Vrindavan sanjhi, "Stencil art to celebrate the divine couple Radha Krishna" — part 3

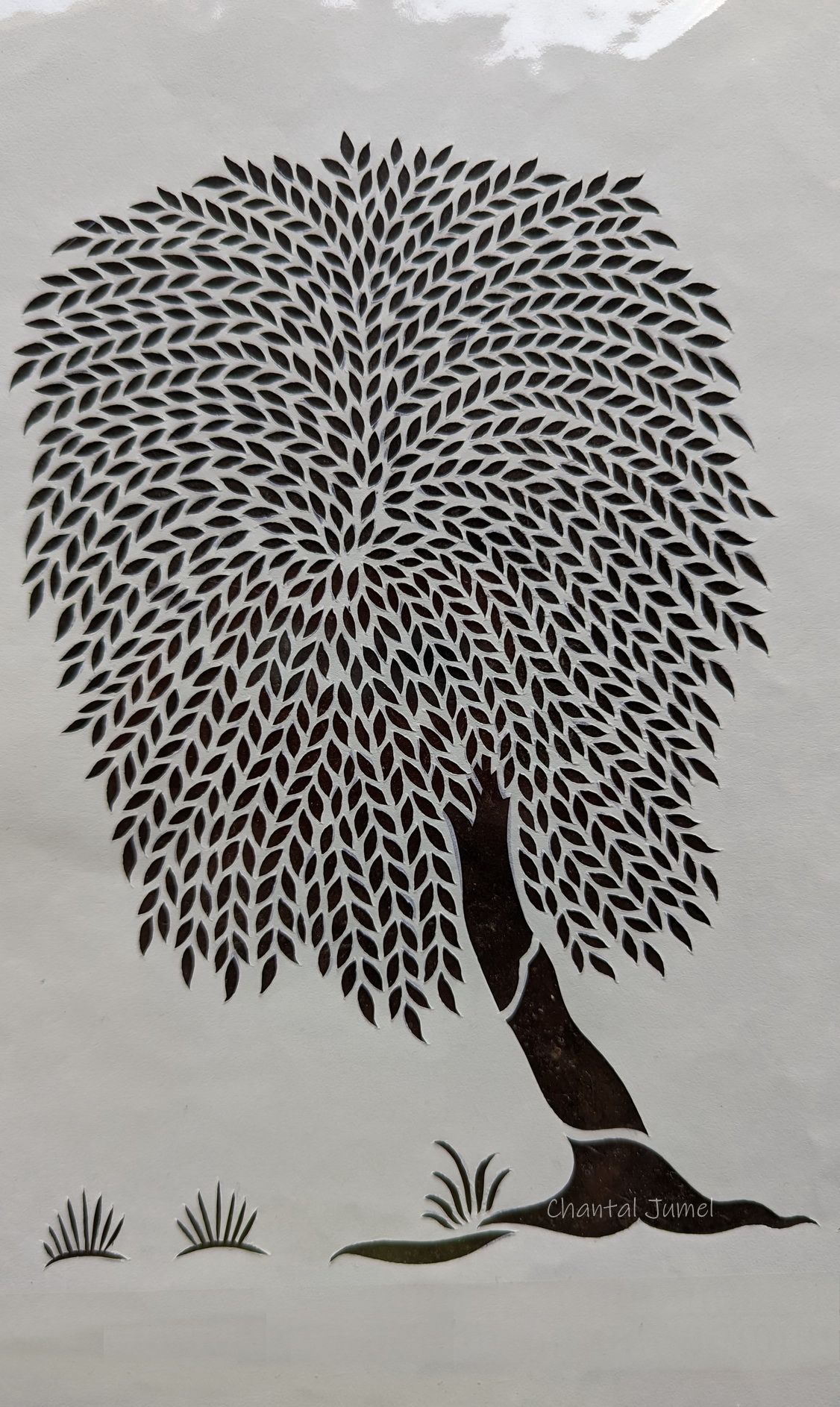

The beauty of sanjhi lies in the perfect precision with which the stencils are cut, and the skill of the painter in placing them one after the other without the design and background blurring.

Finally, there is little documentary evidence of the transformation and evolution of the domestic sanjhi into a sophisticated votive art elaborated by priests. It has also been suggested that the creation of the temple sanjhi on an octagonal platform called a vedi/kunda is linked to the ritual practice of decorating sacrificial hearths.

The sacrifice of fire (homa) is a fundamental element of Hindu rituals. Agni, the fire god, is the "mouth of the gods" and as the personification of the sacrificial fire, he is the bearer of the oblation and the messenger between humans and the divine. During religious ceremonies, women in Tamil-Nadu decorate the hearth with kolam, just as the sanjhi decorates the raised platform known as the vedi.

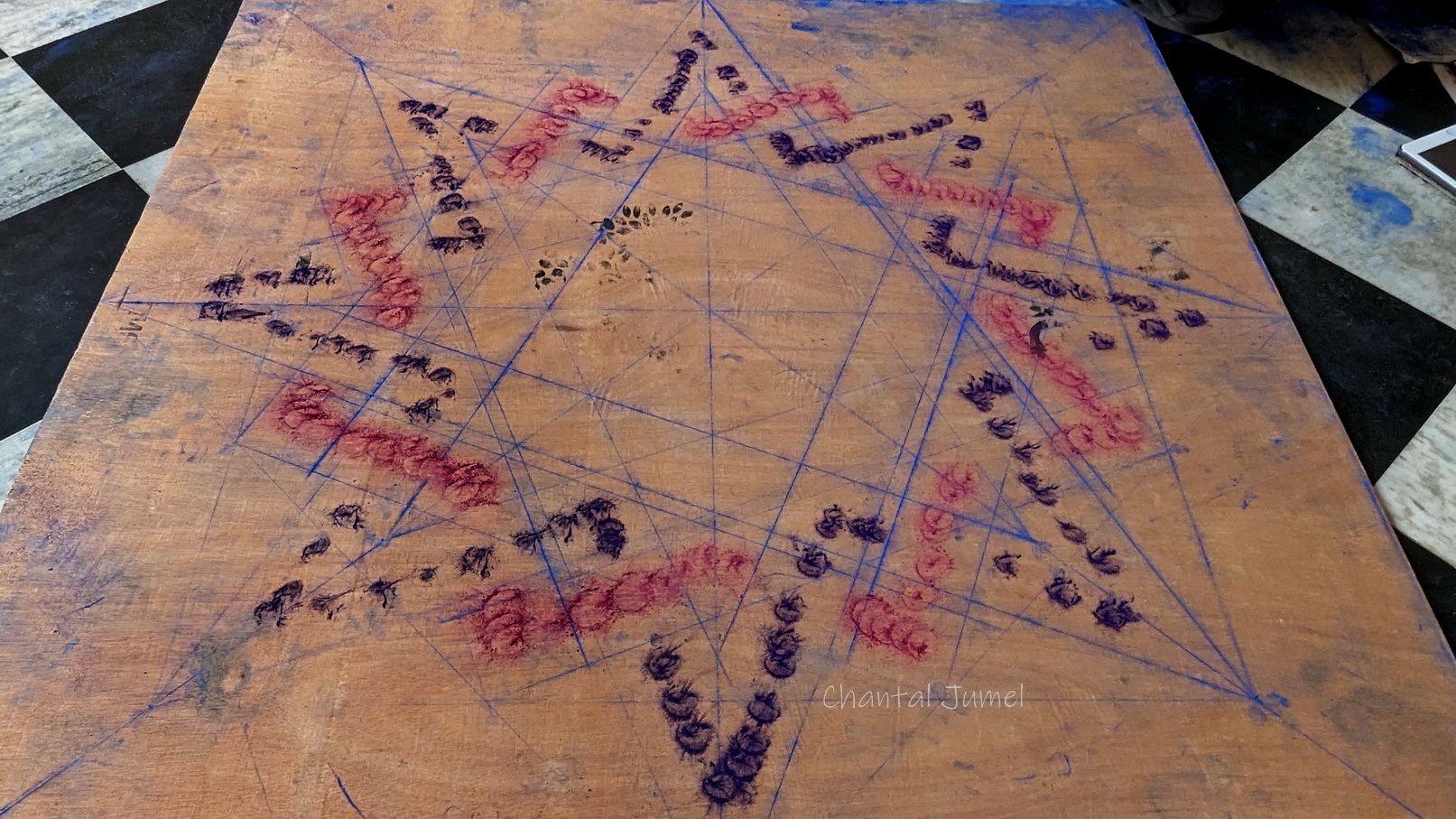

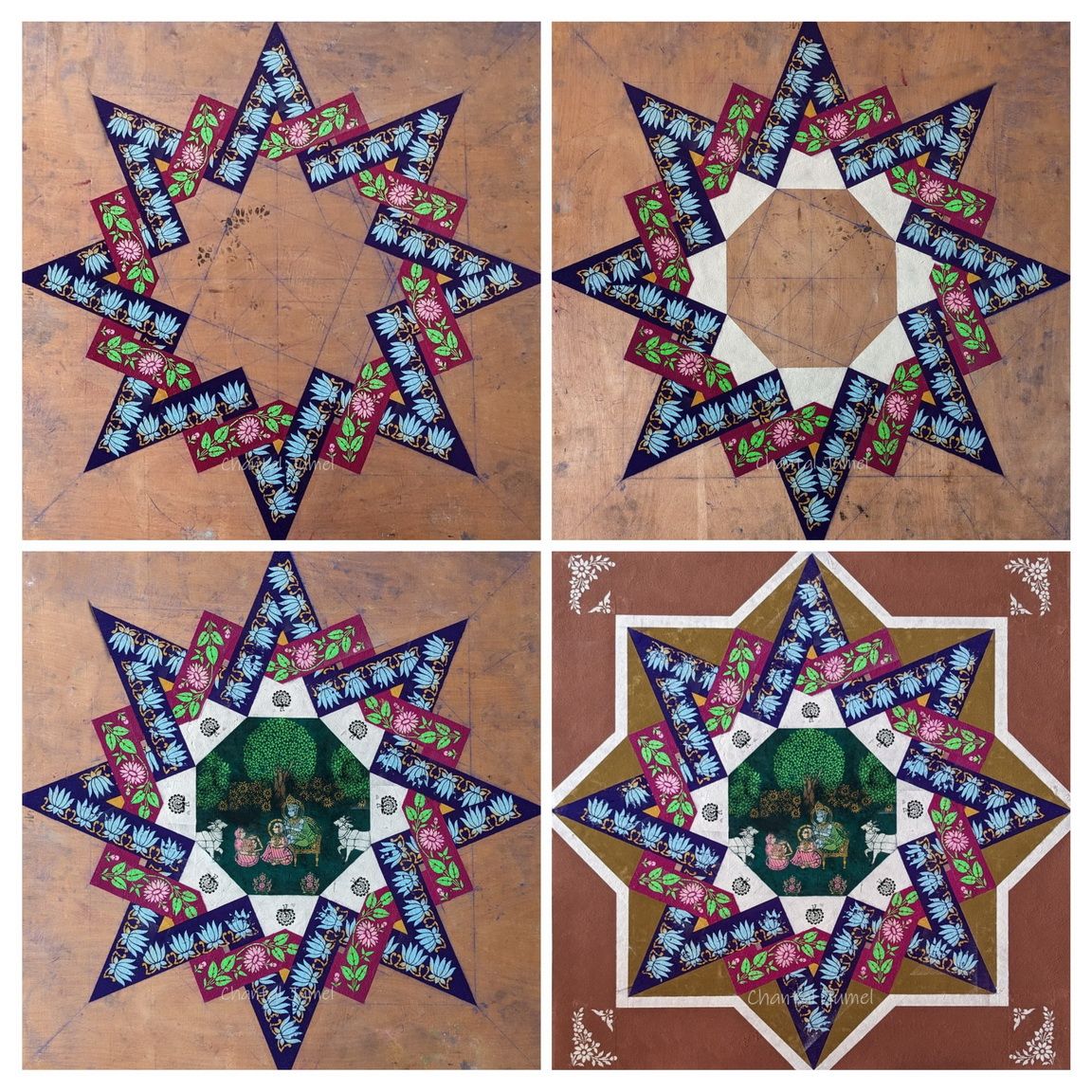

The two superimposed squares on the platform are also reminiscent of the yantra, geometric diagrams devoid of any iconographic representation and designed as a support for meditation on a personal deity or as tools for representing and visualising divinities. In sanjhi art, the star-shaped clay platform is made up of two superimposed squares symbolising an eight-petalled lotus. The clay is the same as that used to make quality bricks. It must be sand-free to ensure that it is solid and does not crack during the building process. The finished platform is 20 cm high, with perfect plunging edges, and it is on this dedicated surface that the ritual painter draws the sanjhi, and not directly on the floor as is the case with other forms of ephemeral drawings or paintings in India.

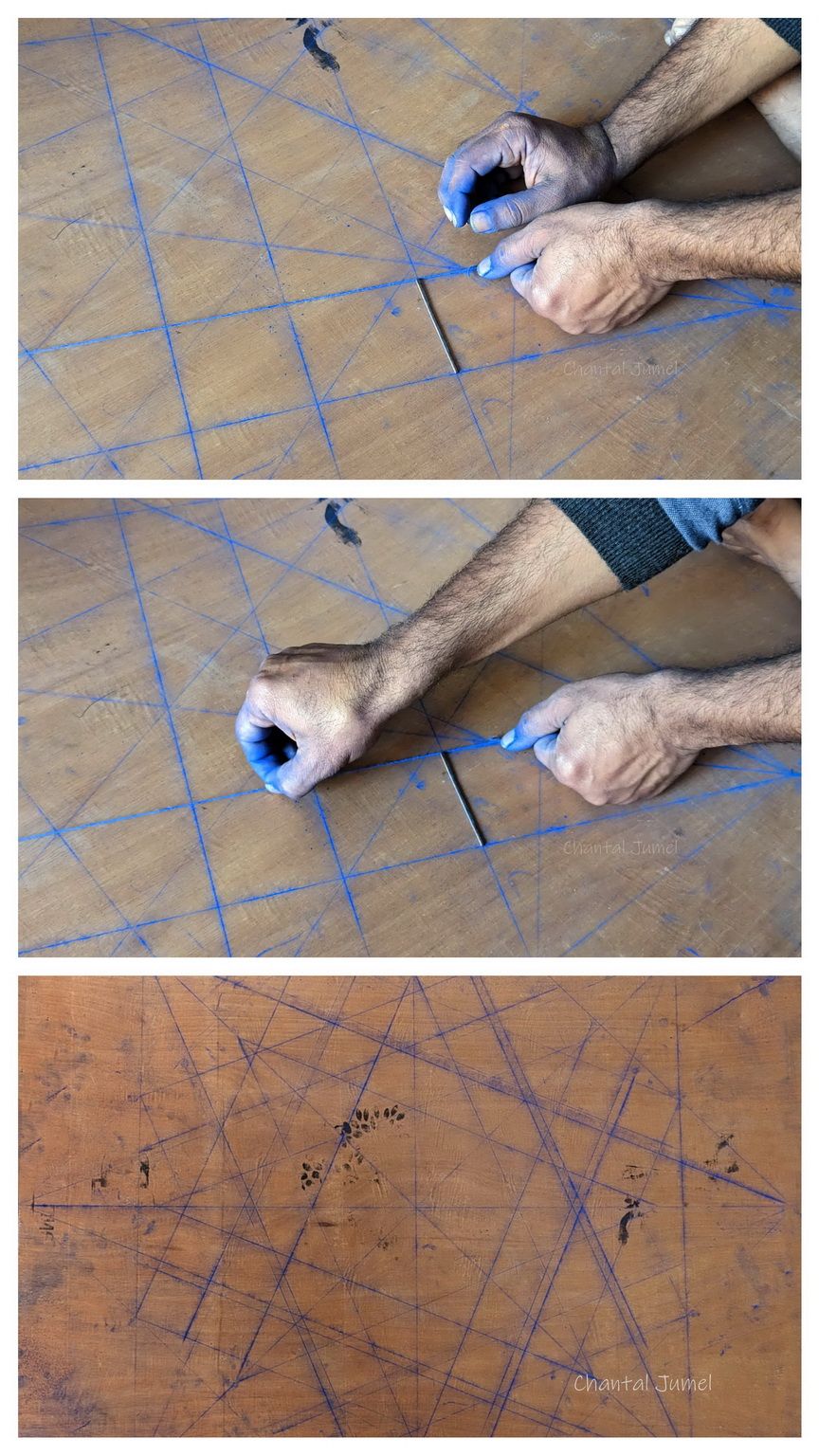

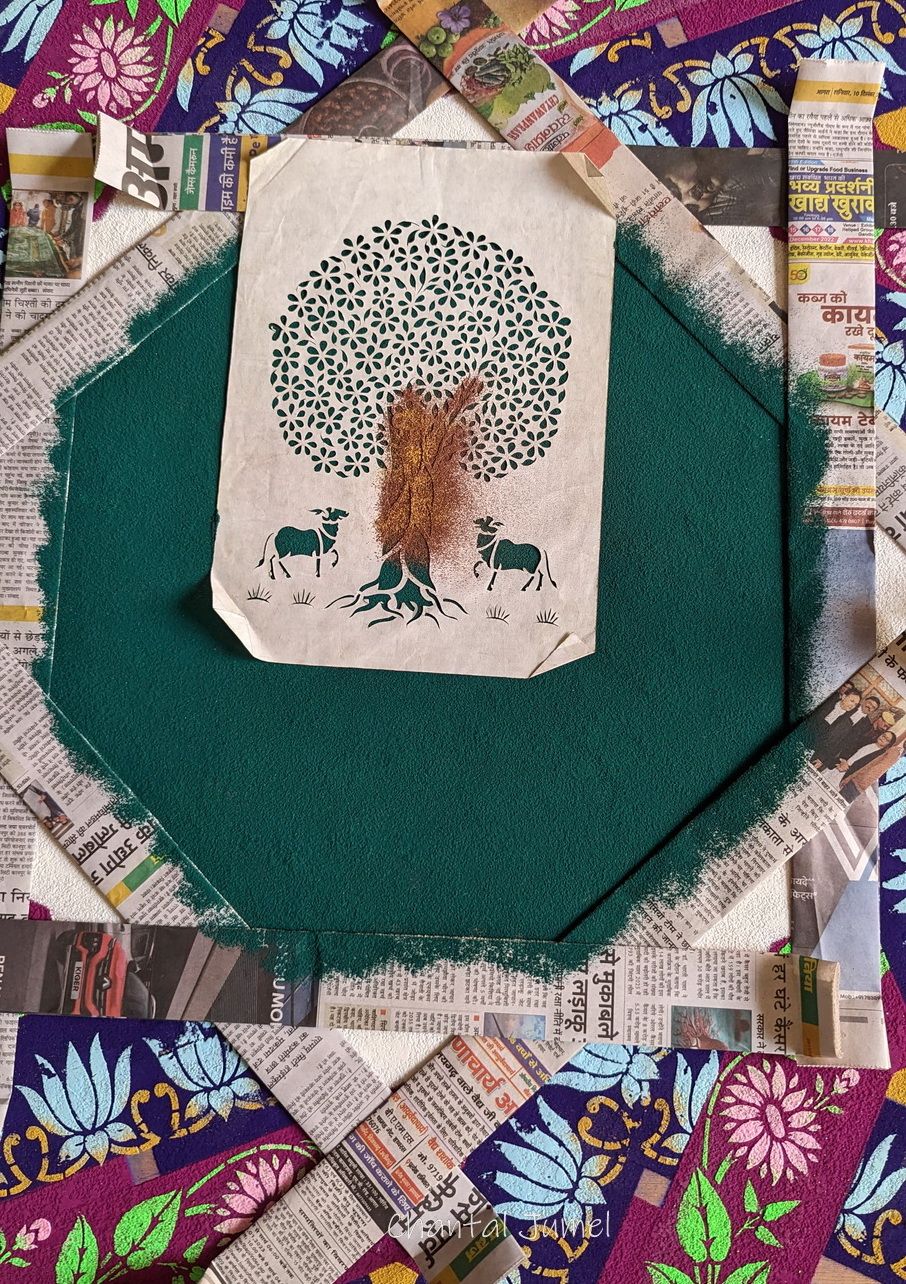

For the purpose of my documentation, the painter used a chipboard panel, as the making of a sanjhi in the temple is traditionally done out of sight and no-one apart from the priests is present during its creation. To perfectly delineate the contours, he uses a simple string as a tracing line and blue powder to mark and divide the space into various sections. Then, by pinching the string, the tracings appear and form the lines of the drawing.

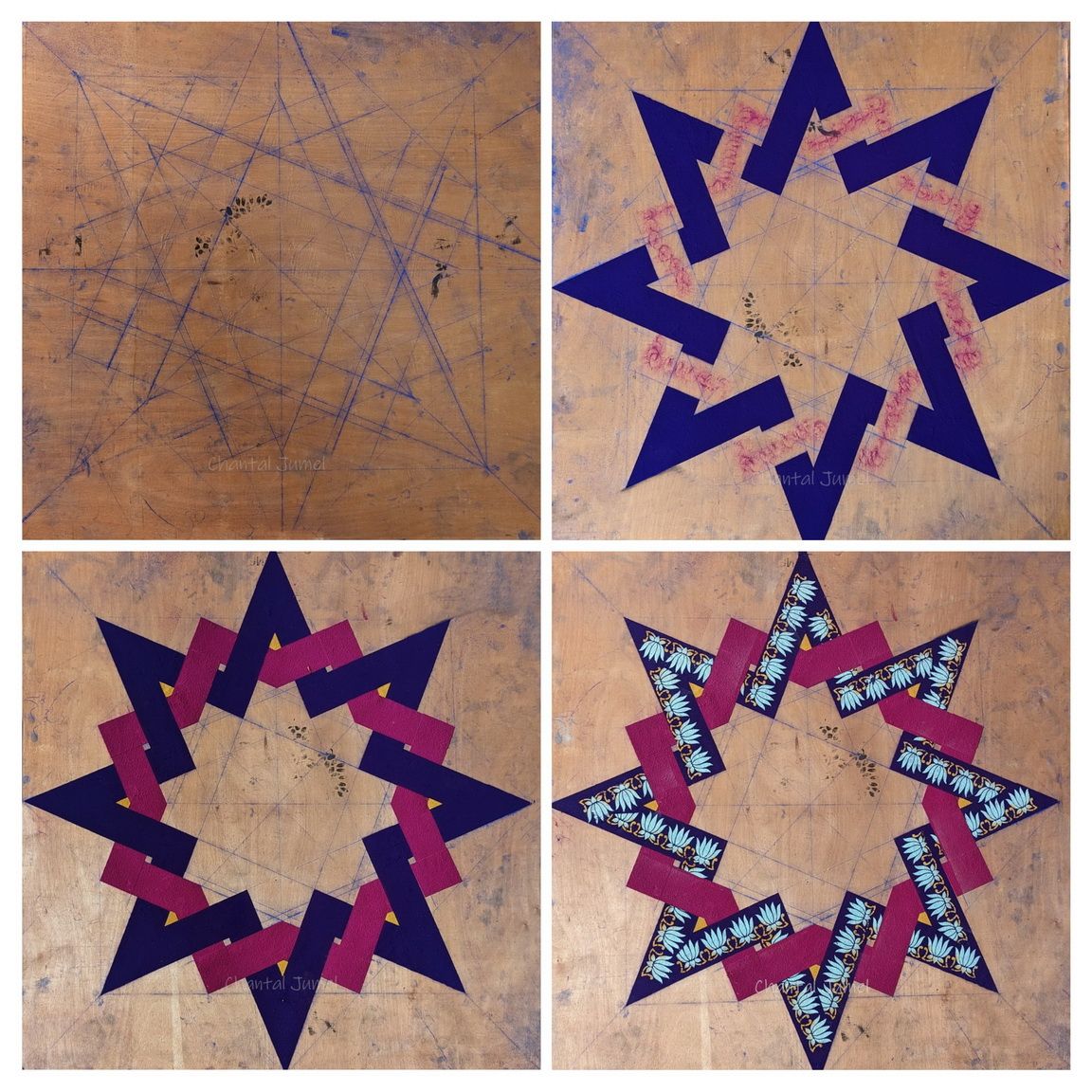

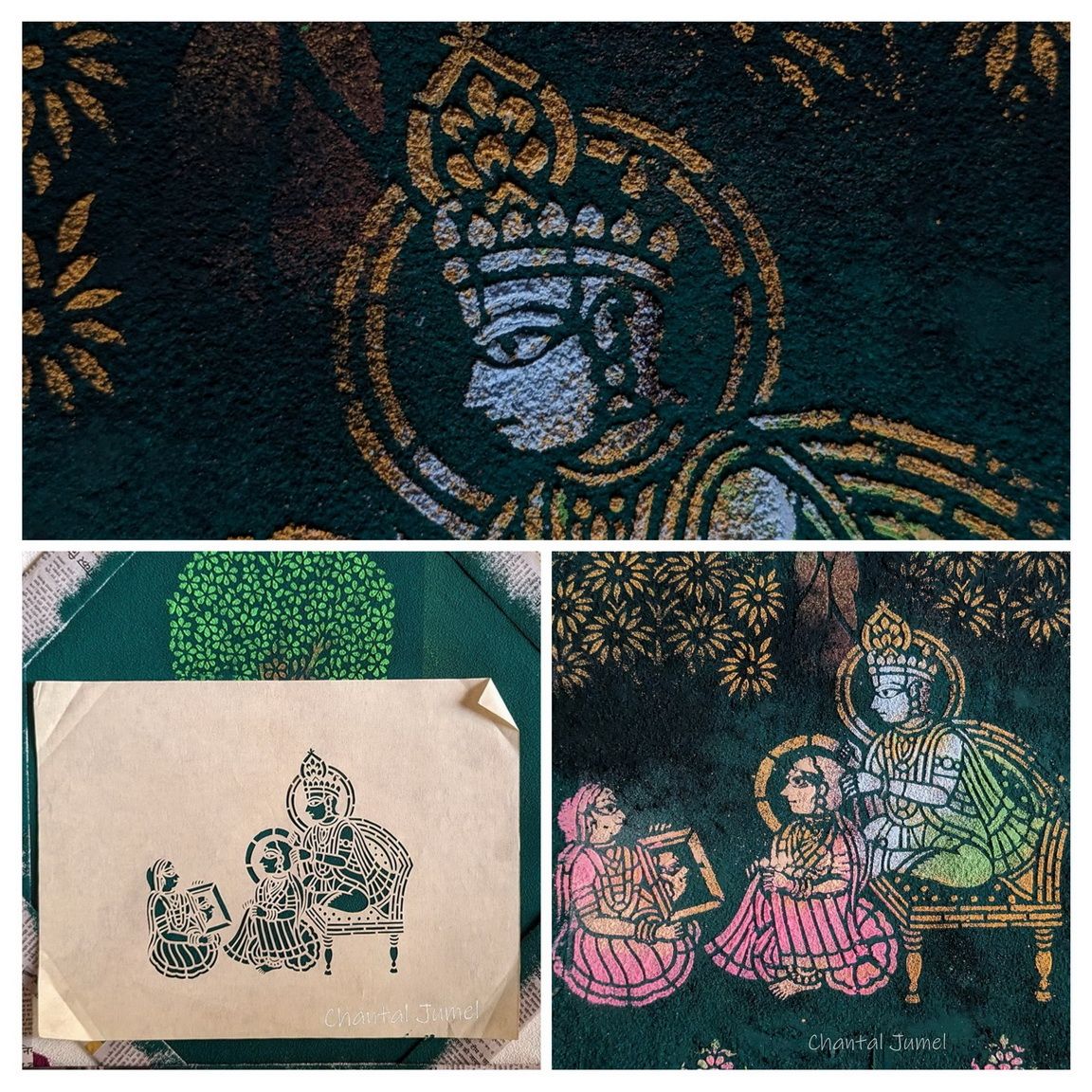

He then stamps the outer stripes roughly with two distinct colours. Only an experienced painter will be able to decipher the subtleties of alternating over and under the ribbons, and through the magic of stencilling, patterns of flowers and leaves appear on plain backgrounds.

Once the network of lines has been set up, the votive images are created using stencils cut to the desired pattern, and the exposed areas are powdered with colours using a fine muslin or a sieve. The operation is then repeated with other stencils on a background colour.

The beauty of sanjhi lies in the perfect precision with which the stencils are cut, and the skill of the painter in placing them one after the other without the design and background blurring. The stencils are cut using long-handled scissors with perfectly sharp blades. To lift the stencils without altering the powder, the ends of the paper are turned upwards to make the task easier. I wonder about the origin of this technique. Are they related to Chinese or Japanese paper cut-outs? No one has an answer. Flipping carefully through the stencils in Sumit Goswami's folder, I see trees filled with birds and fruits, various patterns of flowers, foliage and climbing plants, paper cut-outs featuring animals including elephants and monkeys.

Cows hold a special place in sanjhi, often appearing with one foreleg in the air, as if stopped in their tracks and mesmerised by the vision of the divine couple Radha Krishna, who always occupy the central medallion of a sanjhi painting.

The backgrounds are manifold: temple towers, low walls, balustrades, swings, palanquins, oil lamps etc. By combining colours and stencils, the sanjhi takes shape after several hours of painstaking work.

The central medallion always depicts episodes from Krishna's life and scenes of love in the company of his beloved Radha. Every evening, during the last 15 days of the lunar month of Asvin (mid-September to mid-October), the sanjhi are made, worshipped, and displayed to the devotees before being immersed in the water of the sacred river Yamuna.

The presentation of the sacred artwork in the temple is always accompanied by devotional songs celebrating the importance of gathering forest flowers to create a sanjhi. Vaishnava literature contains specific repertoires that are always linked to Radha and her flower-picking friends or to the atmosphere of the festival. Some scholars believe that the village ritual of sanjhi performed by young girls influenced the poetry of the Braj region, and that verses celebrating flowers and the world of plants contributed to the aesthetics of the sanjhi in the temples of Vrindavan, which abound in floral interlacing around the central medallion portraying the divine couple.

Jal sanjhi, painting sanjhi on water

In addition to the sanjhi drawn on a platform, there are floating sanjhi done with powders in a shallow dish filled with water. These sanjhi require greater skill if the colours are not to sink to the bottom of the dish.

This delicate graphic variation is said to have been inspired by a legend according to which Radha, having seen the reflection of God Krishna on the surface of a pond, wanted to frame it with flowers. Since then, ritual painters have been creating images on water to honour Krishna. Others believe that the water is a symbol of the river Yamuna, where Krishna played as a child and teenager, and the floating sanjhi are a mirror of his life. After evenly powdering the surface of the water, the ritual painter carefully places the stencils one by one and colours the cut-out areas in accordance with the scene he wishes to create.

Although I was fascinated by Sumit Goswami's talented demonstration, it lacked the excitement and fervour of a religious festival and I hope to be able to return at this time of year, during the 15 days when the divine images are presented to the devotees each evening, accompanied by devotional chants.

Story to be continued...

Previous articles:

Vrindavan Sanjhi , "In the footsteps of Radha and Krishna" — part 1

Vrindavan Sanjhi , "A tradition shrouded in mystery." — part 2