Rajasthan mandana, "Jodhpur, the quest begins" — part 1

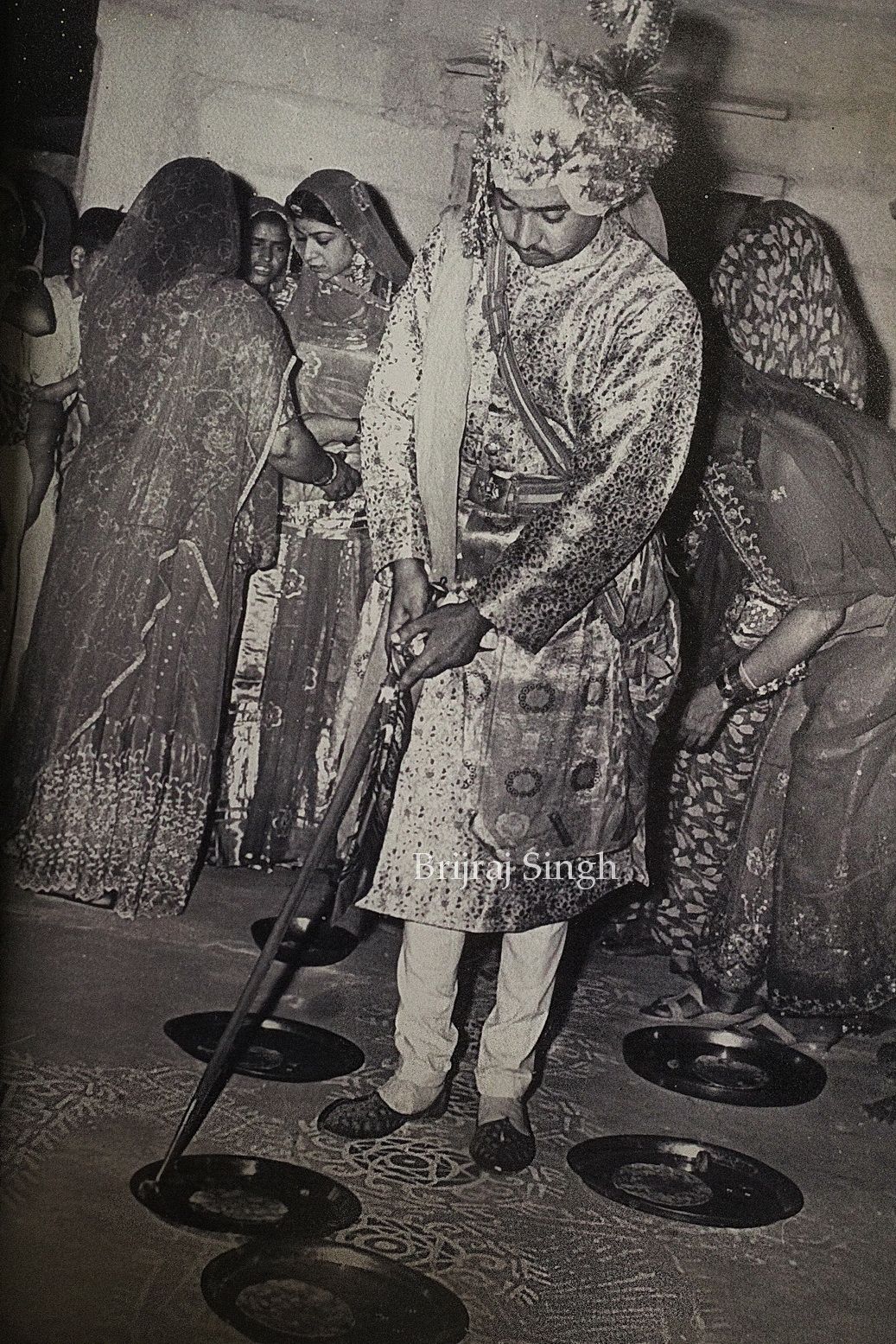

Holding a sword in both hands, the tip of the blade touches a metal plate placed on a floor painting made of several squares enhanced by a stylised flower in the center.

I have always imagined Rajasthan the "Land of kings" and India's largest state by area as a dry land, even as a desert region, where towering palaces and forts rise from every rocky peak. But geography tells a different story. The Aravalli Mountains divide the region into two different lands. The hilly landscapes, though modest in size, stop the south-eastern monsoons and leave the western part of Rajasthan without rainfall, while they abound on the eastern hillsides where cotton, flax, groundnuts, barley, wheat, and rice grow. By contrast, the mountains stop the winds weighed down by the sands of the Thar Desert.

When the quest starts at Ratan Vilas

I am far from my beloved southern lands, and it is in Jodhpur, the blue city, where my quest for the mandana, a colloquial term for floor drawings, begins. The doorways of the local houses seem austere compared to the Tamil thresholds adorned each morning with geometric allegories. Yet it is an elegant floor painting that greets me at the entrance to a royal house converted into a discreet luxury hotel.

And it is precisely here in this private residence that I became familiar with several local customs embodied by the hotelier couple. The walls of the corridor, which lead to the rooms, reveal slices of life of the entire lineage. Equestrian trophies and polo cups won by the great-grandfather are proudly arranged among portraits of ancestors and intimate family photographs. A black-and-white photograph just behind an oil lamp catches my attention, as it shows my host's father on his wedding day. He is seen standing in his best attire, surrounded by women adorned with translucent embroidered veils. Holding a sword in both hands, the tip of the blade touches a metal plate placed on a floor painting made up of several squares with a stylised flower in the centre. The faded photograph does not reveal much of the pattern, but the Rajput custom dictates that on the day of the wedding, the groom pushes aside metal plates to head towards the deity on the family altar. The bride-to-be, who follows him closely, must replace them one by one on each square. By this gesture, she conveys her capacity to be patient and discreet on all occasions within the household. He expresses his authority as head of the family and his ability to protect the household by the way he moves the dishes.

This is how the quest for mandana began. The painted diagrams, like their southern counterparts, remain witnesses to many Indian ceremonies and rites of passage. Birth, marriage, and other Hindu festivals are all reasons to draw. During a conversation with my hosts, they introduce me to two brothers who are farmers and occasional tour guides for hotel guests whom they drive to visit Bishnoi communities (Vaishnava farmers who are committed to the protection of nature and have a deep respect for trees). One of the brothers agrees to guide me and I leave the next day in the hope of discovering courtyards decorated with mandana that herald Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights.

Story to be followed...

Next articles:

Rajasthan mandana, "Preparing Diwali at Lakshmi's home" — part 2

Rajasthan mandana , "Bundi and nearby villages" — part 3

Rajasthan mandana, "Villages around Bundi" — part 4

Rajasthan mandana, "Adorning the floors for Diwali " — part 5

Rajasthan mandana, "Adorning the floors and the home for Diwali" — part 6