Vrindavan Sanjhi , "A tradition shrouded in mystery." — part 2

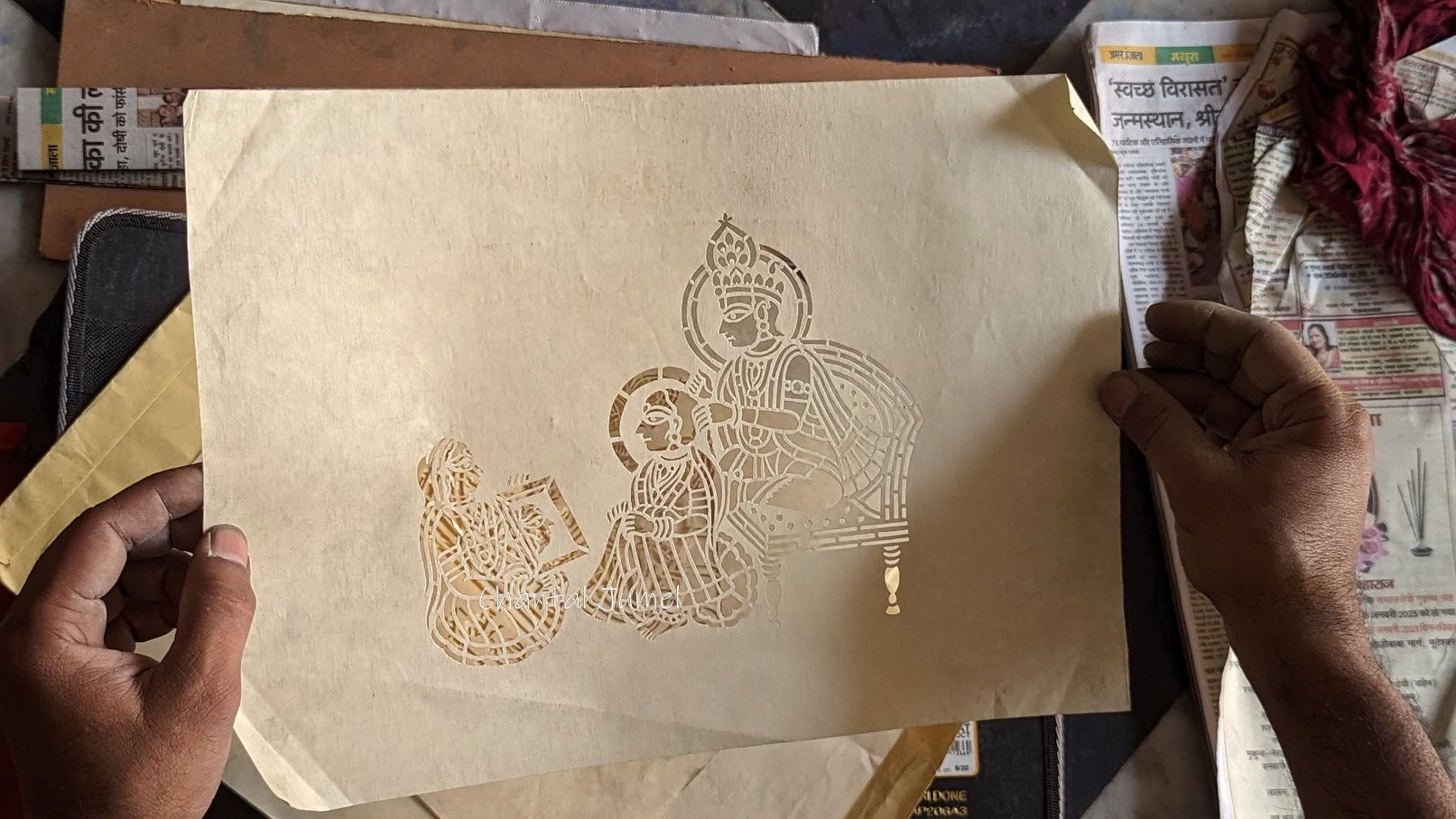

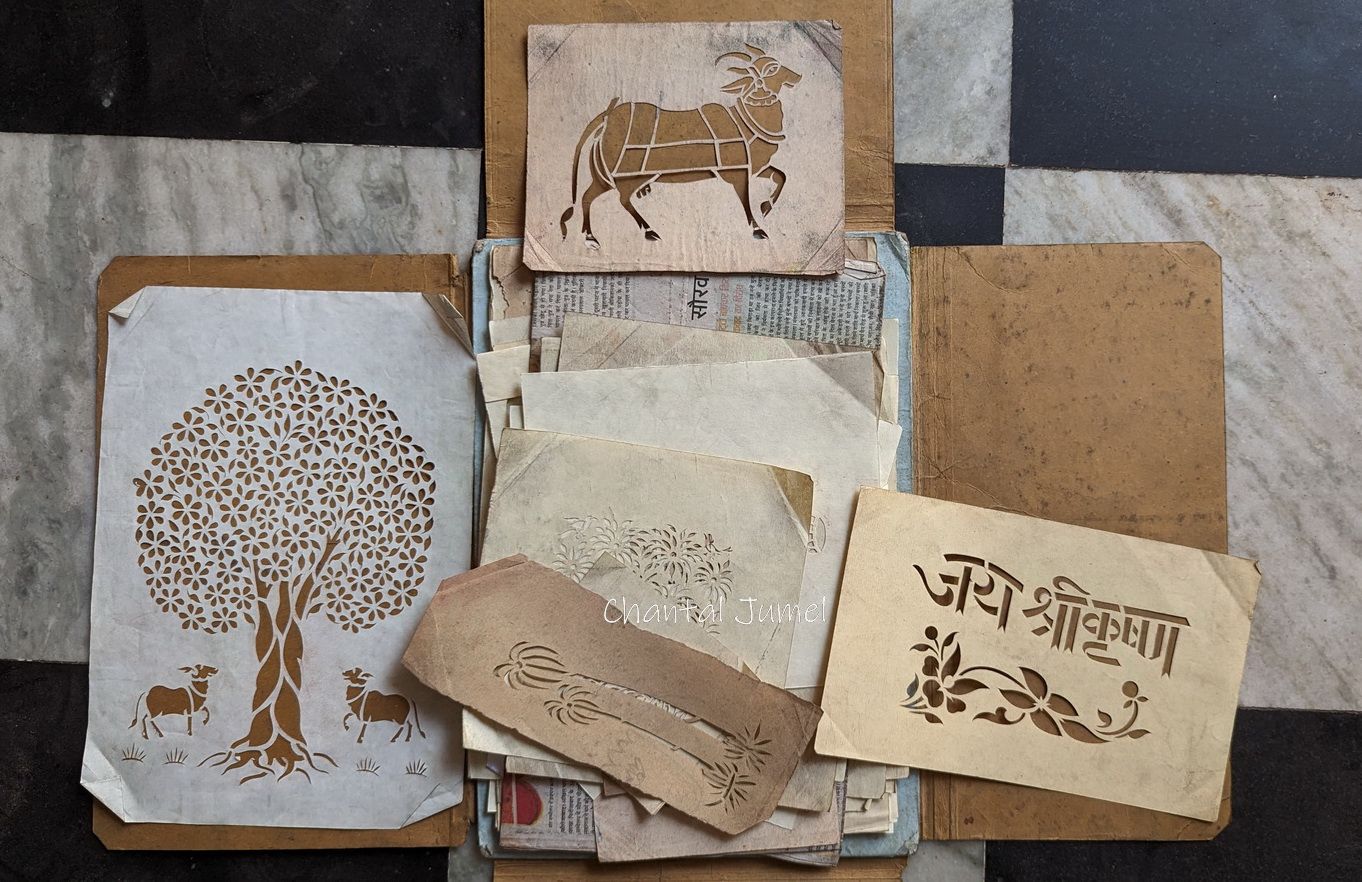

Unlike other floor paintings traditions in India, these are, to my knowledge, the only ones to be created using handmade paper stencils and coloured powders.

The ephemeral images created in the temples of the Braj region, and in particular in the Radha Raman sanctuary in Vrindavan, are unique. Unlike other floor paintings traditions in India, these are, to my knowledge, the only ones to be created using handmade paper stencils and coloured powders.

The origins of this pictorial tradition are shrouded in mystery. What is known is that sanjhi have their roots in the folklore of Uttar Pradesh and that they became a votive art when the devotional or bhakti religious currents that emerged in southern India gradually spread to northern India. Popular belief has it that it was the beloved Radha who initiated the practice of sanjhi by composing floral carpets to invite and impress Krishna. Another version attributes the origin of sanjhi to Lord Krishna, who created flower carpets in the evening to appease Radha's presumed anger. Feigned anger was part of the divine couple's love games.

It is also known that sanjhi were practised by members of the Madhva-Gaudiya sampredaya sect, one of the four main schools of Vaishnavism in 15th-century India, which flourished in this region at the time. Vaishnavism is one of the three main schools of Hinduism, the other two being Shivaism and Shaktism, which focus on the worship of the Mother Goddess as the source of universal energy. These religious currents are subdivided into schools or sects, and the ritual painters of the Braj region belong to the line of spiritual masters who are followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, the Hindu philosopher and reformer born in 1486.

At the heart of his teaching, he encouraged total devotion to Radha and Krishna, whose mutual love is a constant source of delight, and urged devotees to surrender to the Lord of Vrindavan, a path he considered more meritorious than others, as it favours emotion over scriptural knowledge. It is said that the melody of a flute was sufficed to plunge the philosopher into ecstasy. He was known for organising dance-dramas inspired by episodes from the life of Krishna. These intensely emotional manifestations of mysticism contributed to Chaitanya's popularity, as he wandered the streets alongside devotees from all social classes, chanting the divine names.

During my stay in Vrindavan, I was able to gauge the extent of this mystical exaltation. Although I was concentrating on photographing the creation of a powder sanjhi in the premises adjoining Sri Radha Raman temple, I visited the sanctuary several times during the worship ceremonies (arati) to soak up the effervescence that reigned there. What a difference with the temples of southern India and their more measured daily rituals! Here in Vrindavan, the devotees dance and sing in chorus, accompanied by musicians playing cymbals, drums and the harmonium.

The chants are regularly punctuated by the repetition of the names of the divine lovers Krishna and Radha and the clapping of hands. The devotees, enveloped in the fumaroles of incense and camphor, grab the flowers garlands that the priest sends out into the crowd and enjoy the collective joy of sharing what resembles divine intoxication, embodied by Radha the Beloved and Krishna, the eternal source.

It was against this backdrop that ritual painters transposed the amorous games of God Krishna and his beloved Radha into sanjhi paintings. My interlocutor Sumit Goswami comes from this religious tradition. He belongs to an illustrious lineage that, for more than sixteen generations, has always been dedicated to the service of Lord Radha Raman (another name for God Krishna), whose worship was entrusted in 1554 to their ancestor Gopal Bhatt Goswami, one of the six famous Goswami associated with Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. The votive art of Sanjhi has been an integral part of the rituals of the Radha Raman temple for many generations, and Sumit Goswami is its current representative. Since childhood, he has been interested in the many artistic traditions of his native region. After obtaining a degree in philosophy, he decided to devote himself to the art of sanjhi and its promotion outside the temple.

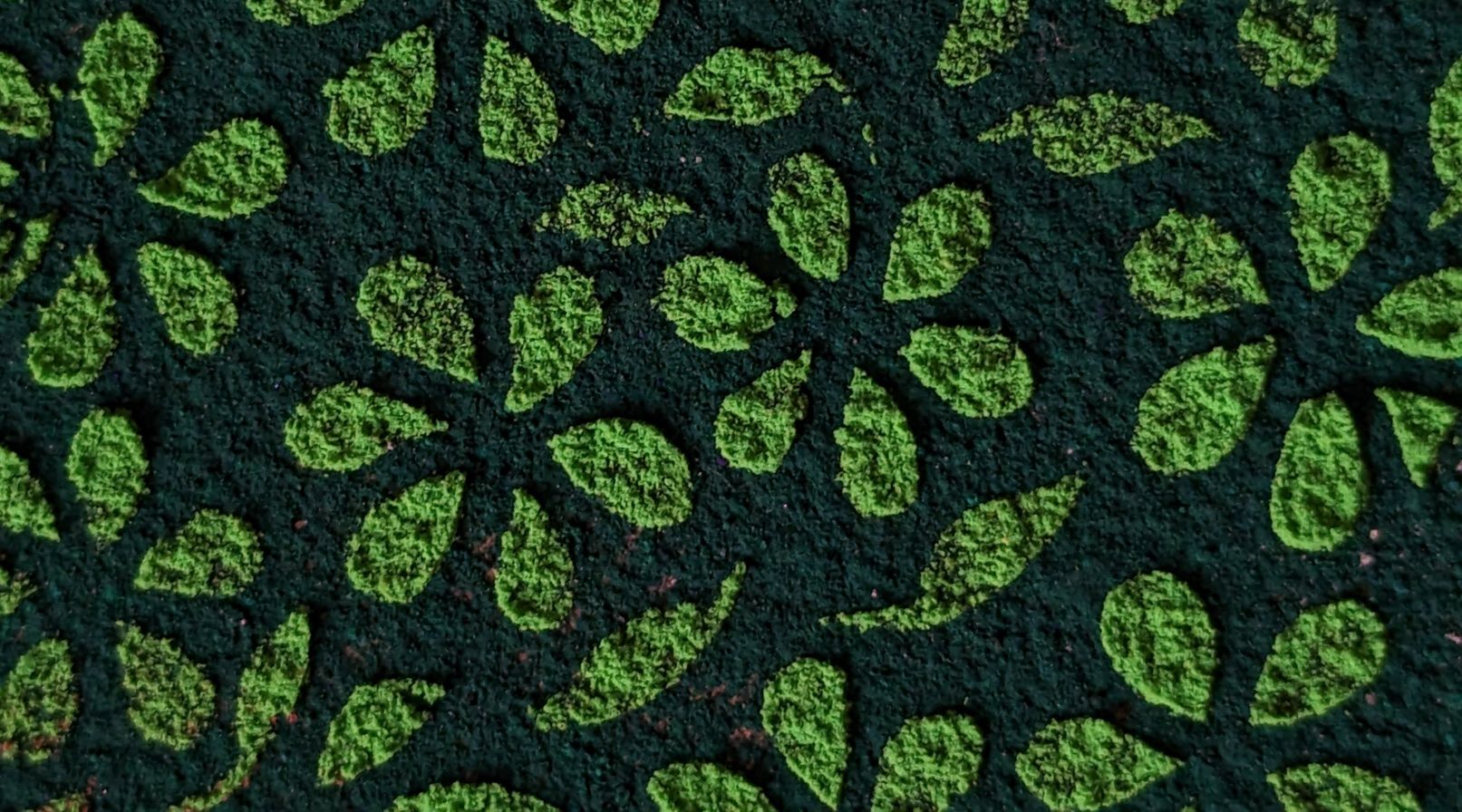

The festival of domestic and temples sanjhi is part of the same annual cycle as the period known as pitru paksha, dedicated to the ancestors to whom offerings are made. Sanjhi are created after the autumn monsoons, during the dark fortnight of the lunar month of Asvin (mid-September to mid-October). In general, the pitru paksha period is a time for reflection, conducive to spiritual exercises rather than revelry of any kind. The sanjhi festival is an exception, as according to the principles of the devotional philosophy of the Braj region, the celebration of the spiritual love of the divine couple Radha-Krishna transcends the limits of the phenomenal and goes beyond the auspicious and the inauspicious. Sanjhi go further than aesthetic considerations, symbolising the joy of Radha and Krishna's reunion in the evening, after a long day of separation. In its popular and domestic form, the term sanjhi refers to "sandhya"or twilight and refers to an image made of cow dung spread on a wall or on the floor, then decorated with coloured stones, pieces of mirror and flowers, and worshipped at twilight by young unmarried girls in in the hope of attracting a suitable husband. The custom continues to this day in the villages of Braj and in rural areas of Rajasthan, Punjab, and Madhya Pradesh.

From the outer walls of a house to the earthen altar of a shrine, Vaishnava temples seem to have adopted, integrated, and transformed the domestic sacred images created by young girls into sophisticated religious images painted by men, which today form part of the liturgical rituals in a few temples in Vrindavan.

Story to be followed...

Previous article:

Vrindavan Sanjhi , "In the footsteps of Radha and Krishna" — part 1