the country. Although there are parades every day, some chariots attract huge crowds. Shortly before the start of the religious festivities, the streets around the shrine are the scene of various transformations. Potholes in the roads are filled in and simultaneously holes are dug in the tarmac to drive in the canopy pillars on the four "Mada veethi" (Mada streets) around the shrine. Later, the decorated canopies are hoisted by various groups of helpers. Every day, the processions are accompanied by musicians playing nagaswaram and tavil who perform at various locations.

Strange as it may sound, the British Raj and its musical bands have left their mark on traditional temple music. This influence can be heard during the Rishabha Vahanam procession when the bearers of the palanquin carrying the idol of the bull Nandi, the mount of God Shiva, start dancing to the tune of a Western song "For he’s a jolly good fellow", a rather incongruous note in this atmosphere of religious fervour. The seventh day is dedicated to the majestic temple chariot (ter in Tamil) procession. God Shiva is depicted holding a bow while seated on a throne with his wife Karpagambal, and God Brahma can be seen pulling the reigns of the sculpted horses.

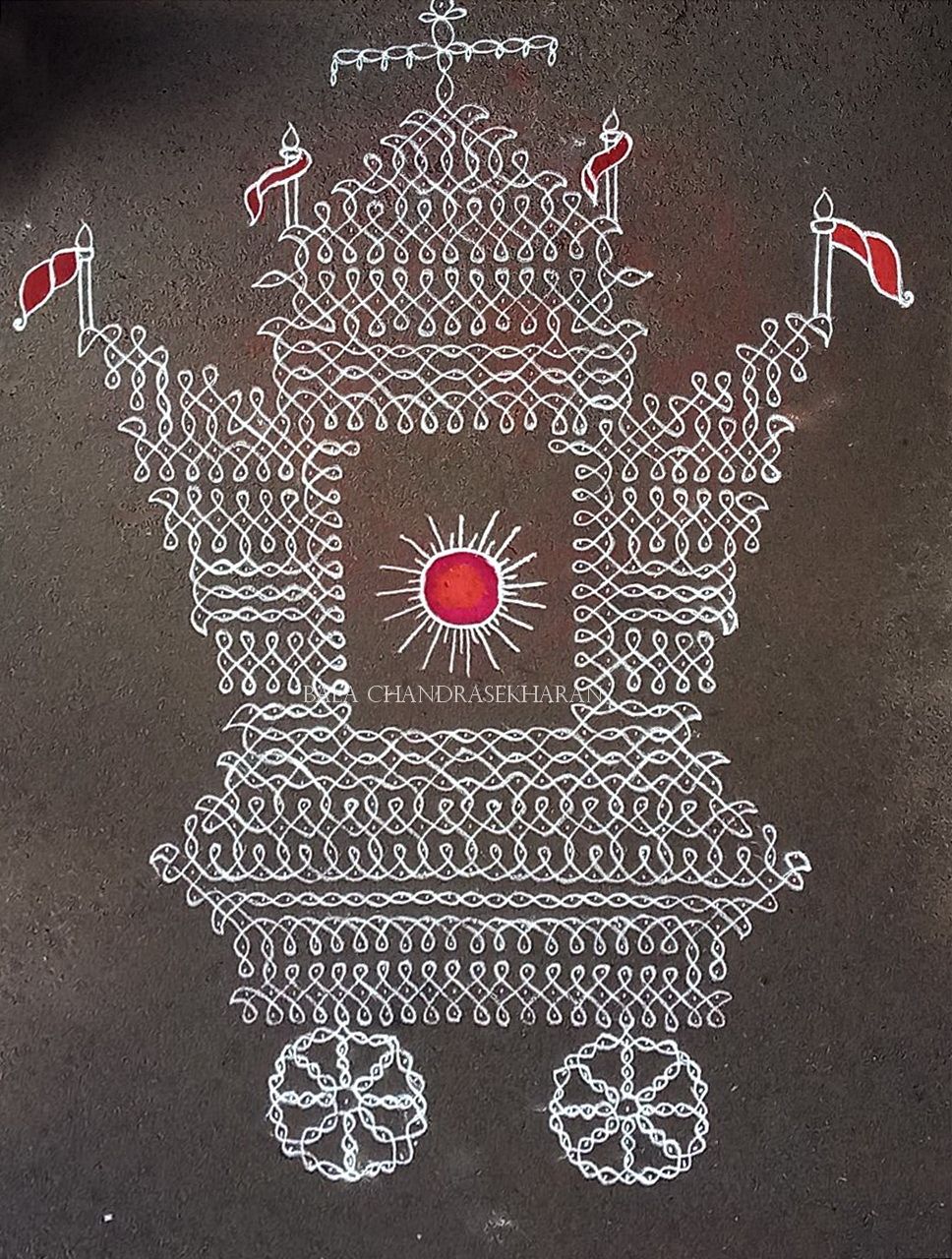

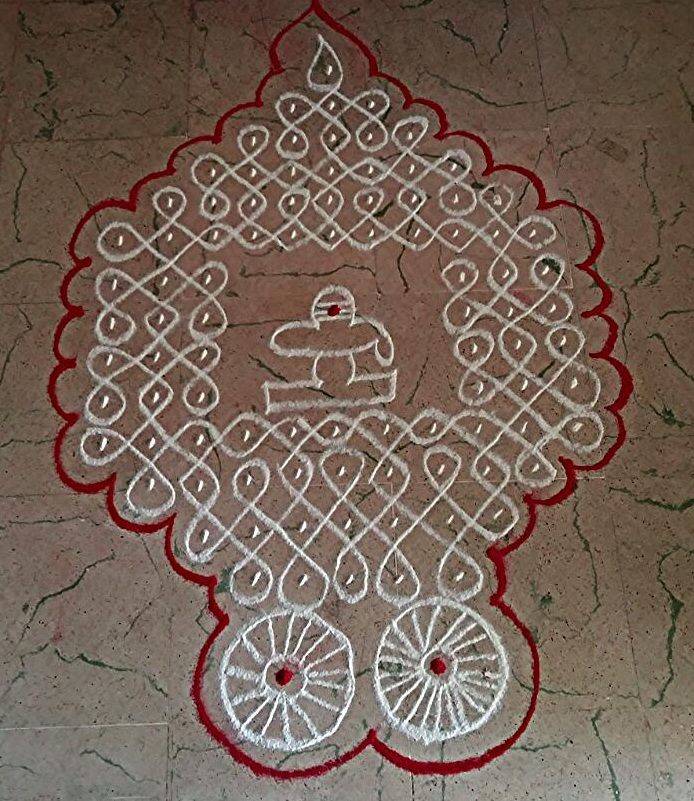

On the morning of the procession, women of the neighbourhood rush out of their homes to draw kolam under each canopy. "Hic et Nunc" here and now, they hastily weave the benevolent lines between earth and heaven to invite the deities to come down and meet their worshipers. The white written laces unfurling in the streets and mandapa infuse the audience with a sense of completeness before the wheels of the divine chariot scatter the powdered offerings.

Some men and women standing in front of the rolling chariot blow conches to welcome the divine couple, Shiva and Parvati. Then, at the heart of the crowd, a wave of barefoot men starts to move. The back-and-forth of bodies stretched to the limit is reminiscent of a tug-of-war game, except that the opponent is a huge carved wooden processional chariot mounted on human-sized wheels. Pulling, pushing, and dragging the chariot around the temple is an act of collective penance and an act of personal piety seen as a path to spiritual liberation. Thousands of jubilant believers gather in the streets to make offerings, pray and encourage the participants, as watching a procession is a unique opportunity for some of the devotees who were not allowed inside the shrine due to caste or sectarian restrictions not so long ago.

Chariot, a prominent feature in South-Indian temples

In India, processional chariots (ratha in Sanskrit, ter in Tamil) are an integral part of public life and temple ceremonies. Every important temple celebrates a chariot festival at least once a year and the deities are carried around on these mobile shrines. It is therefore normal to find in the kolam repertoire a rich collection of chariot designs dedicated to the gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon. According to the Hindu and Tamil religious calendar, one finds chariot kolam dedicated to the Sun God for the festival of Surya Pongal and Ratha Saptami, then to God Shiva for the festival of Thiruvathirai, etc. It is the symbols in the centre of the kolam that define the identity of the deity.

Women devotees drawing kolam during Panguni festival.