Kolam to celebrate Mattu Pongal — part 3

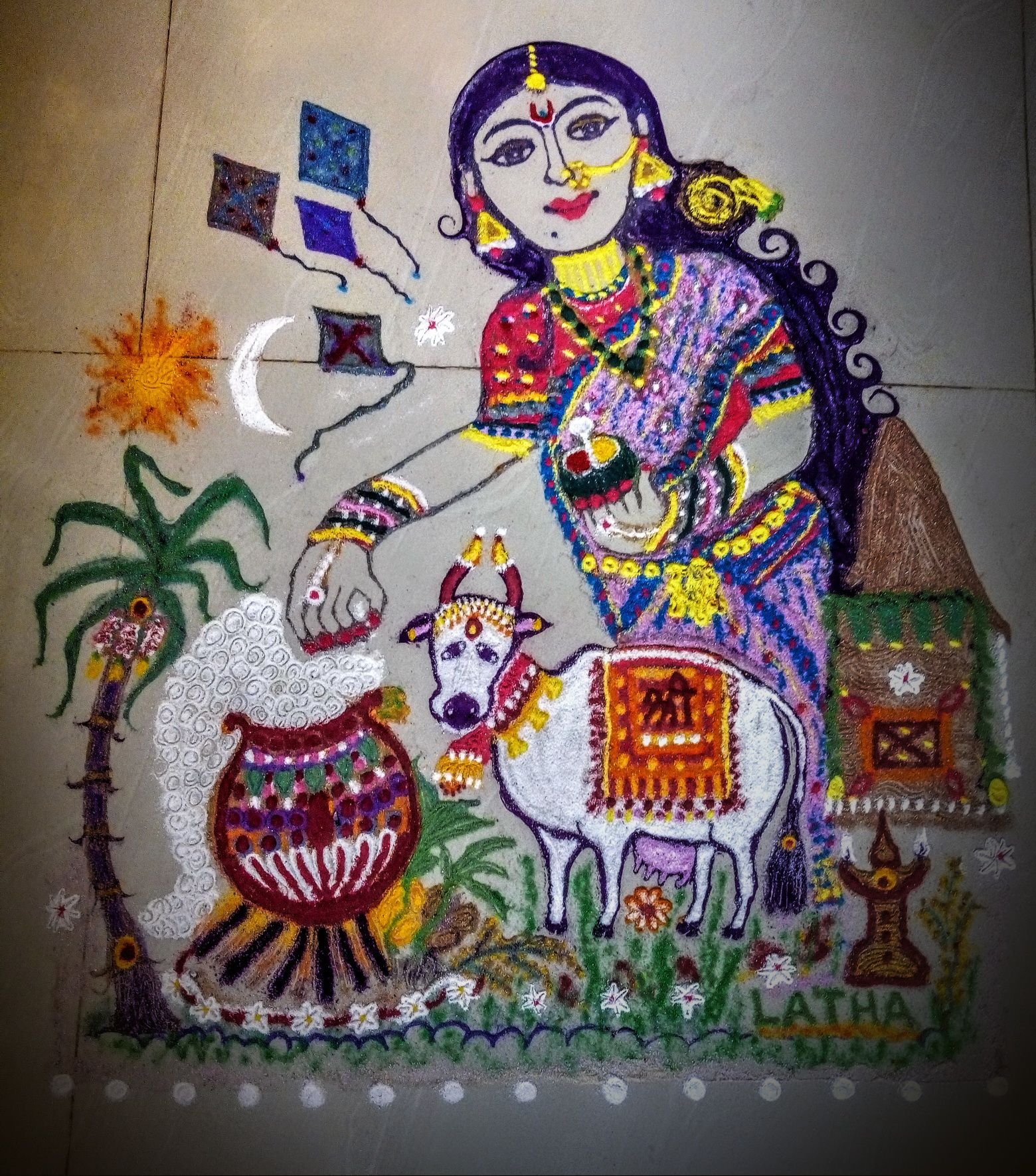

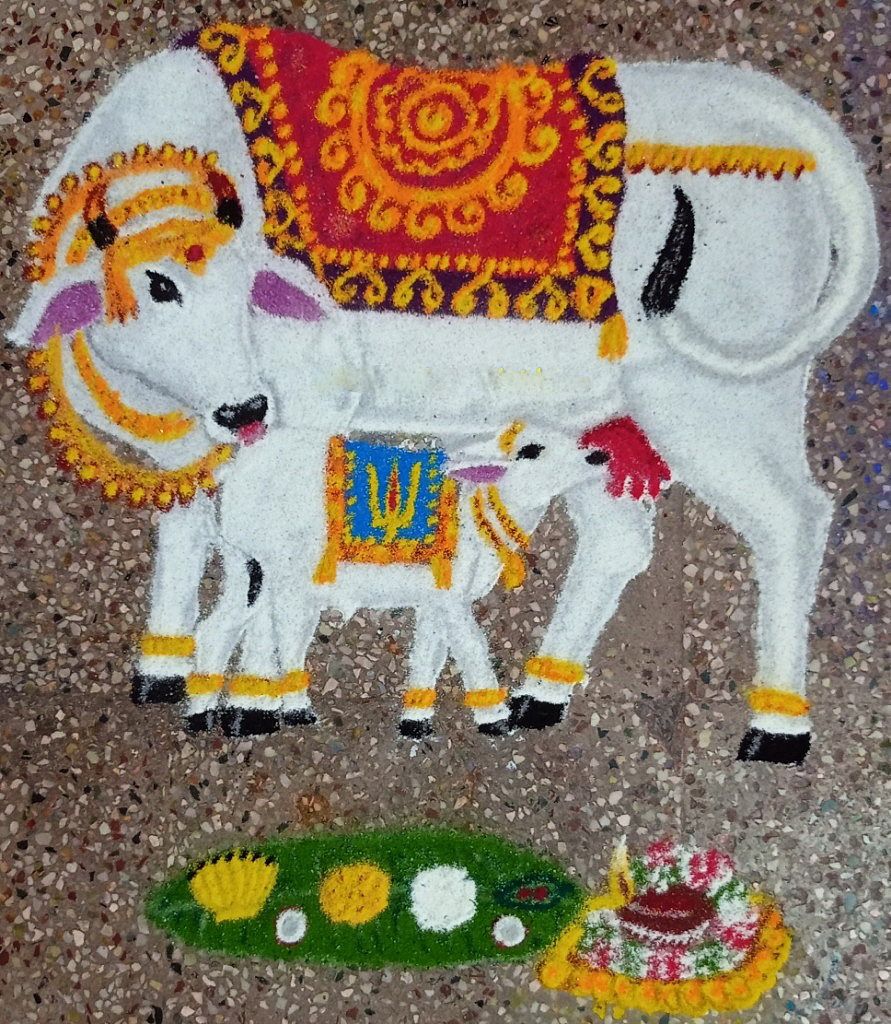

On Mattu Pongal day, the farmers buy their cows new bright halters, bells to adorn their hooves, brass cap horn ornaments, wreaths of fresh flowers, pom-pom garlands and multi-coloured beads to adorn their neck. They decorated the cow's coat in variations according to districts.

Gratitude to the farm animals and worship of the tools

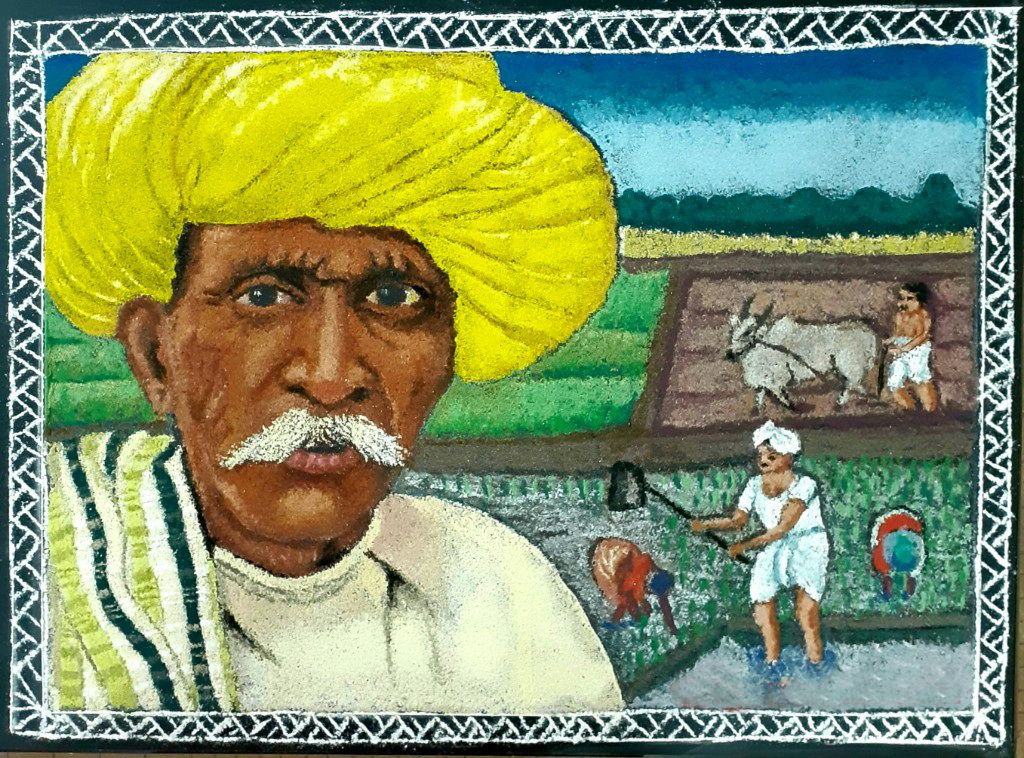

The third day of Pongal is dedicated to cattle worship and the word mattu means bull in Tamil; this reflects the importance of agriculture and animal husbandry in the regional economy. On this day, farmers worship their tools by anointing their ploughs and sickles with sandalwood paste or maavu (wet rice flour), and kunkumam (powder made by mixing turmeric with slaked lime, which turns the yellow into red colour).

The farmers buy their cows new bright halters, bells to adorn their hooves, brass cap horn ornaments, wreaths of fresh flowers, pom-pom garlands and multi-coloured beads to adorn their neck. They decorated the cow's coat in variations according to districts. Either the entire body is rubbed with turmeric paste or the coat is punctuated with coloured dots enhanced by a fine red line drawn from top of the head to the tail.

The horns are traditionally painted red and green but sometimes, they are embellished with gold or silver paint, or even colourful balloons. In recent years, tractors have become part of festivities and are honoured in the same way as their animal counterparts.

Once ready, the bovines are paraded in the streets to much fanfare. Their tinkling bells attract the villagers and onlookers pamper them with balls of sweet rice and escort them to the temple for blessings before heading for cattle races and bull fights.

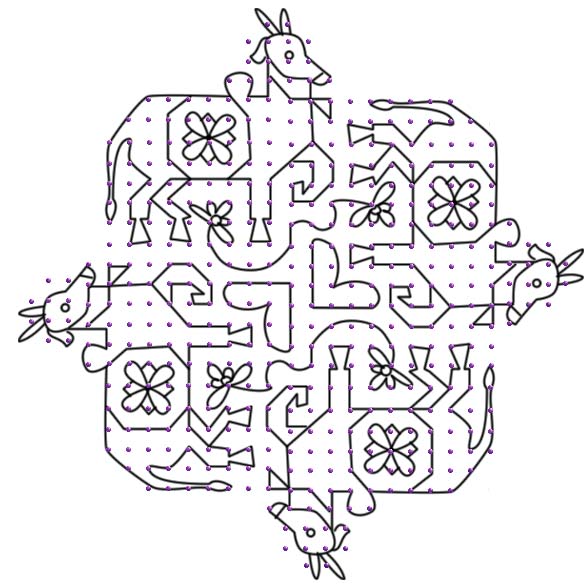

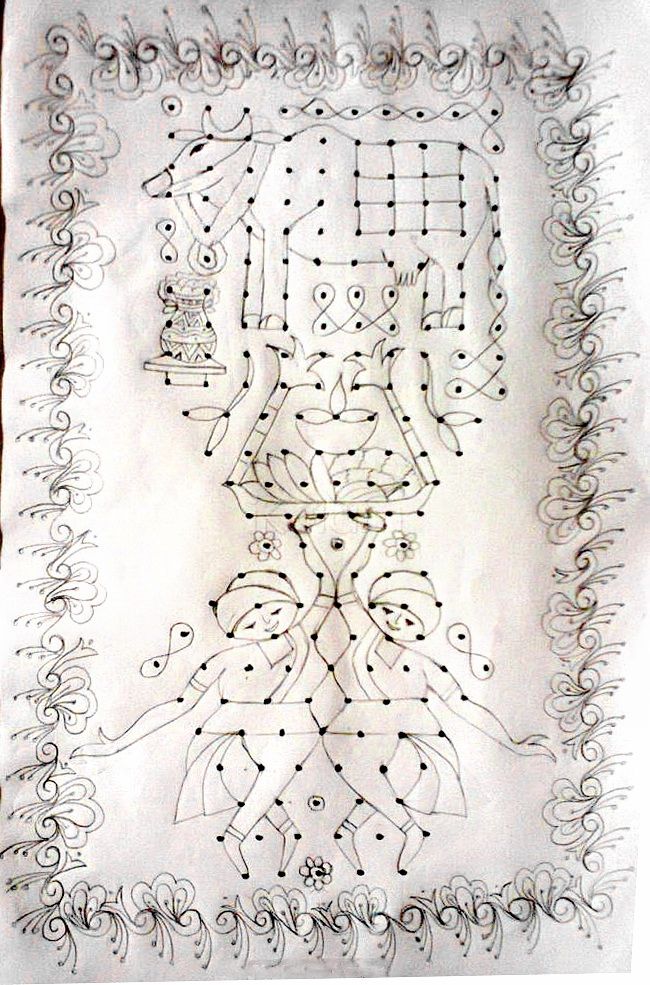

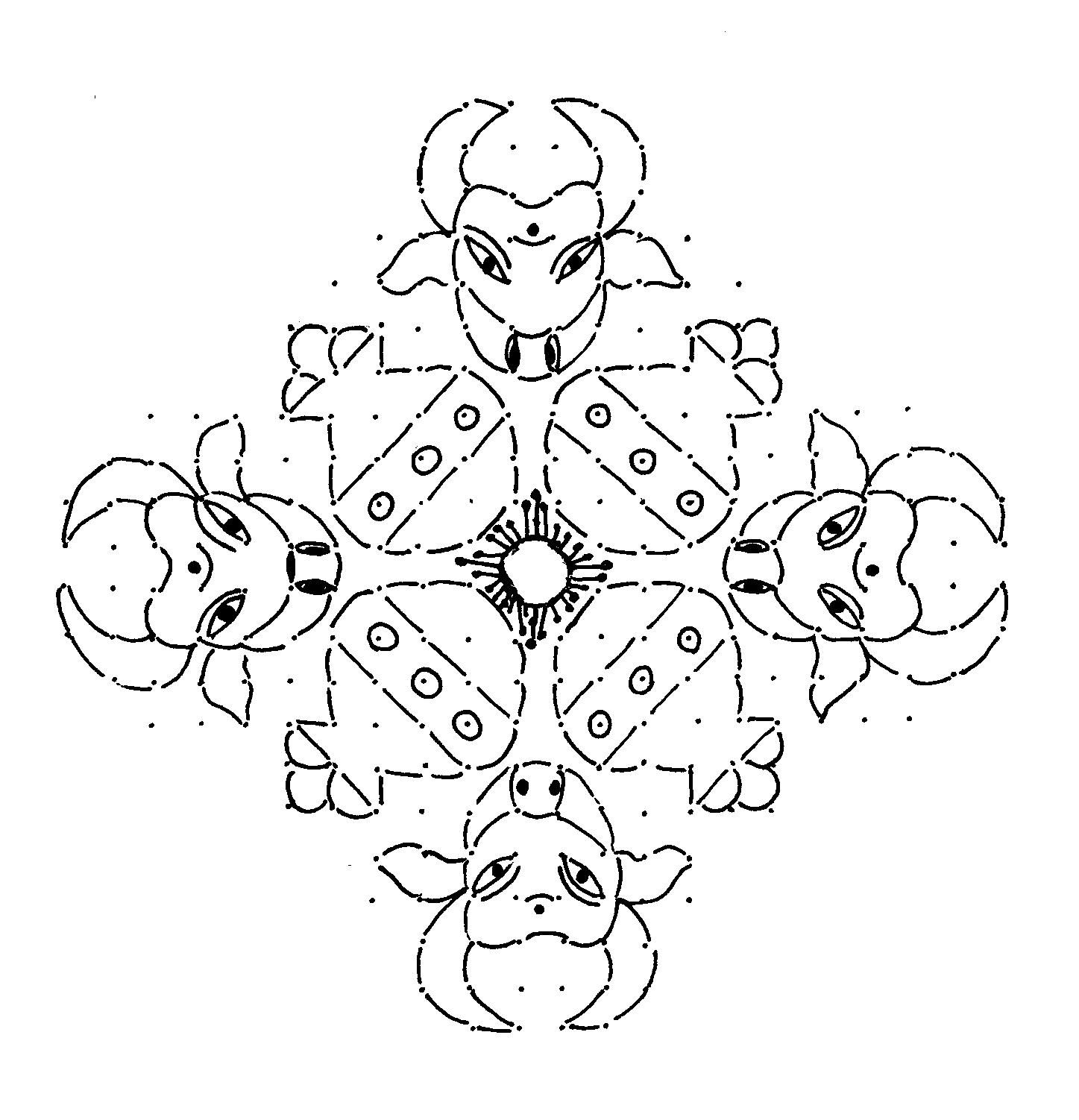

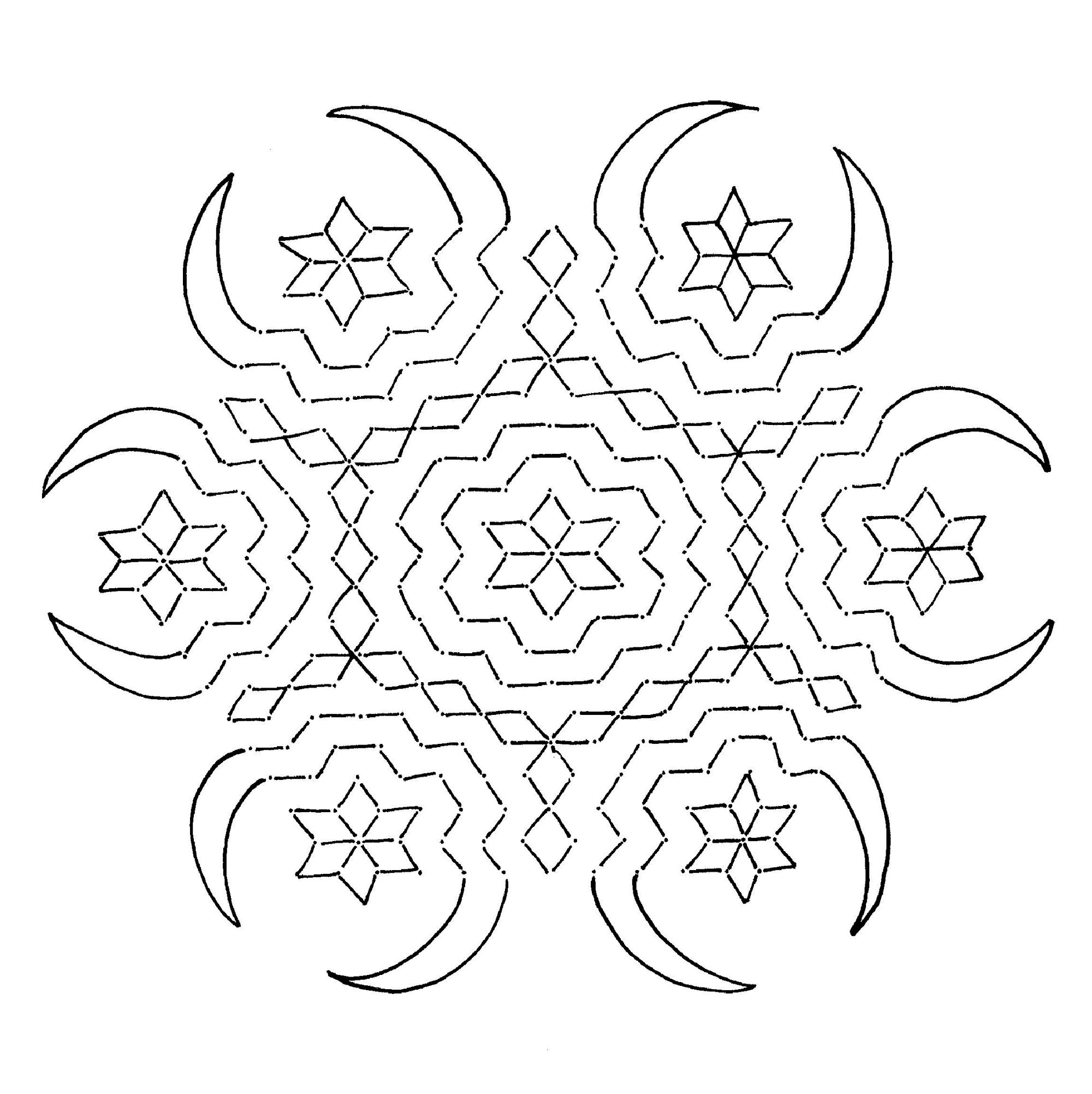

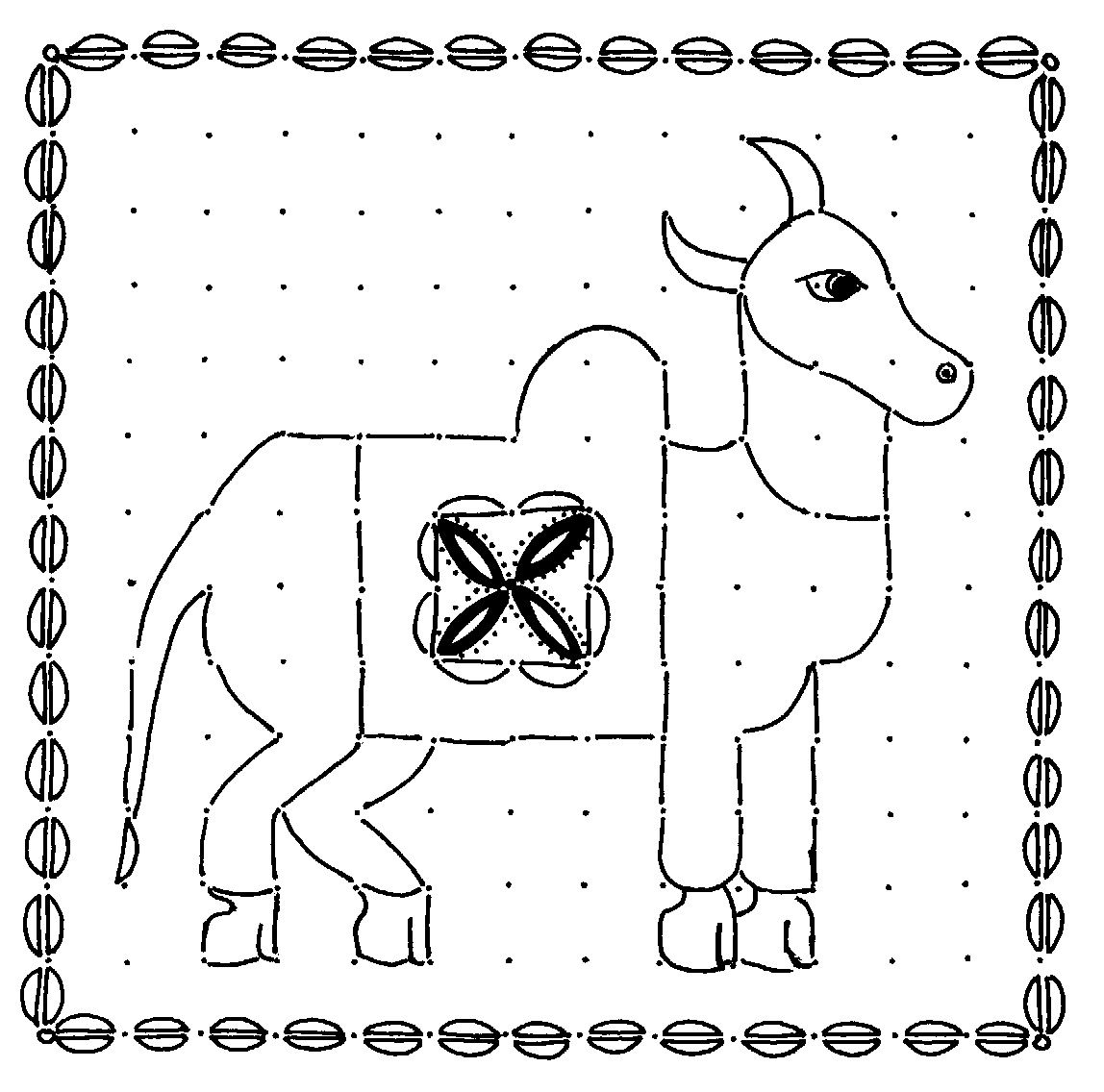

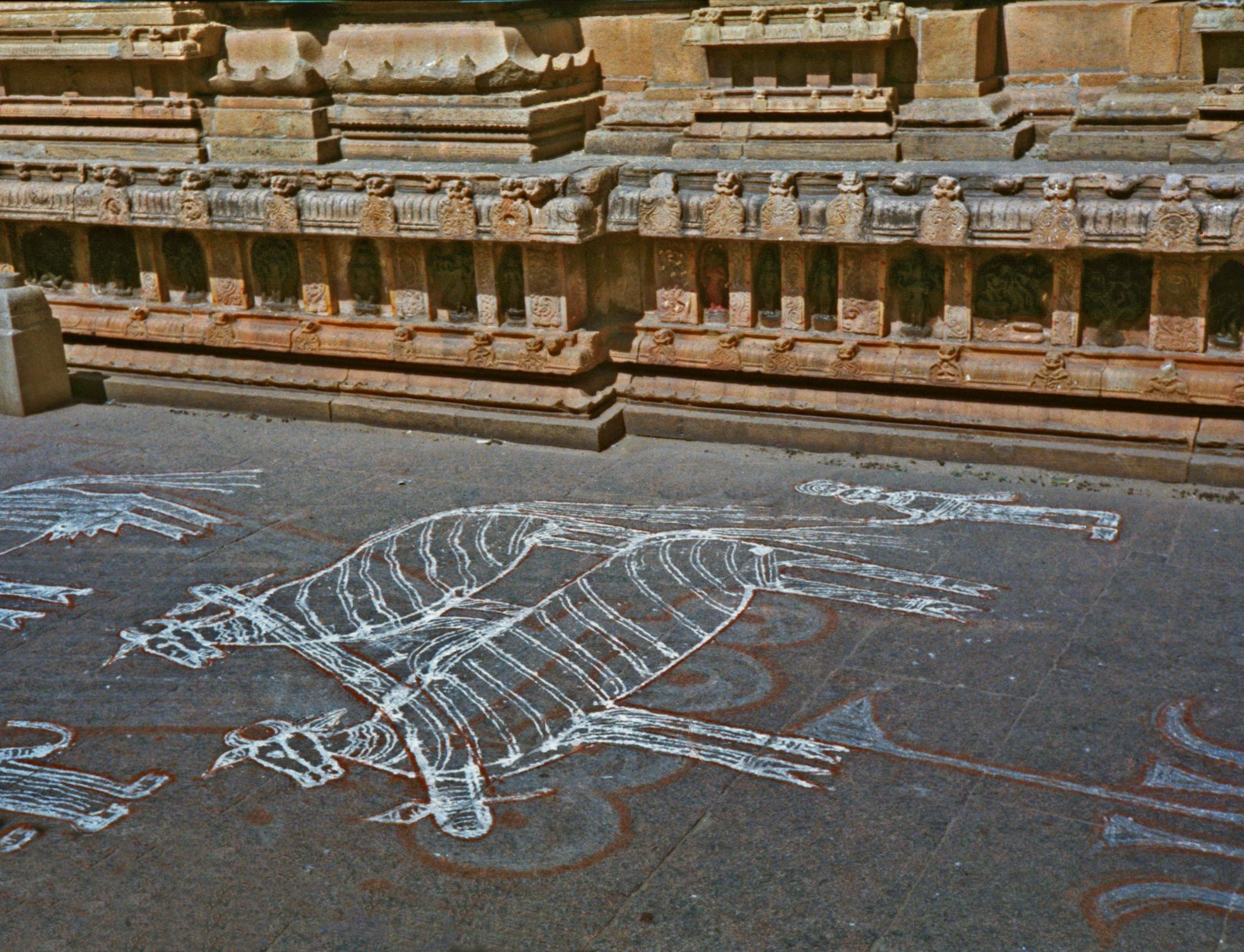

Naturally, the third day kolams depict cows or yoked bulls with or without the usual symbols of a rice pot, turmeric, and sugarcane stalks.

Mattu Pongal with Goundar farmers

More than any Pongal, this one was unique. It all started with the milkman of my Coimbatore friends. They knew that I had come to document Mattu Pongal festivities and my request was conveyed to their milkman who wholeheartedly accepted to welcome me in his farm. Reaching the village after one hour drive through the countryside, I met the rest of the family. The next day after my arrival, Surya Pongal went almost unnoticed; no kolam and no steaming earthen-ware cauldron of pongal was cooking. I was desperate as the previous year had been spent memorably with Surya Pongal at the home of another family in Chennai. Here on the farm, everyone seemed busy with some tasks. The young boys of the family spent almost the whole day scrubbing thoroughly the cowshed from floor to walls. Two farm workers kept bringing bricks inside and were arranging three hearths to cook what I presume would be the rice dishes. The lady of the house, sitting in the courtyard was tying up bundles of mango, sacred basil (Ocimum sanctum), and neem leaves along with avarai flowers (Senna auriculata) to hang them in front of the house with the aim of driving the evil eye away.

I was somehow upset as I had come to see kolam and they were none until I was called by the house master into the cowshed. There, I stand still, gawking at the sight of the most unusual three-dimensional kolam or should I say mandala created with cow dung. A perfect example of a padi kolam with gates in all four directions. I had never seen such a creation before; layer after layer, walls were erected until the enclosure was strong and high enough to receive water.

I was wondering why such a pond until I saw the householder placing a fine silver statue of a coiled snake topped by a kneeling baby Krishna holding butter. Then, I remembered the story of Sheshanâga, the king of all Nâgas resting on the primordial waters and forming the bed for Vishnu. Along the enclosure walls, incense sticks, elephants statues, and terracotta oil lamps found their place. Facing the central statue, two silver cows were looking up with reverence at the Lord of the universe and cowherd known as Gopal: literally meaning the cow protector. Behind the cow dung kolam, Sri Andal surrounded by cows was decorated with a homemade garland. Finally, all was ready for the homage to Krishna Gopala. All was still in the cowshed except for the blowing of the conch and the heavy breathing of the cows radiant in their turmeric coats. For a short moment, I had the feeling of being in a living nativity scene. The ritual ended with all the women ululating (kuravai) and the distribution of sweet rice balls to the cattle. Shortly after, the day culminated with a wonderful meal where family, friends, servants and farm workers were invited. After years, I always remembered this eco-friendly creation that I never saw again.

The grim reality of farmers

While I am writing this article, it is impossible not to refer briefly to the present situation of farmers in India. The grim reality is called drought, floods, and suicides. Indian agriculture like elsewhere in the world is experiencing increasingly erratic weather conditions due to climate change. Farmers are crumbling under heavy debt and non-existent profits due to crop failures. In 2020, the parliament passed three contested reforms bills that allows farmers to sell their products to buyers of their choice, rather than turning exclusively to government-controlled markets. The latter were created in 1950 to protect farmers from abuse and to provide them with a minimum support price (SMP) for certain commodities. Many smallholder farmers are attached to the SMP as an essential safety net and now feel threatened by market liberalization. They fear competition from larger farms, which may force them to sell their goods at cheaper price to large corporations. As I finish writing this article, I read that the Supreme Court has suspended the three laws against which the farmers had gone on strike for nearly three months. During the coming year, there will surely be many more twists and turns to the story.

If you feel like drawing, follow the dots and colour them.