Kerala Kalam, "Painting Vettakkorumakan, the hunter-god" — part 3

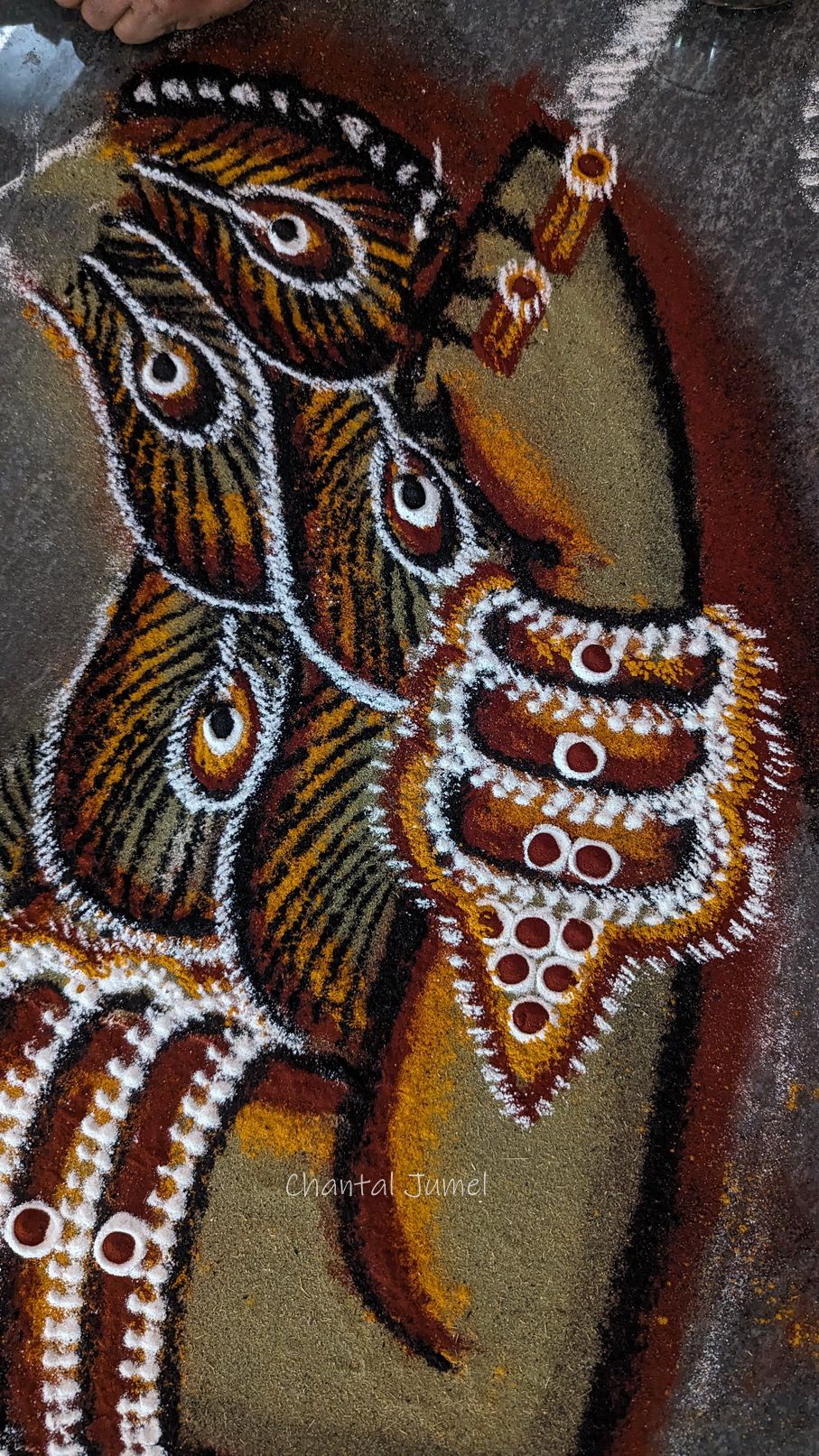

Like a jeweller, the painter creates fleeting ornaments that will adorn the sturdy neck, arms, wrists, and ankles of the sylvan deity. Another painter meticulously paints the peacock feather ocelli on either side of the deity, creating the illusion of a majestic mane.

Once again, the murmur of the night has given way to a nascent symphony of birdsong, timid at first, then growing in intensity. As the sky gradually brightens, the first rays of sunlight filter through the palm trees. Like the day before, I stroll leisurely through the lush green alleys, sipping a glass of chai while carefully observing the surrounding plants. The slightest breath of air carries sweet, intoxicating scents through the garden, creating a captivating olfactory palette. Among the branches of a tree, the jasmine curls up to reveal a fragrant, intimate embrace that is both delicate and enchanting. The Rangoon Creeper, a shrubby vine, displays its clusters of pale pink to purple flowers on the surrounding wall of the house.

Further down the wall, the Purple Wreath vine adds a touch of grace to my hosts' garden. The pale purple inflorescences unfurl in star-shaped cascades, attracting butterflies. Among the shrubs, a hibiscus flaunts scarlet petals, while a vibrant red Ixora unfolds its flowers in domed corymbs, which will be used tonight in the temple ritual to make the oracle's garland.

After a hearty breakfast, it was time to set off for the Sri Vettakarappan temple, located near a rice field below the village and estimated to be between 400 to 500 years old. In April 2022, the temple committee, including my host Ravishankar and his friend Nishanth Nottah, gathered to embark on the ambitious project of renovating and reconsecrating the sanctuary, which had suffered the ravages of time. The work was completed in 2023, and today, 14 December, marks the beginning of the first festival. It is a special occasion to participate in the two days of propitiatory rites dedicated to Vettakkorumakan and performed by the Kallatta Kuruppu community. They are part of a social class known as Ambalavasi, which literally means "Those who dwell in the sanctum." Their hereditary task is to paint images of deities with powder in public or private temples, as well as in the homes of individuals.

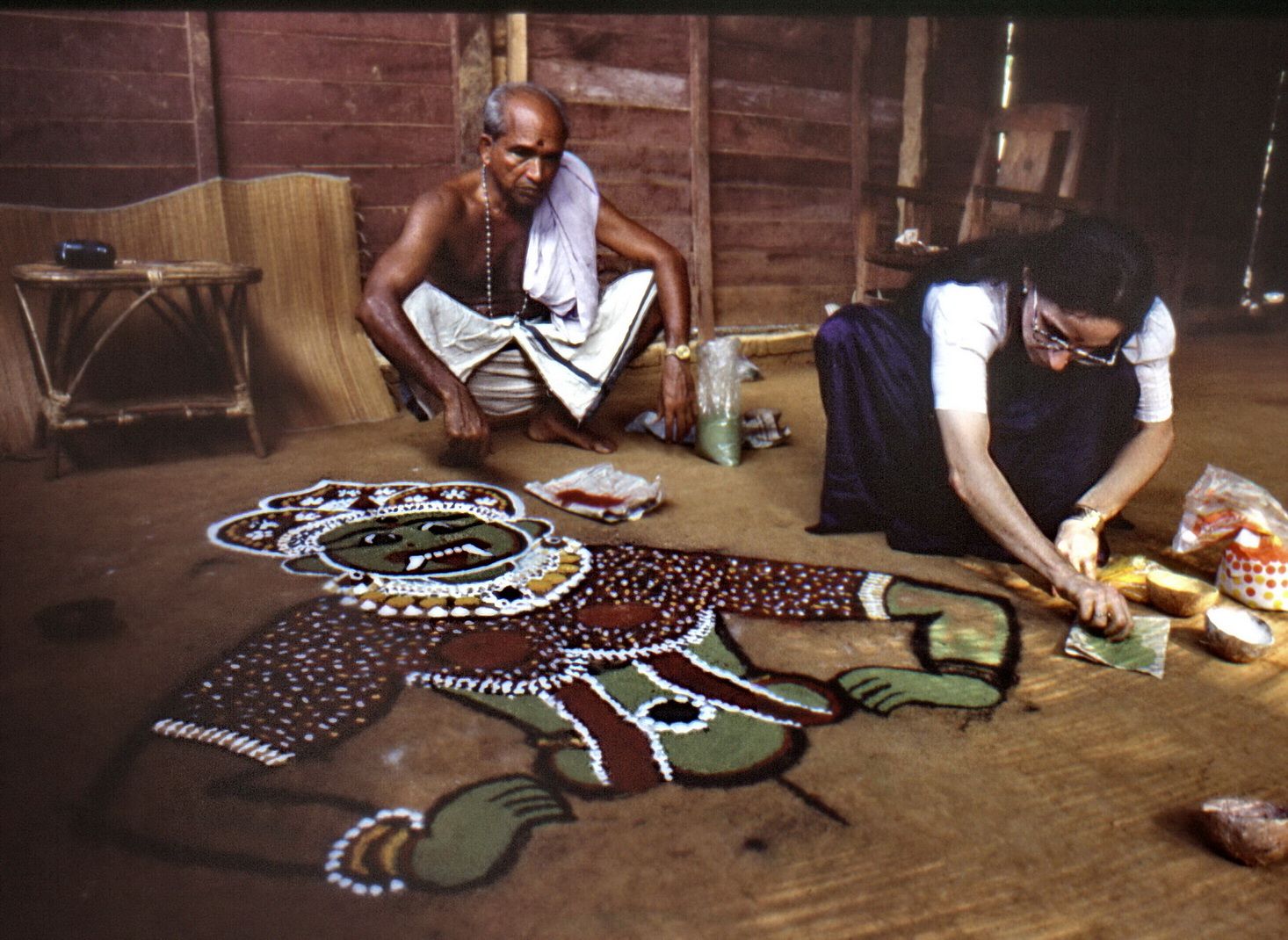

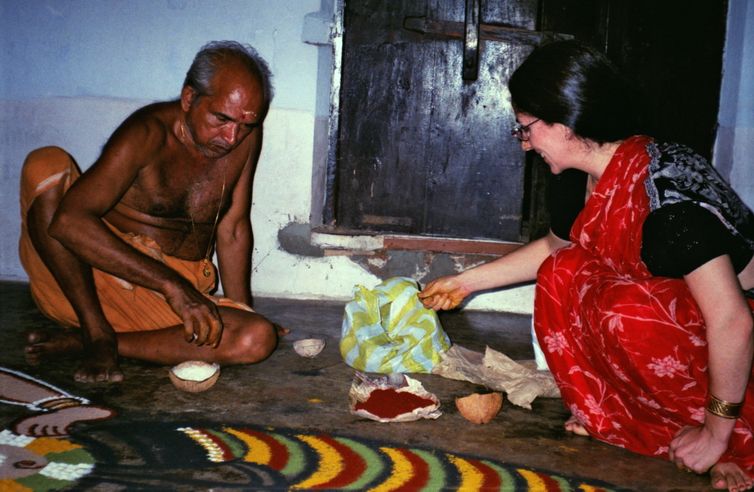

Thirty years ago, when I received a fellowship to document the traditions of ephemeral painting in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the Vijñana Kala Vedi Centre put me in touch with Sri Parameswara Kurup, a painter and musician attached to the Ambalapuzha temple (in Alappuzha district, southern Kerala) and also a member of the Kuruppu community. He came to the school several days a month to teach me drawing techniques, measurements and proportions, and the art of colour. He drew his entire repertoire for my research, illustrating several versions of a deity. Outside the classroom, I followed him as he performed in temples and private homes, taking notes, photographing, documenting the details of the various rituals, and at his request, sometimes helping him to apply the colours to the painting in progress.

Today, I am meeting artists from the same community, all from the Palghat (Palakkad) region. They are here to paint the deity Vettakkorumakan (വേട്ടക്കരുമകന്), whose cult is widespread in northern and central Kerala.

According to one legend, Vettakkorumakan is the son of the divine couple Shiva and Parvati. Disguised as a hunter and a huntress, they tested Prince Arjuna, who had come to the Himalayas to do penance and obtain the divine weapon Pashupatastra. After granting Arjuna the coveted weapon, the divine couple stayed in the forest for a while, where a son was born to them, named Vettakkorumakan, which literally means "Son of the hunt." The daring boy killed many demons, but his reckless use of the bow and arrow disturbed the gods and sages in their meditation. Overwhelmed by his mischief and recklessness, they turned to God Vishnu, who transformed himself into an old hunter, approached the boy, and offered him a dagger on the condition that he never let go of it. Vettakkorumakan respectfully circled the hunter, holding the bow and arrows in his left hand and the dagger in his right hand. Before Vettakkorumakan could finish his gesture, Vishnu disappeared. To keep his promise, Vettakkorumakan was forced to hold the short sword in his right hand, forever depriving him of the use of his bow and arrows.

Inside the temple, on a raised platform, I marvel at the floor painting taking shape. A kalam always begins with the drawing of a vertical line, the Brahmasutra, running east-west. On either side of this axis mundi, the officiant outlines the contours of the deity with rice powder. The height between the middle of the forehead and the chin (siras pada) serves as the standard measure for drawing the various parts of the body.

Gradually, a silhouette emerges as the painters swap brushes for fingers and traditional pigments for rice flour, turmeric powder, a mixture of turmeric and slaked lime, crushed acacia leaves, and burnt rice husks.

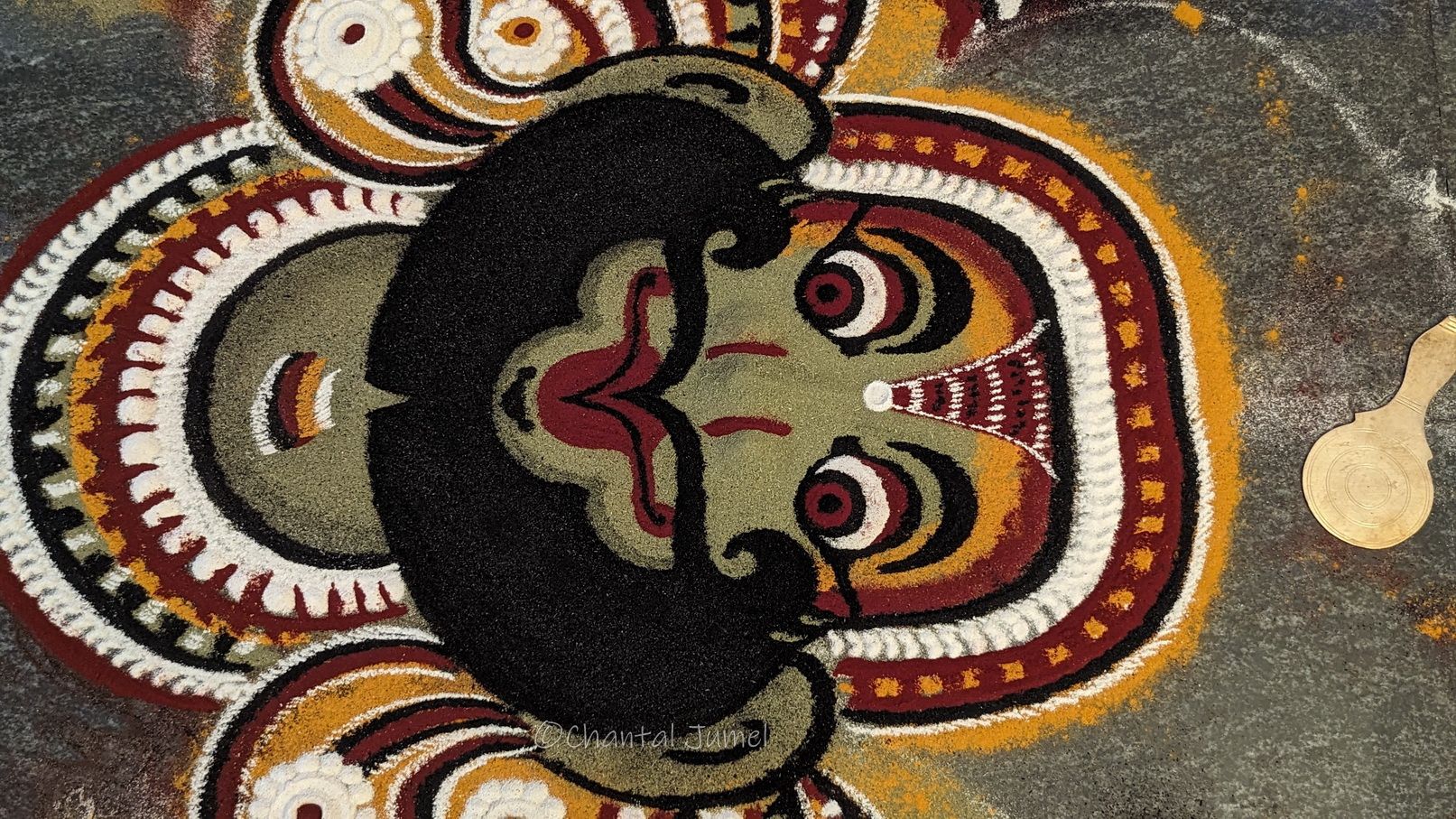

On contact with the hands, the powder comes to life, revealing unexpected landscapes. The thumb strokes the index finger or the hollow of the palm, sending the dust in a precise jet to create solid backgrounds. No sooner do two black and red piles emerge from the ground, than a bronze mirror flattens them into soft, firm curves. Thus transformed, they become the wide-open eyes of Vettakkorumakan, expressing courage and heroism.

Here and there, cones rise, immediately shaped by the flat of the hand or hollowed out by two or three fingers joined together. These strings of craters wait patiently for another colour to fill them.

Like a jeweller, the painter creates fleeting ornaments that will adorn the sturdy neck, arms, wrists, and ankles of the sylvan deity. Another painter meticulously paints the peacock feather ocelli on either side of the deity, creating the illusion of a majestic mane.

Around the mandorla (prabhavali) framing the deity, crossbars with zigzagging silhouettes punctuate the flat areas, accompanied by lines of juxtaposed colours.

His immaculate dagger contrasts with the richness of the fabric around his loins, known as virali pattu. This is an ikat fabric known as patola in the Gujarat region and was used in various rituals in Kerala.

The perfect mastery of the line and the relief effects created by numerous graphic techniques give a dimension that is both sculptural and pictorial, infusing a particular liveliness to the character depicted.

Story to be continued...

I dedicate the film Kalam Eluttu Pattu, Peindre et chanter le Kalam (Paint and sing the kalam) produced with the help of the CNRS, (National Centre for Scientific Research), Paris to Sri Parameswara Kurup (free viewing).

Previous article:

Kerala Kalam, "On my way to the village of Paruthipulli" — part 1