Rajasthan mandana, "Adorning the floors and the home for Diwali" — part 6

In Rajasthan floor paintings, most patterns of animate beings come to life on the vertical surfaces of the house, except for the symbolic representations of the footprints of Goddess Lakshmi, called paglya, and the hoof prints of the cow which are drawn on the floor inside and outside the house.

In Rajasthan floor paintings, most patterns of animate beings come to life on the vertical surfaces of the house, except for the symbolic representations of the footprints of Goddess Lakshmi, called paglya, and the hoof prints of the cow which are drawn on the floor inside and outside the house, and around the main mandana to welcome the Goddess and bless the family members.

Paglya, the divine feet

The veneration of the feet of gurus, deities, or elders is a deep-rooted gesture in Indian culture. In temples or at home, when there is no image of the deity, devotional foot-soles carved in wood, stone, plastic, or painted on paper can be found. The interior of the sole is either empty or filled with auspicious symbols pertaining to the deity; in the case of Vishnu, shankhu, chakra, gada, and lotus may find their place on the imprint. For Buddha, the carving of the soles often bear an engraved Dharmachakra or the wheel of Dharma, a symbol used in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. In some shrines, one may find used sandals of a revered guru or ascetics. When asked about this ritual, devotees often refers to a chapter of the Ramayana epic where Rama replaced by his brother Bharata, was sent into exile. Bharata, distressed by this decision, refused to be crowned in place of Rama and begged him to return to Ayodhya. Rama replied that he will return only after completing the fourteen years of exile. Bharata therefore returned to Ayodhya with his brother's sandals and placed them on the throne to signify his presence.

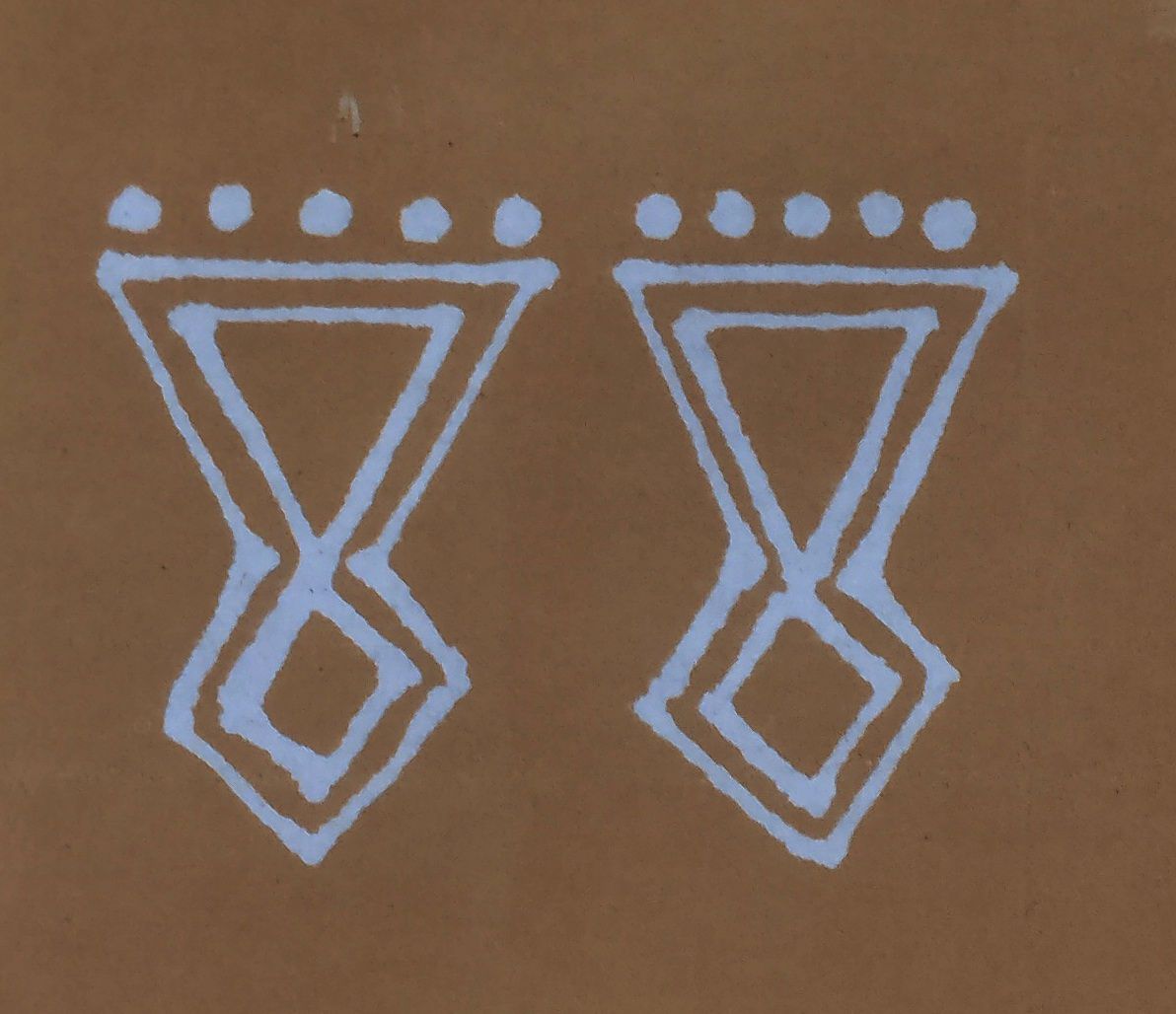

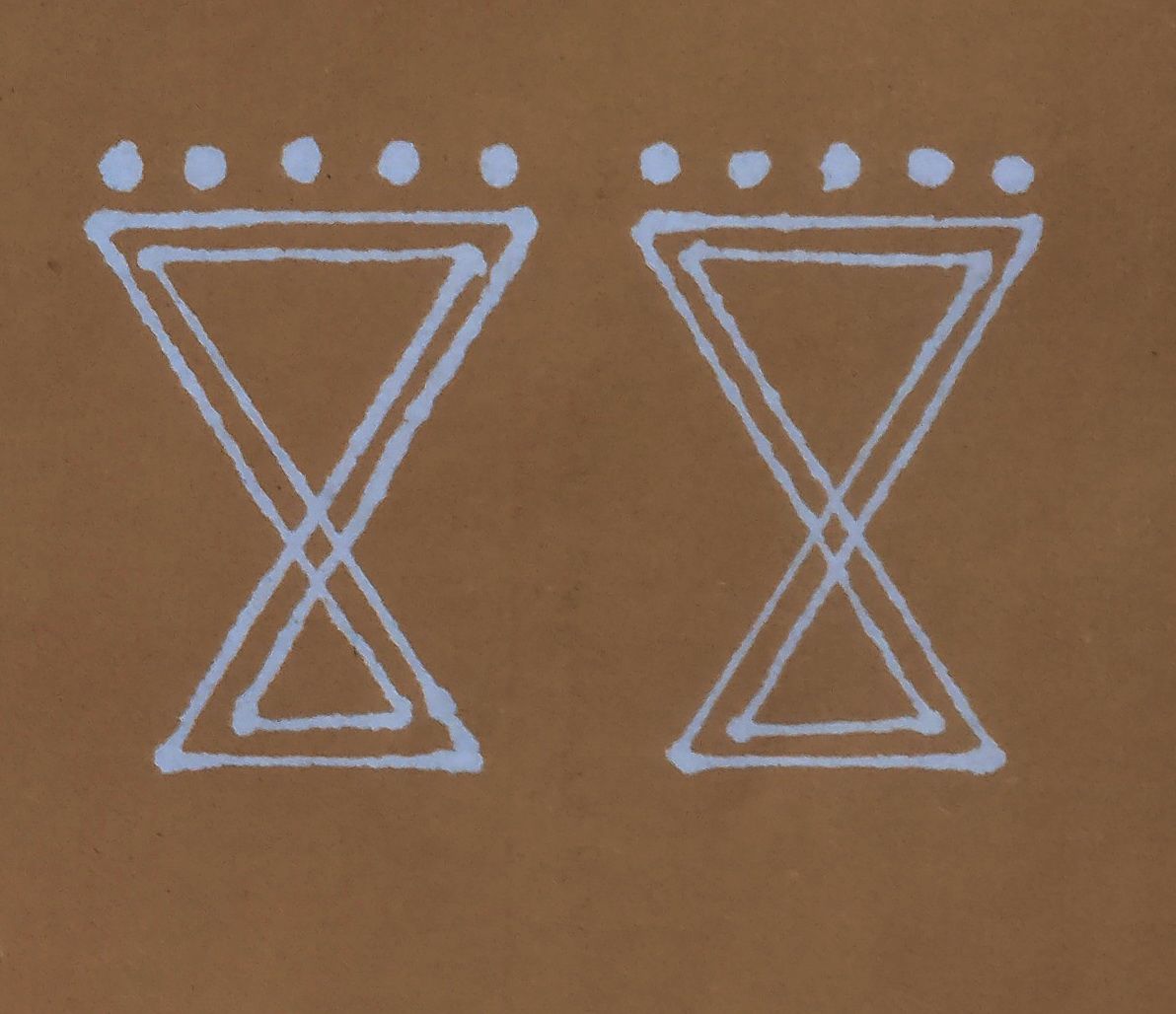

On some religious festivals, footprint paintings of Goddess Lakshmi for Diwali and Lord Krishna's birthday in South-India are drawn on the path to the house, on the doorstep, or inside the home leading to the domestic altar. Painted feet can be in the centre of a floor painting or are drawn as if in motion showing the path towards the house or to the family altar to invite prosperity. The most stylised paglya patterns look like the letter “Z” with a curved lower angle to signify the heel. Other paglya show a pair of two equilateral triangles connected by the summit. One of the two opposite triangles is of smaller size to display the back-foot and the other, with a wider base, and marked with five dots, symbolises the forefoot and the toes.

During Diwali, the simple footprint design becomes a masterpiece combining various geometric and braided elements, woven as in a basketry work. The footprints pattern also incorporates various motifs and symbols, as if to provide a protective case for the divine feet of the goddess, unless it is to exalt the greatness of Lakshmi, protector of the household.

Chotta mandana, the small mandana

Then, there are patterns like a myriad of satellites that fill the space around the central mandana or brighten up a corner of a previously banal room with their presence. There are also those that carry symbols like the ear millet (bharadi), cow hooves, birds, oil lamps, inkwells, or pens to symbolise annual accounts, scales and weights to increase trade. Other designs reflect hospitality in the form of sweets (laddu, jalebi), and a pot of vermilion (sindhur).

Decorations of mud, mirrors, and dung cakes

Other surprises delight the eyes when one enters a Meena house. What a joyful feeling to see these outstanding talents creating a wondrous and unique living environment. It is immersive, soulful, speaks of the roots as an agricultural community, bring in a magic touch transforming the cow dung cakes into a piece of art, sculpting shelves, storage units and embossing walls.

Walking through the alleys of a Meena village, my eyes are drawn to a floral garland created from cut-out mirrors and embedded in the door frame of one of the houses. Inside, facing the entrance, small circular mirrors and four compact discs for their reflective surface are encased in the wall and form a simple yet elegant frieze. This vision is reminiscent of the fairy-tale courtroom of the Amer Palace, which is studded with mirror cut-outs, or the Rabari embroidery in which circular mirrors have been inserted.

Two-dimensional mandana paintings that adorn the entire house, from floor to walls, sometimes take the appearance of embossed frescoes with inlays of mirrors, sequins, beads, and coloured glass, and tell stories of gods or scenes from daily life. There are also mandana filling designs that venture into three dimensional patterns to create shelves called kangura with niches for storing everyday items.

Cow dung is widely used as cooking fuel in many parts of India. Meena women collect dung from cows, bulls or buffaloes and mix it with straw to form a flat cake that is stuck to walls, tree trunks or sometimes even the ground to dry. To store the dung cakes during the rainy season, they build a container around the stacked dung cakes, with a thatched roof and a hole to take them out. The structure, called a piraunda, is also decorated with handmade designs.

Story to be followed...

Previous articles:

Rajasthan mandana, "Preparing Diwali at Lakshmi's home" — part 2

Rajasthan mandana , "Bundi and nearby villages" — part 3

Rajasthan mandana, "Villages around Bundi" — part 4

Rajasthan mandana, "Adorning the floors for Diwali " — part 5