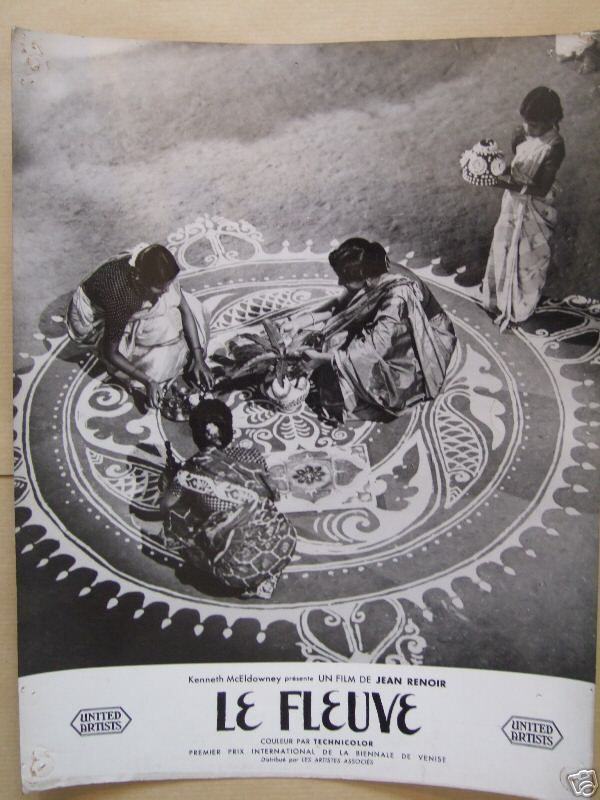

Bengal alpona, "The River by Jean Renoir"— part 1

The Bengal I have been dreaming of since I was a teenager is the Bengal of villages and the graphic creativity of the women, as in the opening scene of Jean Renoir's film "The River", shot in 1950 in Barrackpore near Kolkata.

My journey begins in Kolkata, at the home of Ruby Palchoudhuri, a true Francophile who has been a gallery owner, president of the Alliance Française, and ambassador of contemporary Bengali art in India and abroad. Today she works exclusively on the promotion of Bengali handicrafts, and it is through her that I will meet a young artist who will guide me through the villages.

The plane gradually begins its descent to Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta in the British Raj. I am apprehensive about my encounter with the mythical city, so many evocations of misery and decrepitude have shaped its image, year after year. I have in mind Fritz Lang and his diptych "The Bengal Tiger" and "The Indian Tomb". These two films, in the form of exotic and sensual peplums, mix images of everyday life in Kolkata with tableaux vivants in the manner of a mythological tale in which deceitful priests, power-hungry princes, a pure-hearted hero and a naïve and voluptuous sacred dancer follow one another. Other Westerners were introduced to Bengali literature by André Gide, who translated the poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore's "Gitanjali" in 1917. Still others discover the culture of Bengal through the films of Satyajit Ray, who examines and analyses the many facets of contemporary society and the superstitions of rural India. In 1998, when the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded, the West was also introduced to Amartya Sen and his work on the mechanisms of poverty.

But the Bengal I have been dreaming of since I was a teenager is the Bengal of villages and the graphic creativity of the women, as in the opening scene of Jean Renoir's film "The River", shot in 1950 in Barrackpore near Kolkata. Satyajit Ray, a great admirer of the French filmmaker, was part of the team and took care of the location scouting. The first images invite the audience to witness the creation of a floor painting called alpona while the narrator begins the story with the following words:

“In India to honour guests on special occasions women decorate the floors of their homes with rice flour and water, with this rangoli we welcome you to this motion picture.

In the manner of a documentary, Renoir filmed the festival of lights and a statue of Goddess Kali, the local market and scenes along the Ganges, and its boatmen. Since that film, Bengal has metamorphosed but no doubt the bucolic atmosphere captured on film is waiting for me somewhere in a village, because in India, the past and the present cohabit, the worlds overlap and merge. One often has the unique sensation of slipping from one century to another, or from one world to another. I look forward to discovering alpona like the one that amazed me when I watched "The River" on television with my parents. I will never forget the first few minutes of the film, when women were drawing the petals of a flower on the floor. Little did they know that they were also writing my destiny with the tips of their fingers.

Through social networks, I met two sisters, Malika Ganguly and Manjari Chakravarti, the daughters of one of the three women seen at the beginning of the film, and this how I was able to identify them. There is Shibani Chakravarti née Ghosh at the center who worked for the Red Cross and aunt Karuna Shaha on the left. The latter was a renowned artist in Kolkata. She was part of an all women group called “the group” in the 1960s, which the press renamed “Pancha Kanya”. On the left Khuki, the younger sister of filmmaker and documentarian Harisadhan Dasgupta born in Kolkata in 1923.

Next articles :

Bengal alpona, "Meeting with Kolkata" — part 2

Bengal alpona, "At Sumitra’s home"— part 3

Bengal alpona, "Poush Sankranti at Sumitra’s home" — part 4