How it all began

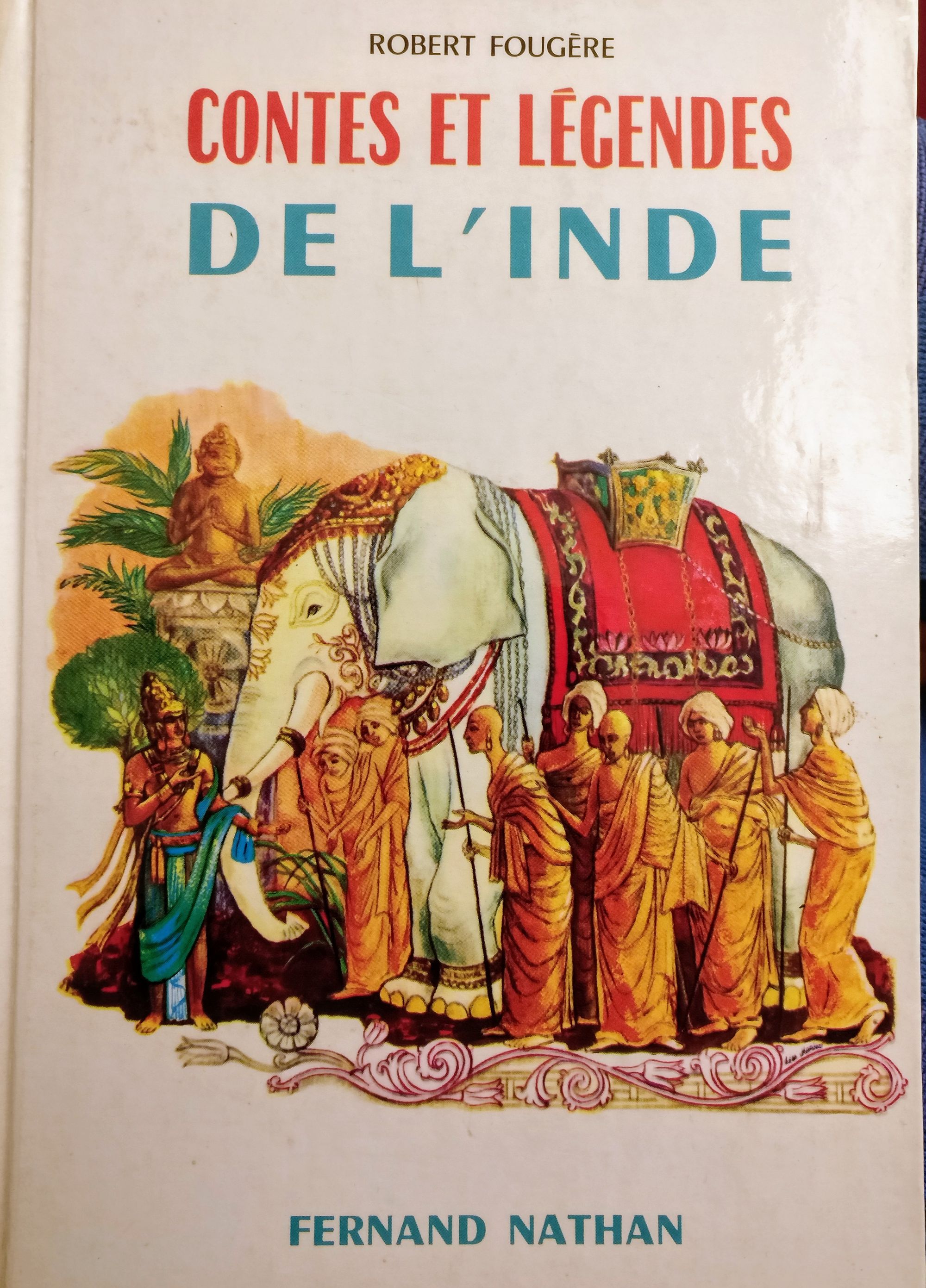

As a child I dreamed of becoming a dancer or an actress, a musician or a painter, and my favourite book was “Contes et légendes de l’Inde”. The images showed black and white men in turbans, an assembly of bonzes, a man with an elephant face and characters with numerous arms and heads.

From "Contes et légendes de l'Inde" to the film "The River" by Jean Renoir

As a child I dreamed of becoming a dancer or an actress, a musician, or a painter, and my favourite book was “Contes et légendes de l’Inde”. The images showed black and white men in turbans, an assembly of bonzes, a man with an elephant face and characters with numerous arms and heads. Among them, there was an attractive figure, a young man with mysterious almond shaped eyes playing a flute. It fascinated me without a reason, and it was only after several pages that he reappeared and this time in colour illustration; his skin was blue, and the headdress conferred him a princely appearance. His name was Krishna, and the story of his exploits was going to occupy most of the book and part of my life. Another coloured image showed a blind king on a battlefield; the blazing background suggested blood and a fiercely, mercy less battle. The earth was strewn with broken spears, defeated elephants and lamenting women holding out their arms. This brutal evocation, threw me into the world of Mahabharata, one of the greatest epics of India.

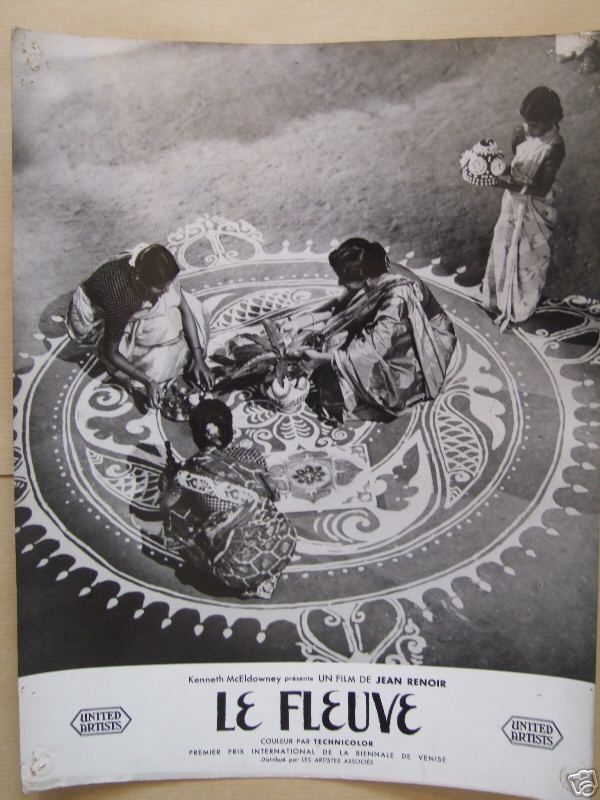

Krishna, the valiant prince, the youthful cowherd playing the flute, I was going to meet him again in the legendary film of Jean Renoir called “the River” which was shot in Bengal. In a scene, one of the heroines imagines herself to be Radha, the beloved of the dark-skinned god for whom she dances addressing him praises through hands gestures. The dance episode as well as the opening scene of the film were to impress permanently the course of my existence.

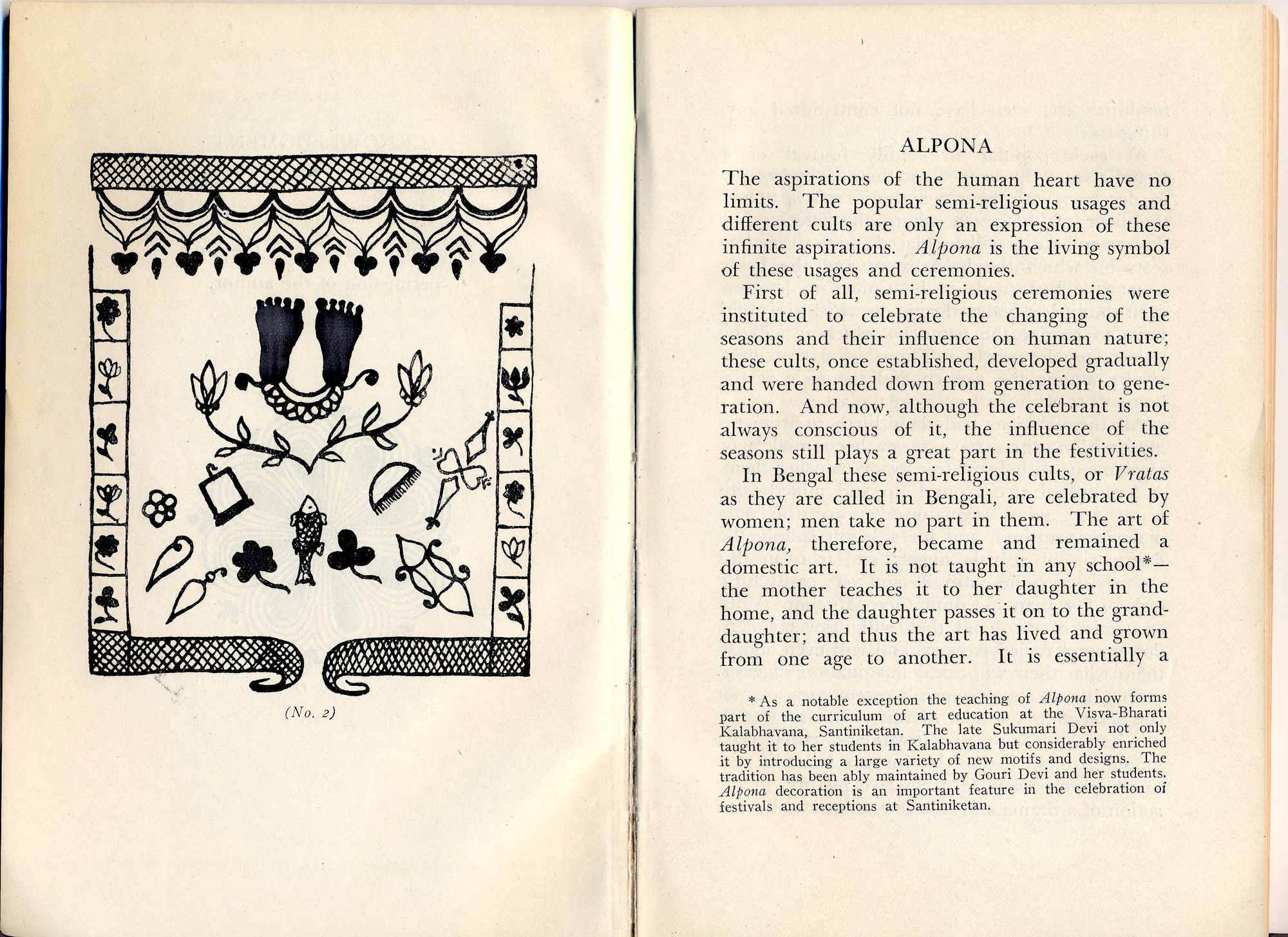

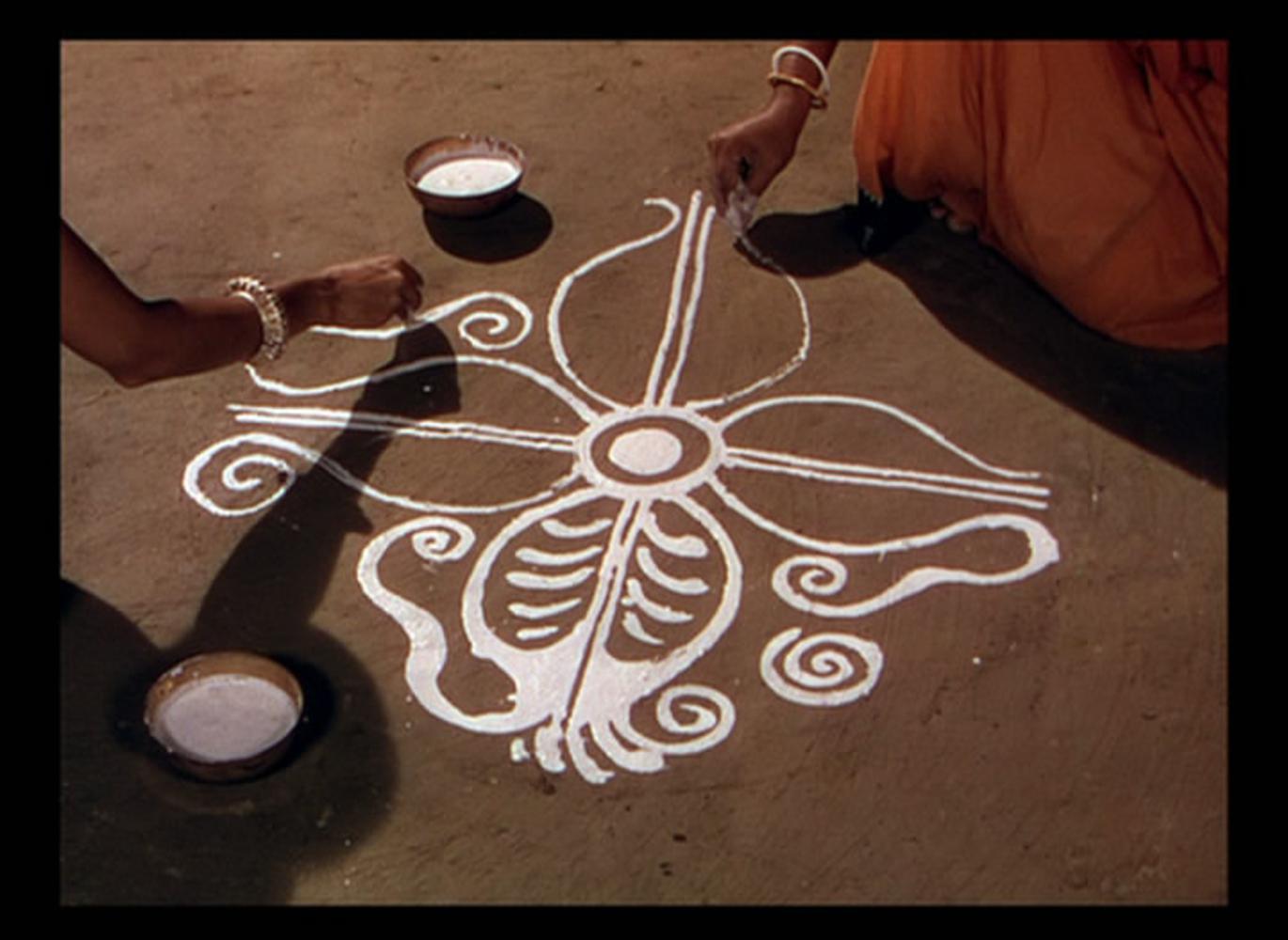

The very first image that Jean Renoir offers to the audience is the sight of a feminine hand tracing a perfect white circle on the ground, followed by four petals facing the cardinal points while an off voice starts narrating the film: “In India to honour guests on special occasions, women decorate the floor of their houses with rice flour and water”. What an appealing custom, the gesture and the sitting posture are fascinating but why paint on the ground? Is there a reason? Is there a repertory or is it merely the result of a fertile imagination? Does the painting remain? The questions lingered in my mind for a long time until I decided to go to India.

Then I read “L’Alpona ou les décorations rituelles du Bengale”

After watching Jean Renoir’s film «The River», I wanted to find a book that would describe the astonishing drawing gestures seen at the beginning of the movie. One day, heading to the library of Asian Museum Guimet in Paris, I found a book titled “l’Alpona ou les décorations rituelles du Bengale” with illustrations from the painter Abanindranath Tagore and nephew of Rabindranath Tagore the poet, writer, composer, and Nobel Prize in 1913. Page after page, the booklet features geometrical diagrams, animals, birds, and everyday objects as well as descriptions of rituals. The former English version “Alpona” was written by Tapan Mohan Chatterji and published by Orient Longmans.