Kerala Kalam, “Visiting the Kalamandalam School” — part 2

K.P Ravishankar, is waiting to explain the day's schedule, which includes a visit to the Kalamandalam, an institution founded in 1930 by the poet Vallathol Narayana Menon. Over the years, the school has become one of the main centres for the study of classical Indian arts.

As the first rays of sunlight begin to dispel the night, I hear the call of the birds around my host’s house. Among the first to greet the day is the Greater coucal, known in Kerala as chakora or uppan, with its deep, distinctive call.

This solitary bird, with its dark silhouette, attracts attention with its coppery orange wings and piercing ruby eyes. Considered a harbinger of good fortune, it is said that those who hear its song early in the morning are assured of a successful day. The most famous work of Ramapurathu Warrier, an 18th century Kerala poet, is Kuchela Vrittam, which tells the story of Kuchela, a poor Brahmin and childhood friend of Lord Krishna, who travels to Dwaraka to meet him. In just a few lines, the poet sets the tone for his journey, which begins under auspicious circonstances:

“His way was charmed, for to his right. There alighted sweet chakoras, whose songs of joyous melody he heard as he stepped forth.”

Kuchela Vrittam, Ramapurattu Warrier, translated from the Malayalam by Reade Wood.

As I savour a chai (Indian tea) and contemplate the sunrise, other birds join in the morning symphony. Yellow-billed Babblers are on the prowl for insects, meticulously probing the roots of garden plants. They are unmistakable as they move in flocks, are noisy and chatter incessantly. A pearl-necked turtledove, perched on an electric wire, cooing softly while peacocks stroll leisurely through the garden. Outside my bedroom window, Purple-rumped Sunbirds hover like hummingbirds around the hibiscus bushes. They live close to the flowers because they feed mainly on nectar. In this harmonious cacophony, there are many others, such as the Orphean Bulbul, the Green Barbet, the Royal Fork-tailed Drongo, and so on.

Even if I had read and re-read "The book of Indian Birds" by the famous Indian ornithologist Salim Ali, it would have been impossible for me to identify all the birds without the BirdNet application. While some birds are within sight, others can only be identified by their calls or songs. BirdNet, a marvel of technology, is a software application that records a bird's song or call via the phone's microphone, then uses an algorithm to analyse the sounds, compares them with a database of bird songs from around the world, and finally, displays the image and name of the species on the screen.

Vasanthi, my hostess, interrupts my investigation to remind me that breakfast is ready. She is full of energy, getting ready for a busy day at the school where she teaches. Ravishankar, her husband, is waiting to explain the day's schedule, which includes a visit to the Kalamandalam, an institution founded in 1930 by the poet Vallathol Narayana Menon. Over the years, the school has become one of the main centres for the study of classical Indian arts, particularly Kathakali and Mohini-Attam.

After a delicious breakfast, we set off to Cheruthuruthi, an hour’s drive away. Nestled in lush surroundings, the institution comprises several buildings and the classrooms reverberate with the sounds of dance music, footworks of different styles and the rhythms of various percussion instruments, all under the guidance of an experienced master called asan in Malayalam.

I am always overcome with emotion when I hear the resonant chenda drums, played vertically with slightly curved sticks, used to inform the villagers that a Kathakali performance would be taking place that evening. Because of its powerful sound, it is an integral part of religious processions, cultural festivals, and social ceremonies in Kerala.

The visit continues, and in each classroom, memories of nostalgia and gratitude come flooding back. Everything in this environment is familiar and reminds me of my years of discovering and learning Kathakali theatre and classical Mohini-Attam dance, which for me were more than just artistic practices but also a cultural and spiritual experience.

One day, fate led me unexpectedly to Kerala, where at dusk in village temples, actors in magnificent costumes mime mythological tales by the light of oil lamps. In this traditional theatre, hands greet each other, touch each other, challenge each other, transform into fish, birds, merge to form the hood of a cobra. Sometimes the curled fingers become the claws of a tiger or the hooves of a horse. Kathakali struck a chord in me, awakening my curiosity and admiration for this unique form of theatrical expression.

I was instantly drawn to the symbiosis of dance, theatre, music, and mudra; this silent language that narrates epic and mythological stories, conveying complex emotions and deep cultural values through hand gestures. In Hindu rituals, the priest, like a storyteller, also addresses the divine, his fingers devoutly shaping the sacred formulae to invite the deities to manifest in a geometric diagram or in an ephemeral painting called a kalam in Kerala.

The main morning session of Kathakali brings together dancers, singers, and musicians. This exercise, known as choliattam, is designed to prepare students for public performance. They rehearse roles or dance sequences and practise improvisation.

As I continue my visit, I am greeted this time by the sound of the maddalam. This imposing cylindrical drum, worn around the waist, has a slightly curved middle section and is played with the hands. Every morning, students learn rhythms based on the exact wording of the bol, a succession of syllables whose sounds and accents correspond to sequences.

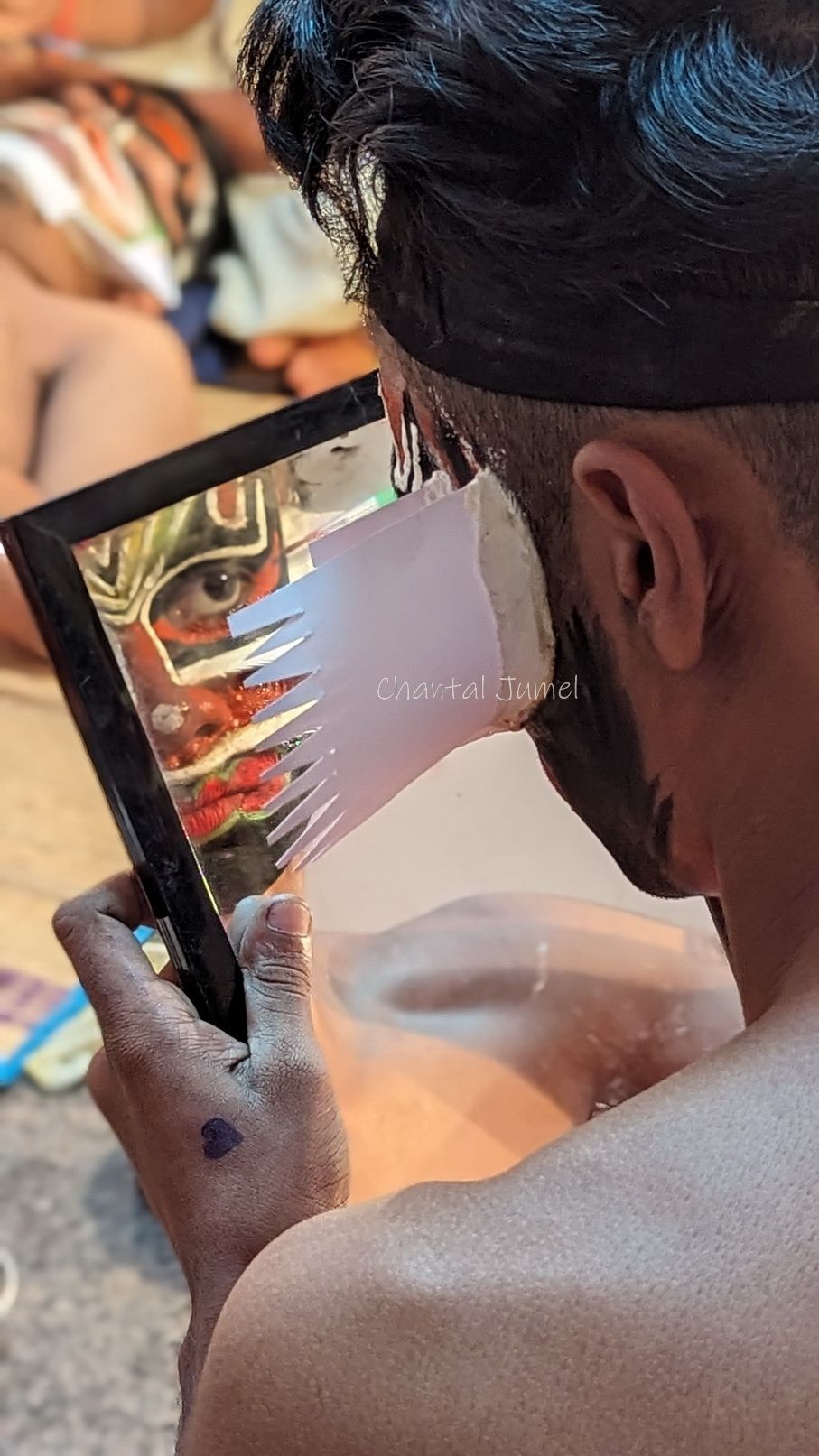

This mnemonic system is also used by the dancers, who memorise all choreographic sequences. Elsewhere, groups of students are divided by speciality; three young girls vocalize to the beat, while future make-up artists learn the lines and colours of each character category, as well as the art of layering white paper cut-outs over prominent facial features to create the illusion of a mask.

To conclude our visit to the school, we pay our respects at the tomb of poet Vallathol, the founder of the institution, before entering the gallery of portraits of the most illustrious actors who have contributed to the preservation, promotion, and enrichment of Kathakali.

Kalamandalam Krishna Nair was one of my teachers, and I will always be grateful to him for his invaluable teaching, storytelling skills, and understanding of human emotions. His presence and charisma will forever be etched in my memory.

I leave moved, carrying with me a spark of this radiant legacy. Tomorrow, a humble village temple will welcome the presence of the hunter-god Vettakkorumakan, a deity dear to the people of this part of Kerala.

Story to be continued...

Previous article:

Kerala Kalam, "On my way to the village of Paruthipulli" — part 1