Jharkhand, "What future for Hazaribagh paintings?" — part 6

We must admit that these wonders of human creativity are fading away in the villages year by year. However, these tribal paintings, in their paper form, have travelled the world, giving rise to exhibitions or live performances in prestigious museums.

My stay at the Sanskriti Centre left me with a feeling of bitterness, not because of the quality of the murals I saw, but because they are becoming increasingly rare in the villages. This is borne out by the many photographs of the Imam family taken over the last twenty years, which show an abundance of painted houses and a varied repertoire. What are the reasons for this? Cited are: the Covid years; migration for work; and the displacement of tribal communities due to mining; the lack of naturally occurring pigments; and the replacement of mud houses by brick or cement houses, which are impossible to paint. I also noticed the absence of young girls painting, as if their mothers had stopped passing on the art because they did not see the point. One wonders why the younger generations seem to be losing interest in this exceptional patrimony. Is it the difficulty of embracing such a heritage at a time when their existence as Indigenous oscillate between identity claims, dispossession, integration and forced conversion under the guise of education?

A young generation struggling to identify with the codes and myths of their parents, with songs and poetry that tell of the forest and its animals, that speak of plants and trees as living beings, that marvel at a school of fish in the swift waters of a river, that rejoice at the fireflies that lit up the night as the boys dance. The environment has changed: the coal fields have devoured the jungle, left the land barren, driven animals, and birds to extinction, wiped out rare plants, mushrooms and flowers, and polluted the Damodar River. The stories, songs, and bucolic festivals may not mean anything to this generation. Many go to the city to study, while others are simply attracted to the urban world and dismiss these paintings as naive. This phenomenon is common in other parts of India and elsewhere in the world.

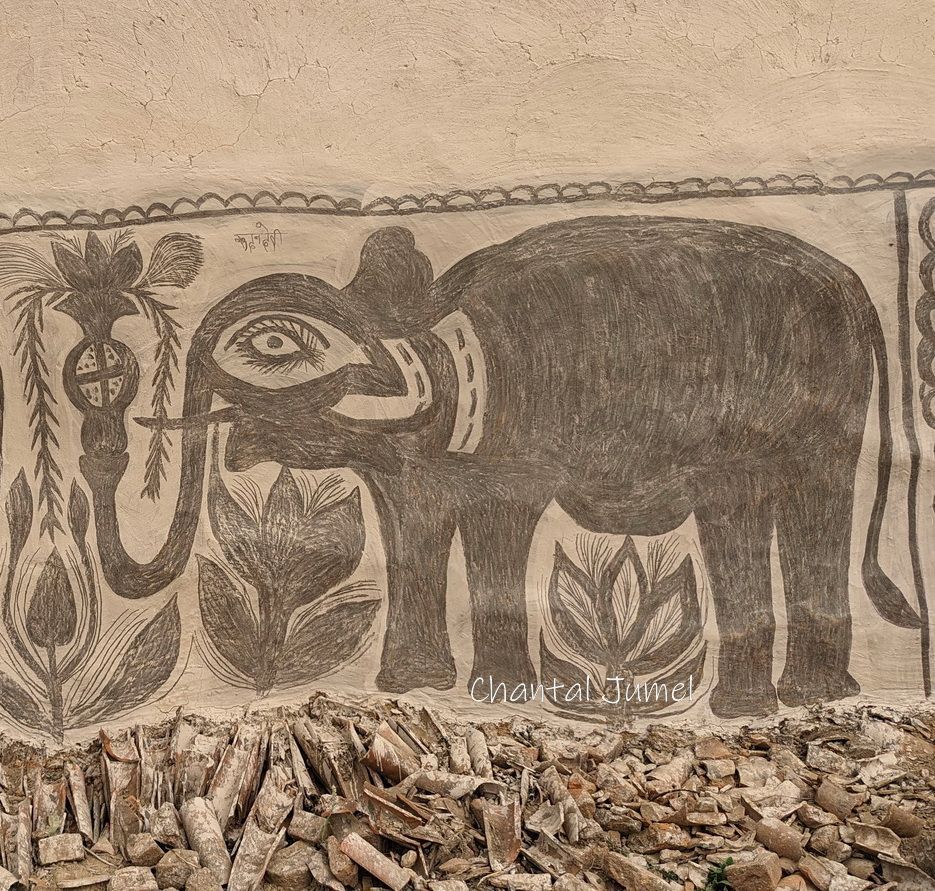

Hinduisation has brought changes, which are surreptitiously manifested when an elephant depicted in a mural becomes Ganesha, the elephant-headed god, while tribal traditions attribute other stories to him. Christianity, for its part, has opposed rituals dedicated to animist deities, the worship of trees, tattoos, men's jewellery, feather ornaments, and so on.

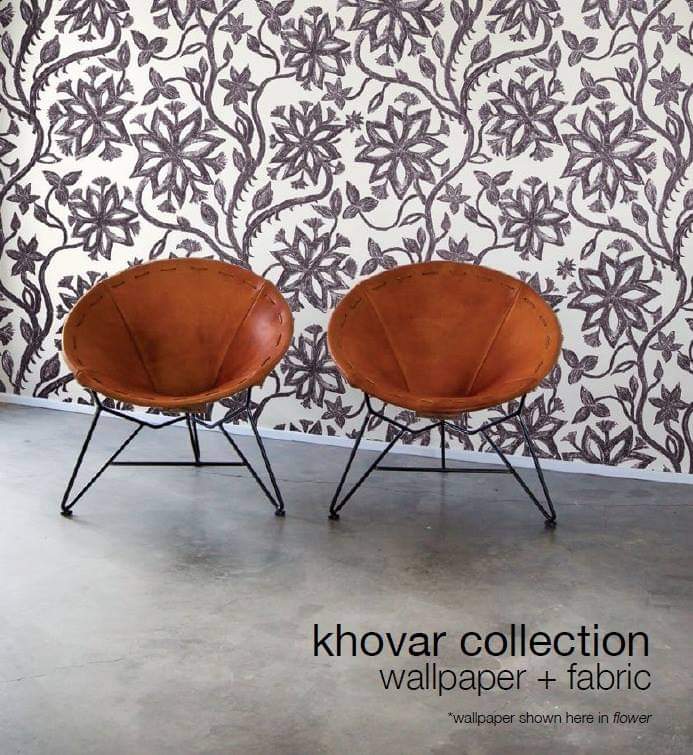

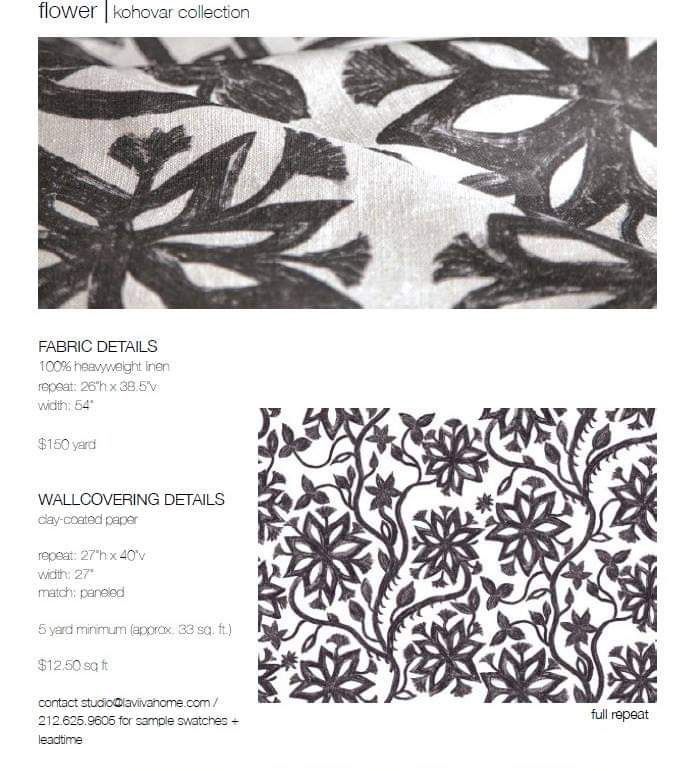

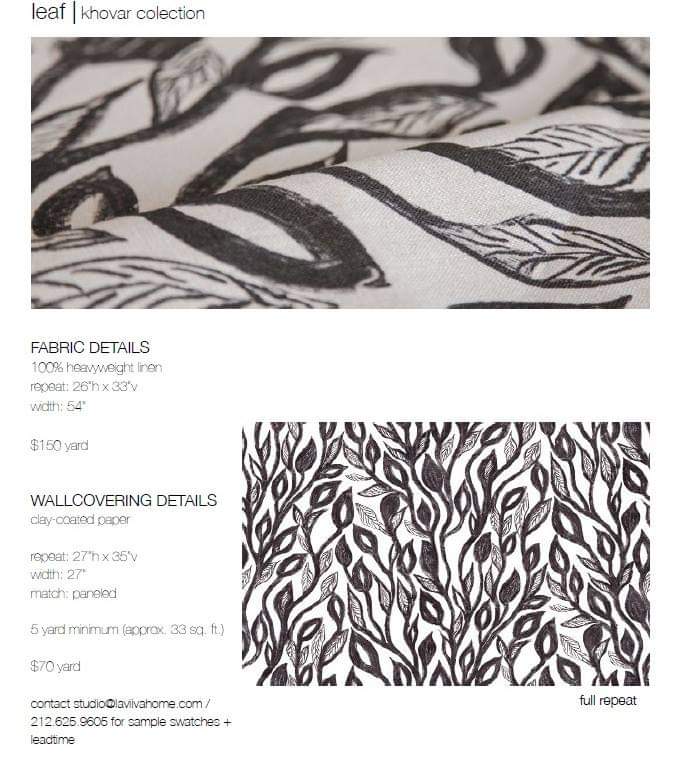

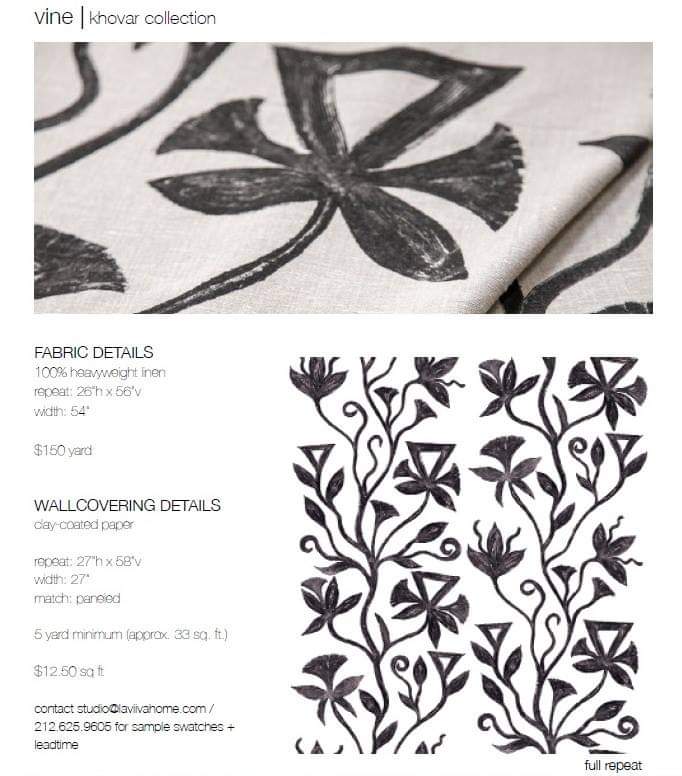

We must admit that these wonders of human creativity are fading away in the villages year by year. However, these tribal paintings, in their paper form, have travelled the world, giving rise to exhibitions or live performances in prestigious museums. Several articles published in interior design magazines (World of Interiors, AD India, Maison Marie Claire) and on the Wall Street International blog have testified to the interest and beauty of this heritage. Some of the motifs have been used on wallpapers and cushions sold by L'aviva Home in New York.

But these paintings need new media to survive, and one way to ensure the survival of this heritage is to encourage demand for them. Individuals through social networks, companies, institutions, and the government have this power. Recently, Justin's wife Alka Justin and their son Adam created a collection of saris painted with traditional motifs.

The association "Femmes du Hazaribagh", founded by Deidi Von Schaewen, is carrying on the work. Thanks to membership fees and other initiatives, the French association provides financial support for the purchase of pigments and materials, pays the women artists, and provides financial assistance for wedding expenses, for example. The funds also enable workers to be employed to maintain the Sanskriti centre. There are regional initiatives, such as the Hazaribagh railway station, which was painted in 2015. After Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighted this remarkable effort, it was the turn of all government buildings in the country to be painted with motifs inspired by local cultures. The idea was to turn railway stations into public art museums, making people aware of their cultural heritage.

A few days later as I was leaving the centre on my way to the airport, I came across a group of people waving a flag made up of red and white horizontal lines, which my guide called the Sarna flag. This flag symbolises the tribal religion of Sarnaism, practised by Indigenous communities in the states of Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, and Chhattisgarh. At the heart of this tradition is the cult of the "sacred groves" known as sarna, a word etymologically linked to the name of the sal tree (Shorea robusta) that grows abundantly in the region. The shrine is the home of the village deity, to whom sacrifices are made several times a year.

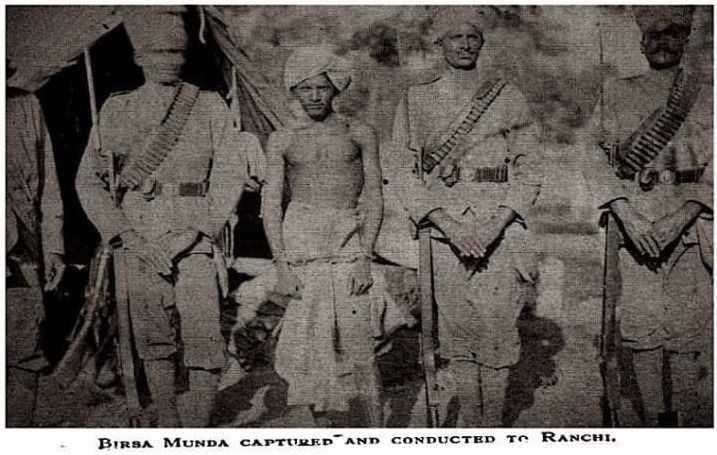

On the way, the taxi driver informs me that today, 15 November, is the birthday of the folk hero Birsa Munda, born into the Munda tribe in 1875. From an early age he condemned British oppression and Christian missionary conversions and urged his people to reclaim their land and ancestral rights.

The British, apprehensive about the growing popularity and strength of Birsa Munda and his bow-and-arrow warriors, arrested him on 3 March 1900 as he was sleeping with his troops in the forest. Taken to Ranchi jail, he died on 9 June 1900, aged twenty-five. Arriving near a roundabout that leads to the airport and bears the name of the famous freedom fighter, tribal dancers in close ranks hold hands in a circle to pay tribute to him.

In the waiting room, a last glance at the bust of Birsa Munda adorned with flowers, before taking off for southern India.

Previous articles:

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "An endangered heritage" — part 1

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Painting the walls for Sohrai" — part 2

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Painting the walls for Sohrai" — part 3

Jharkhand, Hazaribagh "Diwali at the Sanskriti Center" — part 4

Jharkhand, Sohrai festival " Painting aripan to welcome the cattle " — part 5